Skywalker At Risk: Serial Storytelling and Brand Value

The contemporary entertainment industry – not only movies and television, but also prose fiction, comics, and gaming – sometimes finds itself confronting a crisis of identity, caught between competing interests. Creators often want to make art that speaks to their vision, regardless of commercial appeal. Investors usually want the greatest financial return possible, typically in the short term, regardless of artistic merit. The former reaches its peak at the Oscars, which are notorious for rewarding movies like The Artist that only people deeply immersed in the echochamber of self-indulgent Hollywood could want to see, much less enjoy. The latter is probably exemplified by Michael Bay’s body of work, particularly the Transformers movies, which contain essentially no storytelling or character depth but continue to excel at the box office. The tension between directors and studios, authors and publishing houses, can be difficult to reconcile, each side blaming the other when a project underperforms.

But the industry only exists at all because of a third interest: the paying audience. What do they want? Entertainment, and they have more access to more forms and venues of entertainment than ever before. Specifically, though, customers want to get what they believed they were paying for. With so many options to choose from, there is no need to waste money on something that doesn’t give you the entertainment experience you wanted. While sometimes a surprise twist or unexpected turn can be delightful, generally the customers want their expectations met – they want their entertainment dollars to be well spent on entertainment they enjoyed, not something that left them disappointed, even angry.

This dynamic poses special challenges for those segments of the entertainment industry built around serial storytelling. Like any other business that depends on loyalty from repeat customers not only for recurring purchases but also word of mouth, commercially successful serial storytelling requires building and maintaining goodwill with the fans. Once that goodwill is damaged – once the storytelling brand is tarnished – rehabilitating it can be difficult, if not impossible. Especially now that the audience can easily find and consume alternative entertainment, they have less incentive than ever to give a second chance to a brand that has burned them once before.

In the social media age, the challenge of serial storytelling is heightened. Word of mouth from ordinary customers is not local, but global. An incisive critique or compelling analysis can go viral, capturing the attention of those who otherwise would never have seen it. Coordinated trolling and automated bots can provide less reasoned negativity with a megaphone that gives it orders of magnitude more visibility than the underlying number of disgruntled individuals actually warrants. While trolls and bots may distort the perception of what actual customers believe – for example, the recent contrast between the Rotten Tomatoes rating for The Last Jedi compared to the movie’s CinemaScore – even distorted social media narratives can have an impact. When fans vote with their dollars, their choices reflect not only their personal preferences but also the influence of, and their reactions to, the interpersonal and social media discourse in the fandoms in which they participate.

In the social media age, the challenge of serial storytelling is heightened. Word of mouth from ordinary customers is not local, but global. An incisive critique or compelling analysis can go viral, capturing the attention of those who otherwise would never have seen it. Coordinated trolling and automated bots can provide less reasoned negativity with a megaphone that gives it orders of magnitude more visibility than the underlying number of disgruntled individuals actually warrants. While trolls and bots may distort the perception of what actual customers believe – for example, the recent contrast between the Rotten Tomatoes rating for The Last Jedi compared to the movie’s CinemaScore – even distorted social media narratives can have an impact. When fans vote with their dollars, their choices reflect not only their personal preferences but also the influence of, and their reactions to, the interpersonal and social media discourse in the fandoms in which they participate.

Since its rebirth in the 1990s, the Star Wars franchise has depended for its success on the fandom goodwill of its brand in compelling serial storytelling. Books and comics, videogames and roleplaying games, the Prequel Trilogy and The Clone Wars – all of it built upon the Original Trilogy, itself a serial story of three movies, to create the $4 billion brand value purchased by Disney in 2012. With plans to release at least one Star Wars movie per year for the foreseeable future, plus animated and live-action television shows and the ongoing release of ancillary storytelling in a variety of formats, Star Wars continues to tell tales – and seek financial success – as a serial storytelling brand.

The Fine Line Between Subversion and Implosion

Ever since The Empire Strikes Back, Star Wars has been associated with one of the most famous twists in all of contemporary storytelling. Nearly forty years removed, it is easy to forget that Vader’s claim to be Luke’s father was not immediately universally accepted as brilliant at the time. Some fans believed it; others insisted the villain was lying. Additional aspects of Empire were controversial at the time, too, including the tone, fairy tale structure, Han/Leia romance, and other ways the sequel departed from the original Star Wars. Likewise for Return of the Jedi, with its cuddly Ewoks defeating the Imperial army and Luke and Leia retconned into being siblings, among other developments. In hindsight, of course, the continued success of the franchise has papered over these fan disgruntlements – Star Wars obviously gained more fans than it lost from the addition of Empire and Jedi to the storyline.

Star Wars has subverted fan expectations at times, as well, though with greater risk and larger backlash. Much of the negative reaction to The Phantom Menace arose from a failure by Lucasfilm to manage fan expectations: the origin story of Darth Vader did not, for many fans, imply a film about a teenage girl and ten-year-old boy starring in tale centered on an interplanetary trade dispute and space Nascar. Again, hindsight shows that the public narrative was distorted. While a small number of Original Trilogy fanboys warped their sense of disappointment into betrayal and rage, and used their hyperbole and entitlement to gain disproportionate attention in the online and news media discourse about the film, Episode I was not widely despised at the time – and as the children who grew up on the Prequels have matured into their own voices in the fandom, it is eminently clear that Star Wars gained far more fans from the Prequels than it lost.

Star Wars has subverted fan expectations at times, as well, though with greater risk and larger backlash. Much of the negative reaction to The Phantom Menace arose from a failure by Lucasfilm to manage fan expectations: the origin story of Darth Vader did not, for many fans, imply a film about a teenage girl and ten-year-old boy starring in tale centered on an interplanetary trade dispute and space Nascar. Again, hindsight shows that the public narrative was distorted. While a small number of Original Trilogy fanboys warped their sense of disappointment into betrayal and rage, and used their hyperbole and entitlement to gain disproportionate attention in the online and news media discourse about the film, Episode I was not widely despised at the time – and as the children who grew up on the Prequels have matured into their own voices in the fandom, it is eminently clear that Star Wars gained far more fans from the Prequels than it lost.

Yet the possibility of a tipping point remains. Entertainment brands that once dominated their sphere can collapse if their fans walk away. Serial stories can overstay their welcome; for every Supernatural or Grey’s Anatomy that sustains its fan enthusiasm for years, there are many more The X-Files, Heroes, or Castle that go out with a sad whimper unworthy of their heights. One bad storytelling choice can doom a series, shedding audience that never returns, like Lois & Clark or Sleepy Hollow. Even decades-old prominent brands are not immune. The box office returns for the recent DC Comics films significantly underperformed their potential by reference both to past movies with those iconic characters and to their Marvel Cinematic Universe contemporaries. A decade ago it would have seemed laughable to suggest that the Guardians of the Galaxy would star in one movie, much less two, or Thor in a third – and yet both earned more than the much-anticipated Justice League superhero team-up by enormous margins.

Outside the films, the track record of Star Wars storytelling demonstrates that the risk of alienating fans from the brand is real. As FANgirl documented and analyzed extensively over our first year of publication, the flagship novels of the Star Wars Expanded Universe storyline (later relabeled as Legends after the Disney acquisition and reboot) experienced a precipitous decline when cascading bad storytelling choices pushed fans away in droves. The ambitious nineteen-book series The New Jedi Order (1999-2003) necessarily included some controversial storytelling choices, such as the deaths of Chewbacca and Anakin Solo, but managed to retain and sustain a vibrant fandom. Each successive storyline, though – from the Dark Nest trilogy (2005) to the Legacy of the Force (2006-2008) and Fate of the Jedi (2009-2011) nine-book series and culminating in Crucible (2013) – compounded the errors of the previous: new generation characters kept in the shadow of the legacy characters; the characterization and values of the legacy characters undermined with portrayals of them as morally dubious individuals rather than flawed human beings; the female leads attached at the hip to their husbands or lovers, and their story arcs sidelined in favor of showcasing their male counterparts; reliance on power creep rather than emotional stakes to drive the challenges faced by the protagonists. Karen Traviss in particular subverted the norms of the franchise, crafting stories premised on the notion that the Jedi and the Skywalkers were dangerously overpowered menaces and moral hypocrites whose deeds had done more harm than good to the galaxy. Another writer, Troy Denning, was responsible for nearly half (10 of 22) of those books, and interviews and other materials at the time confirmed that his vision and values shaped much of what occurred in the flagship series’ storylines and characterizations.

Outside the films, the track record of Star Wars storytelling demonstrates that the risk of alienating fans from the brand is real. As FANgirl documented and analyzed extensively over our first year of publication, the flagship novels of the Star Wars Expanded Universe storyline (later relabeled as Legends after the Disney acquisition and reboot) experienced a precipitous decline when cascading bad storytelling choices pushed fans away in droves. The ambitious nineteen-book series The New Jedi Order (1999-2003) necessarily included some controversial storytelling choices, such as the deaths of Chewbacca and Anakin Solo, but managed to retain and sustain a vibrant fandom. Each successive storyline, though – from the Dark Nest trilogy (2005) to the Legacy of the Force (2006-2008) and Fate of the Jedi (2009-2011) nine-book series and culminating in Crucible (2013) – compounded the errors of the previous: new generation characters kept in the shadow of the legacy characters; the characterization and values of the legacy characters undermined with portrayals of them as morally dubious individuals rather than flawed human beings; the female leads attached at the hip to their husbands or lovers, and their story arcs sidelined in favor of showcasing their male counterparts; reliance on power creep rather than emotional stakes to drive the challenges faced by the protagonists. Karen Traviss in particular subverted the norms of the franchise, crafting stories premised on the notion that the Jedi and the Skywalkers were dangerously overpowered menaces and moral hypocrites whose deeds had done more harm than good to the galaxy. Another writer, Troy Denning, was responsible for nearly half (10 of 22) of those books, and interviews and other materials at the time confirmed that his vision and values shaped much of what occurred in the flagship series’ storylines and characterizations.

The implosion of the Expanded Universe flagship novel line is a cautionary tale for Lucasfilm in the new era of Star Wars. If the novels had sold like Harry Potter or The Hunger Games, they would have become the new movies. Instead, their sales trajectories compelled the contrary decision. Once the tipping point is passed – once fans vote with their dollars by walking away – it is nearly impossible to escape that event horizon. After it occurred, the reboot of post-Return of the Jedi storytelling was necessary and inevitable. The future of the franchise depended on new creators restoring the franchise to its first principles and core values, giving lapsed fans a reason to return and potential new fans a reason to set aside the existing negative word of mouth and find hope in the possibility of starting fresh.

Some of the storytelling choices made in the new era show that the risk is not yet gone. The portrayal of the Han/Leia relationship in The Force Awakens created disappointment and apprehension in many longtime fans. So too did the backstory for Luke that unfolded in The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi. While The Last Jedi may be deemed only mildly underperforming on its own terms, it ought to concern Lucasfilm that Episode VIII’s box office performance is more comparable to Rogue One – a standalone film with unfamiliar characters – than Episode VII, its flagship predecessor. Fans of Rey, too, have reason to worry that the films will not deliver on her potential.

Some of the storytelling choices made in the new era show that the risk is not yet gone. The portrayal of the Han/Leia relationship in The Force Awakens created disappointment and apprehension in many longtime fans. So too did the backstory for Luke that unfolded in The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi. While The Last Jedi may be deemed only mildly underperforming on its own terms, it ought to concern Lucasfilm that Episode VIII’s box office performance is more comparable to Rogue One – a standalone film with unfamiliar characters – than Episode VII, its flagship predecessor. Fans of Rey, too, have reason to worry that the films will not deliver on her potential.

And like the Expanded Universe period, Lucasfilm is now positioned to let two men, J.J. Abrams and Rian Johnson, exert creative control over six of eight films in the new era, including all three movies in the flagship Skywalker family saga. Other men on the Story Group, relied upon for their expertise in Star Wars lore and Legends, were the same people in the room when the Expanded Universe imploded. Prior to its release, Johnson and various Lucasfilm executives spoke proudly about how The Last Jedi would subvert fan expectations; even the trailer emphasized that “this is not going to go the way you think.” If those storytelling decisions and characterization decisions do not sufficiently align with what the audience wants to purchase, however, Star Wars could quickly find itself deep in another storytelling – and financial – hole.

The Theme of Balance and the Skywalker Legacy

From the beginning, Star Wars has been a story about balance: Rebellion and Empire, light and dark, nature and technology, Jedi and Sith, selflessness and selfishness.

As the central characters in the Original and Prequel Trilogies, the Skywalkers have represented this theme within their family soap opera saga. Luke in the light and Vader in the dark. Anakin’s selfish possessiveness and Padmé’s selfless commitment to duty. In the Legends flagship storyline the next generation continued the theme, with Jacen’s tragic fall balanced by Jaina’s Jedi heroism.

In choosing to tell a Sequel Trilogy about a “nobody” Jedi hero and a single familial heir, however, the franchise has abandoned the balance in the Skywalker saga. Across the generations, the family has seen Anakin’s failure-turned-villainy balanced by Padmé’s heroism; Luke’s failure by foregoing his duty contrasted with Leia’s persistence in the good fight; and the darkness in Kylo Ren balanced by… no one. If Rey is not a Skywalker heir, her presence in the story cannot count toward balance in the Skywalker family saga. The third generation has no heroism, only villainy.

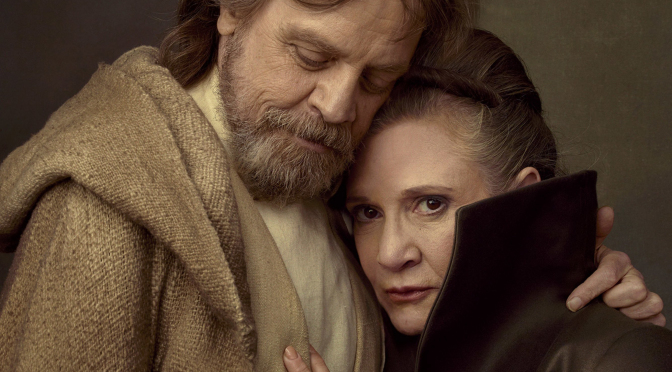

The imbalance appears likely to continue after the revelations of The Last Jedi. Given the completion of his Villain’s Journey, Kylo Ren has rejected the opportunity of redemption in favor of his commitment to the dark side. But that, by itself, would not have doomed the Skywalkers to a dark legacy: the film also establishes the path to redemption for the family. Luke has learned his final lesson in fulfilling his Wizard’s Journey, transcending past his failures with Ben Solo and the Jedi Order to stand as a spark of hope for heroes in the galaxy. Leia, too, is poised to undertake a Wizard’s Journey, finally accepting the power of the Force within her to become a Jedi and help Rey rebuild the Jedi Order. If Carrie Fisher’s untimely death leads to the removal of Leia from Episode IX’s story, however, then the Skywalker balance will never be found: Luke’s spark will never be fulfilled by Leia; Leia will never attain her destiny; and the fate of Kylo Ren and the Jedi Order will be decided from outside the family. Without Leia in the story and without Rey as a family member, the balance is lost and the Skywalkers end in darkness.

The imbalance appears likely to continue after the revelations of The Last Jedi. Given the completion of his Villain’s Journey, Kylo Ren has rejected the opportunity of redemption in favor of his commitment to the dark side. But that, by itself, would not have doomed the Skywalkers to a dark legacy: the film also establishes the path to redemption for the family. Luke has learned his final lesson in fulfilling his Wizard’s Journey, transcending past his failures with Ben Solo and the Jedi Order to stand as a spark of hope for heroes in the galaxy. Leia, too, is poised to undertake a Wizard’s Journey, finally accepting the power of the Force within her to become a Jedi and help Rey rebuild the Jedi Order. If Carrie Fisher’s untimely death leads to the removal of Leia from Episode IX’s story, however, then the Skywalker balance will never be found: Luke’s spark will never be fulfilled by Leia; Leia will never attain her destiny; and the fate of Kylo Ren and the Jedi Order will be decided from outside the family. Without Leia in the story and without Rey as a family member, the balance is lost and the Skywalkers end in darkness.

If this is how the story of the Sequel Trilogy unfolds – with a Rey Random hero and the Skywalkers as an epic failure in the galaxy’s history – it makes perfect sense why George Lucas repeatedly has remarked that Lucasfilm is not using his ideas for what the Sequel Trilogy might have been. Though most of the contents of his story ideas and Michael Arndt’s development of them remain secret, it seems highly unlikely he pitched anything like that.

It seem unlikely, too, that a dark end to the Skywalker story is what Disney had in mind when it launched the Sequel Trilogy after acquiring Lucasfilm in 2012. Investors do not expect references to “the iconic Skywalker family saga” to result in stories that turn those characters into failures and villains without counterweights from triumph and heroism. The Skywalker Vineyards wine sold at the Star Wars Launch Bay in the Disney parks on both coasts is not nearly as tempting when it represents an awful family that wrecked the galaxy.

The Star Wars franchise has been down this road before. Fans did not like the subversion of the Skywalker legacy in the Legends tales, and a repetition is unlikely to be better received. The notion of a Rey Random heroine has evoked positive response in some quarters of the fandom, and perhaps those who find enjoyment in that message will ultimately outnumber those who are alienated by the subversion of the Skywalkers. One important lesson of the Expanded Universe implosion, though, is that in the aggregate female fans tend to vote with their dollars and walk away from the franchise quietly; it is usually the outraged fanboys who stoke vocal controversy and insist on having their voices publicly acknowledged. Lucasfilm is taking a big risk with many of its longtime fans by subverting the Skywalker legacy – and if they are quietly starting to walk away again, the truth of the fandom’s reaction to the Sequel Trilogy’s story may not be apparent until the damage to the brand’s goodwill is already done.

.

Related Links: Legends / Expanded Universe

- Fangirl Speaks Up: Star Wars Books and Me – Caught in a Bad Romance (Feb. 2011)

- Fangirl Speaks Up: The Missing Demographic (Feb. 2011)

- Fangirl Speaks Up: Reenergizing the EU Novels (Mar. 2011)

- Luke Skywalker Must Die (May 2011)

- Can Luke Skywalker Avoid Character Apocalypse? Follow-up to Luke Skywalker Must Die (June 2011)

- Fate of the Jedi Weekend Update (June 2011)

- Seeking Strong Female Heroine: Jaina Solo in The New Jedi Order (June 2011)

- Ben Skywalker’s Ascension into Domestic Violence – Why the Fate of the Jedi Hurts So Much (Aug. 2011)

- When Equal Isn’t Equal – Troy Denning’s Role in the Star Wars EU (Aug. 2011)

- Seeking Strong Female Heroine: Mara Jade Skywalker in the Star Wars EU (Oct. 2011)

- Are These the Changes Fans Are Looking For? SDCC Star Wars Books Announcements (July 2012)

- Passing the Torch [Crucible novel] (July 2013)

- Making the Commitment to Relatable Storytelling (Sep. 2013)

- The Potential Energy of Major Star Wars Events (Apr. 2014)

- Franchises, Fandom and Protecting the Brand Message (Aug. 2014)

Related Links: Sequel Trilogy

- Resurrecting Legends: Is the Star Wars Reboot Gendered?

- Rey At Risk: Keeping Lucasfilm Accountable to Her Potential

- Leia Organa: Leader of the New Jedi Order

- The Problems With Rey Random: A Storytelling Analysis

- Leia At Risk Revisited: The Stakes After The Last Jedi

- The Last Jedi and the Hero’s Journey – Part Four: Kylo Ren and the Villain’s Journey

~

~