Telling Hi(stories) using Gaming: An Interview with Mariaelena DiBenigno and Khanh Vo

by Priya Chhaya

What does Assassins Creed have to do with teaching history? A few months ago I attended a presentation by Mariaelena DiBenigno and Khanh Vo – two Ph.D candidates at The College of William and Mary in Virginia – about what historians can learn from videogames.

Mariaelena and Khanh are both historians whose work focuses on how the public engages and interacts with history. For her dissertation, Mariaelena is researching how certain stories and interpretations become central to tours, exhibits, and online programs at historic sites and museums while Khanh is examining how toys and play inform identity and ideas of citizenship.

It is through the lens of these two projects that they began investigating how video games tell historical stories – including what makes good storytelling. In order to learn more I interviewed the two of them about this project, their favorite female characters, and, of course, Star Wars.

The two of you are working on a project that connects history to videogames. Can you tell me a little bit more about that project? How did this collaboration come about?

Mariaelena: [Last Spring] we started to talk about our respective interests in public history and how certain technologies – digital and otherwise – tell stories at sites near the College of William & Mary. Khanh told me a little about Assassin’s Creed III and I was totally intrigued by the ways it showed eighteenth-century history, from the really beautifully rendered costumes to the sound of horses on gravel. It really struck us as an example of not only public history but a different way to conceive of “living” history.

Khanh: When we talked about Colonial Williamsburg and Assassin’s Creed III as examples of different simulation of historical sites, I remembered seeing photographs of a man cosplaying as an assassin in Colonial Williamsburg. It kickstarted our conversation about the usefulness of gamification in public history.

What are you hoping to learn from this project?

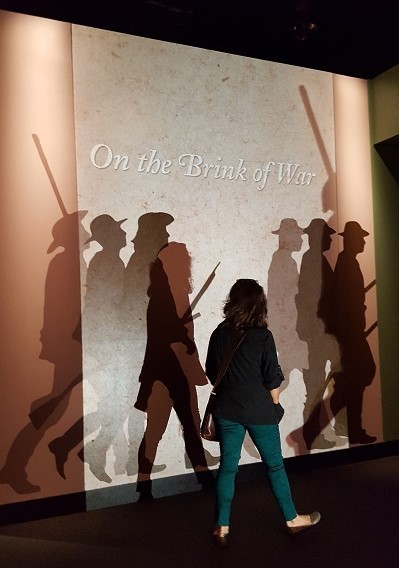

Mariaelena: It’s really helping me consider the different ways that history is public – whether historians and museum professionals like it or not, movies, novels, television shows and, yes, videogames are all public histories.

Khanh: As the digital humanities continue to grow as a field (and “digital humanities” have certainly become a buzzword in academia), I want to know what role technology plays in public history? How is technology being used? When is it un/necessary?

What drew you to gaming/videogames? What made you interested in gaming as a public history tool? What do you enjoy about videogames and gaming as part of your work/and for fun? What are some of the challenges of being a gamer?

Mariaelena: I’m a sucker for a good narrative hook, especially when that hook asks you to consider perspective or another’s point of view. I’ve been noticing an uptick in museum’s use of firsthand narratives, in order to draw visitors into the past and demonstrate necessary connections between now and then. The videogames that Khanh and I encountered also encouraged such connections, however awkwardly or problematically structured, while telling really interesting stories. And I’m always on the hunt for how popular culture influences and/or becomes public history – I see that happening with games like Assassin’s Creed.

Khanh: You cannot be bad at reading a book or listening to music, but you can be bad at playing a video game and the game will punish you for it. That’s what makes it fun. My first game was Super Mario Bros. on the Super Nintendo system. Everything you need to know about game design can be gauged from the first 30 seconds of the game. And game design has only gotten more and more sophisticated in its ability to render complex and intricate stories and characters. The affordances, the use of space, the level of built-in learning, and storytelling without relying on heavy blocks of text, these elements map perfectly onto the works of public historians and public sites.

For me, the biggest challenge of being a gamer is the labels because they come with certain restrictions and expectations. What does it mean to be a gamer vs. a female gamer, a serious gamer vs. a casual gamer, and so on? These labels are built on preconceptions that reinforce and perpetuate inequalities within the gaming industry. Gamergate certainly influenced my decision to disengage from the larger gaming community. More than the fear of harassment, it’s the need to have to defend myself when gender discrimination is indefensible and all I want to do is play a game.

As historians we often think about storytelling as we think about the past. In your opinion how important is storytelling to the presentation of history? How does your work with material culture and folklore connect with how we think about stories in pop culture?

Mariaelena: I love this question, as I am currently working through several popular novels that use historical moments to encourage questions not only about individual pasts but also how past events inform present conditions. In essence, I think that storytelling is integral not only to how humans connect with each other but also how to show, paradoxically, how far we’ve progressed and how much more we need to learn. Museums and historic sites always have a story to tell; often, it’s multiple, conflicting stories. Popular culture can allow for these multiple, conflicting stories because it is not beholden to accuracy and its often reflective of society at large – and pop culture inspires (often unwittingly) affective responses that can be lacking in museum scripts.

Khanh: As a student and a scholar there’s often a need to put our research within a theoretical framework. I’ve always been more interested in telling the story because the theory is in the story. Whatever the role of an historian should be, I agree with Mariaelena that storytelling is about connection, empathy, and learning from past experiences. Looking through archival materials and seeing the types of material objects people choose to attach to themselves, it tells us what they want us to remember about them. The preservation of such material objects indicate whose story is valued and worth preserving. More than objects stored in museums and archives, pop culture disseminates these stories on a far greater scale and it has so much influence on whose story gets told.

Do you have a favorite female character in literature?

Mariaelena: As a kid, I loved Anne Shirley – from Anne of Green Gables. She’s probably still a favorite, though I’m also fascinated by Shirley Jackson’s female characters, like Eleanor from The Haunting of Hill House – even though I don’t necessarily identify with them.

Khanh: Elinor Dashwood from Sense and Sensibility and Anne Elliot from Persuasion. I didn’t always like these characters, but I grew to appreciate them.

What makes their story resonate with you?

Mariaelena: Anne was never afraid to be smart, she was never afraid to challenge others. For all the saccharine elements that I recognize now, as an adult, I still appreciate Anne’s tenacity and courage. She refuses to be like everyone else, from her insistence on pursuing a career to her willingness to imagine out loud.

As for the Jackson protagonists, I just feel like they are a time capsule for female confinement. They’re terrifying character studies in what happens when we don’t encourage imagination or we limit it to the periphery of female experience.

Khanh: Elinor and Anne were written as sensible, demure women. I read them as very passive and it was quite frustrating because I wanted my heroines to be active. As I reread these book years later, I found a resilience and a quiet strength in their characters. They’re forgiving and patient even to characters who don’t deserve it. But then again, it’s not about deserving. It’s okay to be polite and sensible.

As fans of Star Wars, tell me about why the franchise resonates with you.

Mariaelena: I like seeing how it bridges generations, creates connections between parents and children. I’ve been able to share my Star Wars love with nieces, nephews, friends’ kids. It’s really cool to have a common pop culture language! Also: I love the new(er) female leads, in addition to Princess Leia, and I enjoyed the backstory provided in Rogue One – it gave narrative to a period of Star Wars “history” that I always wondered about!

Khanh: I was a six years-old immigrant who hardly spoke English and, yet, I was quoting Yoda before I knew what Star Wars was. “Do or do not, there is no try.” The ability of the franchise to transcend its origins and become a cultural touchstone is fascinating because it’s so much more than a retelling of the hero’s journey or a sci-fi adventure movie. Its characters and the universe have become so iconic that I can’t imagine what a world without Star Wars would look like.

Priya Chhaya is a historian who loves the written word. When she’s not reading anything she can get her hands on she is writing about the past and its intersection in our daily lives on her personal blog …this is what comes next.

- Imagining a New World at FUTURES - January 10, 2022

- Escape to WandaVision - February 24, 2021

- Regency Daze and the Magic of an RPG - January 5, 2020