Linda Interviews Alexander Freed

Alexander Freed is a writer’s writer.

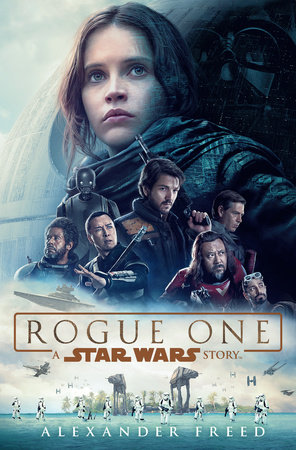

I don’t mean the stuffy type of writer who is hard to read and only high school English teachers like. To the contrary, Alexander Freed stories are great reads, whether he’s written storylines like the Imperial Agent or the Hutt Cartel for Star Wars: The Old Republic MMORPG, or comic books like The Old Republic: Lost Suns, or novels like Rogue One: A Star Wars Story. They are well paced, have engrossing characters, and a satisfying finish. Not stuffy, not boring. The reason I call him a writer’s writer is because he’s passionate about the craft of writing and he’s generous about what he has learned in his fifteen-year career. A perusal of his blog, AlexanderFreed.com, has good information for game writers in particular, but the tips are useful for all writers and an intriguing read for game players.

I sat down and chatted with Alex about a number of things and learned he prefers as few distractions as possible so doesn’t listen to music while writing; that he and Shelly Shapiro, the Del Rey editor who hired him to write Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, both lived in the same neighborhood of Philadelphia; and that Alex has a lot to say about the art of writing with lots of practical advice.

- It must be a challenge to go from a screenplay, which is telling a visual story, to novel, which is using prose to tell the same story. How did you approach that?

Going into the project, one of my goals was to ensure that the novel justified its own existence – to make sure that it wasn’t just a lesser, longer version of the film, but a distinct and worthwhile take on the same story. A book simply can’t capture the visual lushness and spectacle of a film; but a book can get inside characters’ heads in a way a film can’t. I tried to dig as deep as I could into the emotional state of the characters, into how their pasts inform their current choices, and so forth – I didn’t believe I could outdo or equal the “external” narrative of the film, but I could try to offer a compelling “internal” narrative to match.

Moving the story into prose was also the impetus behind the “Supplemental Data” entries in the book – excerpts from in-world documents, memoranda, and messages. Folks have talked about director Gareth Edwards’s almost documentary style of camerawork. I wanted to have an element of that documentary feel, but find an approach unique and appropriate to the medium.

Finally, a book also has room to meander a bit, to explore and take advantage of a more languid pace. I used that opportunity to flesh out some subplots that might have bogged down the film (particularly the material at the rebel base).

I really wanted the end result to feel less like an adaptation and more like a novel the film could have been adapted from – like a work that was already in its natural medium. Whether I succeeded is, of course, a judgment left to the reader.

- Did your background writing story lines for MMORPGs, like Star Wars: The Old Republic, where there are multiple moving parts to a project help you with writing Rogue One?

To be a great writer, you must be brilliant. To be a working writer, you must be able to juggle schedules and conflicting demands and revision requests with grace and professionalism; brilliance is nice but optional (and absent, I think, in my case!).

Lucasfilm and Del Rey did everything they could to make my life as easy as possible on this project – but a film like Rogue One is being tinkered with until the very last minute, and there are a hundred other tie-in projects that a novelization ought to enhance instead of trample on. If I hadn’t had experience working on large teams with tight deadlines, hadn’t known how to write material that (for lack of a better term) “plays well with others,” hadn’t known how to rigorously schedule myself, then I might have failed disastrously. I’ve learned a tremendous amount during my time in the video game world, and I remain grateful to everyone in that industry who taught me what I know now.

- Not having the benefit of seeing the movie, knowing how scenes were edited, what the score sounded like, how did you choose which viewpoints to tell the story from?

That was one of my first tasks when I sat down with the script: breaking the film down into chapters and scenes, and figuring out who would serve as the viewpoint character for each sequence.

When I’m writing original material, I typically build scenes around characters – there’s no question whose head I want the reader to be in. Here, I had to figure out not only which character had the most at stake in every scene, but also what unique perspective they might have to offer – and what I was okay leaving out (because not every character will notice everything going on in every scene – the audience may see something in the film that a viewpoint character in the book simply doesn’t care about).

(Some past Star Wars novelizations used an omniscient point of view, jumping between characters within a scene – that’s a style that easily fits a film, I think, but it loses some intimacy and it’s a technique I haven’t used enough to be fully comfortable with. That alone was enough reason not to go that route – this wasn’t the book for me to try stylistic experiments with!)

Some of my favorite moments in the book involve emphasizing the unique perspectives various characters have on one another. Just how differently do Jyn and Cassian interpret the situation they’re in at any given point? Does General Draven have any respect for Mon Mothma at all? K-2SO is funny to the audience, but is he funny if you’re standing right there? Viewpoint is key to that sort of stuff.

- After working on the novelization and imagining the movie as you wrote it, what was it like to experience the movie itself?

Surreal! For most of the running time, I was just looking for differences (and similarities) between the book and the film – surprising line readings by the actors, bits of background scenery, and so forth. Occasionally I’d lose track of the actual sequence of events because I was so focused on the tiny details. (“Oh, wait – we’re on Mustafar already? I was too busy looking at the costuming…”)

It was also great fun to observe the audience around me and watch the reactions. I wasn’t in any position to form an objective opinion of the movie, but the people around me were – so it was with great relief that I saw how much they seemed to enjoy themselves.

Oh, and I happened to see it in Sweden, so I tried to pick up a bit of Swedish from the subtitles. That was fun, too! (I did not, in fact, learn any Swedish.)

- You’ve written in almost every type of story telling genre for Star Wars—comics, novels, video games—do you find you work differently with different mediums? Do you have a favorite?

As we talked about in regards to the film to book process, every medium has its own strengths and weaknesses, and is best at telling a distinct kind of story. For me, that’s the joy of it – comics, for example, can emphasize visual spectacle the way no other medium can, because a comic book artist can draw a scene that would bedevil any set designer or 3D modeler. A game’s interactivity and visceral immersion is totally unlike anything else, and every game feels full of opportunities to pioneer new techniques. And of course, a book can get inside characters’ heads in an extraordinarily intimate way.

A lot of my pleasure in writing is constructing the best story I can using the tools at my disposal. My process, though, is very similar across the board. I’m a meticulous planner, so whether I’m writing a short story (where the only person affected is me) or a video game (where I need to coordinate with a massive team of designers and artists and programmers), I try to sketch out as much as I can as soon as possible. Comics are a bridge between the personal, one-man endeavors of novels and the hundred-person collaborative enterprises of video game development.

Working with collaborators can be intensely rewarding, and brings strengths I can’t possibly offer to a project. Prose gives me a level of personal control – every word is mine – that I can’t get anywhere else. I wouldn’t give any of them up if I had a choice. (I’m probably a better video game writer than I am a comic book or prose writer, but why should that stop me?)

- Who do you find more interesting: Jedi or Sith? Or having written a lot of non-Force users (the characters from Rogue One, Theron Shan in Lost Suns, the Imperial Agent story line for The Old Republic) – is it neither?

I really do enjoy writing “ordinary” characters in wild, fantastic worlds – whether it’s Imperial spies or rebel infantry grunts or what-have-you. That’s partly because I find their perspectives and conflicts interesting in their own right – How do you get by and strive toward what matters in a world where gods walk the earth? How do you deal with moral shades of gray in a galaxy where absolute good and evil exist? – but it’s also because there’s a lot of relatively fresh Star Wars territory to explore there.

That said, I do love the mystical side of Star Wars, on both the Jedi and the Sith sides of the coin. I feel like there’s a lot to be explored about how characters perceive the Force: how the Force’s existence affects one’s outlook on life, the rituals and philosophies developed around it, and so forth.

- Are there any upcoming projects you can share with us?

Lots of projects going on, very little I’m ready to share, alas. I spent much of 2016 working with video game studios – including a stint with my old colleagues at BioWare (where I did a tiny jot of work on the upcoming Mass Effect: Andromeda, and more substantial work on stuff I can’t discuss yet). More game announcements are forthcoming, along with a gorgeously illustrated comic project I’m hoping will finally see the light of day. Nothing I can say about books other than that I love working in prose and don’t intend to quit.

I encourage folks who want specifics to occasionally check my website, alexanderfreed.com, or to follow me on Twitter at @AlexanderMFreed. I try to mix my self-promotion in with useful advice on writing; it’s more tolerable for everyone that way.

- The (Re)Ascendancy of Thrawn - February 19, 2022

- Get your Chiss On: A Review of Thrawn Ascendancy Chaos Rising - September 17, 2020

- Review: Shadow Fall (a Star Wars Alphabet Squadron Book) - June 26, 2020