New Insights on the Flawed Finale: The Rise of Skywalker Revisited

Nearly nine months have passed since the theatrical premiere of The Rise of Skywalker, and in that time Lucasfilm has released a number of nonfiction and fiction sources that provide additional insight into the flaws in the finale film of the Sequel Trilogy. The Art of The Rise of Skywalker by Phil Szostak and The Skywalker Legacy documentary help to show how the flaws came about during the creative process. The first of two posts on The Rise of Skywalker Revisited examined how those sources, and others, reveal the story process origins of the dissonant redemption of Kylo Ren in the last hour of the film. This second post considers what those sources reveal about other key characters in the Sequel Trilogy.

Equally interesting are the insights derived from the subsequent fiction directly connected to The Rise of Skywalker which has been published in the months following the film: Rae Carson’s novelization, Michael Kogge’s junior novelization, and The Rise of Kylo Ren comic mini-series by Charles Soule and Will Sliney. (As of this writing, the comic adaptation of the movie by Jody Houser and Will Sliney is the only previously announced Star Wars title that has not been restored to Marvel’s slate of upcoming issues following the several months of company-wide pandemic-related hiatus earlier in the year.) Soon after the movie’s theatrical release, FANgirl Blog published a six-part series of posts analyzing its many storytelling and characterization failures. Would the subsequent fiction double down on these failures, simply try to ignore them, or make attempts to mitigate the harm? Some of those flaws, like the insignificant characterization for Leia due to relying exclusively on Carrie Fisher’s prior footage and dialogue or the abrupt and poorly explained introduction of the Force dyad between Rey and Kylo Ren, potentially could be ameliorated or improved with further elaboration through omniscient narration, character point-of-view, or newly created conversations. Other flaws, such as Finn’s shortchanged character arc, are so deeply ingrained in the structure of the film itself that additional storytelling would functionally have to rewrite the story to make a meaningful improvement.

Unsurprisingly, the subsequent fiction followed the expected path: adding some clarity or perspective on the margins, but shying away from any substantive reimagining of the movie version of The Rise of Skywalker. But perhaps there was little that could be done. On page 110 of Kogge’s novel, Finn reacts to Hux’s revelation that the general is the mole within the First Order in a telling bit of internal monologue: “This all seemed too wacky.” In the end, maybe this simple expression encapsulates as accurately as anything the irreparable nature of the flaws and failures of The Rise of Skywalker.

Leia

Unlike the film, the novelizations of The Rise of Skywalker were not constrained to the limitations of the previously filmed footage and dialogue of Carrie Fisher. Both Carson and Kogge took advantage of this opportunity to expand Leia’s role in the story and give more insight into her motivations. For the Leia scenes taken directly from the movie, the ability to include internal monologue in particular offers much more heft to her appearances than the film provided.

Both novels include a version of a scene between Leia and Maz at the Resistance base on Ajan Kloss involving Maz handing Luke’s lightsaber to Leia. Interestingly, each author portrays this scene with extensive internal monologue from Maz and only the same two words of dialogue from Leia (“True path…”), which strongly suggests that this was a scene from the movie’s script based on unused footage from The Force Awakens (in fact, the saber handoff appears in the first Episode VII teaser trailer) and may have been a relatively late excision during the movie’s editing. Both novels also explicitly incorporate the idea that Leia has never fully recovered physically from her ejection into space during the destruction of the Raddus’ bridge, so that her remaining time with the younger heroes and the Resistance is limited (though the specific timing of her death comes as a shock to Poe and a regret to Lando, neither of whom was able to say goodbye before her passing). Carson’s novel twice takes a moment to address The Last Jedi in another way, as well, by clarifying that the First Order had interfered with Leia’s distress call from the Crait base, so that her allies had failed to respond not because of a lack of hope, but because they had never received the message in the first place.

In addition, each novel contains a number of new scenes to elaborate Leia’s story. Carson’s novel, for example, opens with an extended sequence of Leia’s tutelage of Rey. These pages not only give more time and depth to the movie’s flashback sequence of Leia training with Luke, but also more fully ground Leia’s role and values as a Jedi teacher than the movie was able to portray. Carson also weaves in a running thread of Leia exchanging dialogue with the spectral voice of Luke, with her brother gently advising her that her time to pass into the Force has come and Leia rejecting the guidance in her inimitable way because she has one thing left she must do in this life when the moment is right. Kogge’s portrayal of Leia’s point of view in the moment of her death finds her finally making peace with her father Anakin as she prepares to try to reach the light left within her son. Ultimately, though, while these passages and scenes bolster Leia’s portrayal on the margins, they cannot remove her from the very limited role the screenplay of The Rise of Skywalker gave her.

That conclusion only emphasizes how much was lost for Leia, and for the Star Wars franchise, when the decision was made to sharply limit her role in The Rise of Skywalker to Carrie Fisher’s previous footage. It seems that is also the origin of the story decision to write Leia’s death as a moment of fridging her iconic character in service of creating an emotional trauma significant enough to change the soul of her son. In The Skywalker Legacy documentary, Chris Terrio explains: “Leia’s Jedi trial happens in Episode IX. The end of her path as a Jedi is fulfilled when her son turns back to the light.”

Yet the information revealed after The Rise of Skywalker makes clear that the problems in Leia’s storyline in the Sequel Trilogy have their roots far earlier than the third film. The Art of The Rise of Skywalker quotes excerpts from the transcript of the May 2014 Intellectual Property Development Group meeting at which an even more ambitious idea was discussed, in the form of Dave Filoni’s suggestion that (p.35): “We should shift it so Leia is the Obi-Wan of this entire trilogy. I don’t even think it hurts that she’s not primarily that mentor figure in VII because, like John [Knoll] has been saying, the audience expectation is so on Luke. And when that proves not to be true, it’s way more powerful.” But that ambitious notion never took hold. The Skywalker Legacy reiterates the longstanding Lucasfilm talking point about the original intention for Episode IX to feature Leia as its principal legacy character, following Han in VII and Luke in VIII – likely grounded in the fact that Rian Johnson’s story for The Last Jedi had rejected the Jedi mentor role for Leia before The Force Awakens everreleased in theaters. Leaning fully into Luke as the Jedi mentor for Rey in the second film limited Leia’s Jedi Master role in the third film into serving as a substitute rather than the primary guiding influence.

Ultimately, the fundamental flaw can be seen in a quote from production designer Rick Carter in The Art of The Rise of Skywalker when he says (p.34): “The full heroine’s journey is Leia’s. If you look at the big steps from infancy to mortality, she’s the one who’s been through everything.” In a superficial sense it is true that we see Leia’s birth in the Prequel Trilogy, her youthful leadership of the Rebellion in the Original Trilogy, and the culmination of her military, political, and Jedi paths before her death in the Sequel Trilogy. But it is not accurate to call her story in these films a journey – at least not in the mythic storytelling sense that applies to Star Wars characters like Luke, Anakin, Kylo Ren, Finn, and Rey. Her role in the story may advance along with the in-universe chronology, but Leia’s character development and growth is mostly inferred or occurring off-screen, rather than centered as the principal events within the films. And she had that fate in Star Wars long before Episode IX.

Finn

Stormtrooper deserter turned Resistance general Finn is the other character most significantly short-changed by The Rise of Skywalker compared to the previous films in the Sequel Trilogy. After a Hero’s Journey parallel to Rey’s in The Force Awakens and a second heroic cycle in The Last Jedi, Finn’s character is static in The Rise of Skywalker’s conclusion to the trilogy. He doesn’t even finally get a surname, as Rey does. And there is not much Carson and Kogge could have done to increase his role in the story without writing an entirely new subplot for him.

One of the most disappointing aspects of Finn’s story in The Rise of Skywalker is the way in which the film hints at a revelation that Finn is Force-sensitive and part of the same awakening as Rey, yet ultimately fails to make the reveal or deliver on the promise of that potential. The novels seemingly were limited in a similar way. Kogge keeps the pertinent scenes virtually the same as the film, without elaboration. Carson includes a small amount of material more explicitly referencing the Force from Finn’s point of view, and the joyful reunion embrace among Finn, Rey, and Poe at Ajan Kloss includes an implicit acknowledgement from his friends (Rey saying, “I know,” followed by Poe adding, “We all know.”). But Finn’s connection to the Force is kept oblique with instincts and feelings, without an overt display of his power or a promise that he holds a future as a Jedi. As with Leia, the novels could seek to add a bit on the margins, but only within the parameters of Finn’s underlying story in the film.

Since December 2019, John Boyega has repeatedly expressed his disappointment with his character’s story in the third film, including the movie’s unwillingness to make Finn’s Force-sensitivity explicit. In an interview published by British GQ on September 2, 2020, Boyega shared broader criticisms about his participation in Star Wars, as well, including the bait-and-switch marketing of Finn with a lightsaber for The Force Awakens and his character arc in The Last Jedi.

Moreover, The Skywalker Legacy shows that his hopes for Finn were not simply the desires of an actor for his character, but rather part of his understanding of the character’s importance to the story throughout the production of the Sequel Trilogy. In a clip alongside Naomi Ackie during filming for the attack on the Star Destroyer at Exegol, Boyega says “This is a passionate moment for us, seeing a Black man and a Black woman lead a cavalry of heroes. I’m proud.” But that sentiment is preceded by Boyega’s explanation that: “I always wanted this to happen. I always wanted there to be some form of a stormtrooper rebellion, which was something I was quite interested in since VII. And it felt like J.J. was going towards that anyway.” It is easy to understand why a Black actor would find personal and cultural resonance – and contemporary timeliness – in the thematically powerful story arc of a formerly brainwashed child soldier becoming a leader who instigates and inspires others like him to rise up against their oppressors and free themselves from mental and political tyranny, as well. In The Rise of Skywalker, however, that idea is reduced to Finn fighting alongside fellow former stormtroopers while blasting away at the Final Order’s own conscripts. Though Boyega in the British GQ interview seems to personally lay the blame on studio executives rather than Abrams, his disappointment in how his character’s story ended is justified regardless.

Rey

In contrast to Leia and Finn, Rey does not have her central prominence in the overall plot of The Rise of Skywalker diminished compared to The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi. Nevertheless, her portrayal in the film suffers from a number of significant problems, particularly with the inconsistencies between the third film and its predecessors in her motivations and characterization. Notably, the Carson and Kogge novelizations can do little to repair these flaws because they are intrinsic to choices made in crafting the story of the film.

Both novels, for example, confirm that during her weeks of training on Ajan Kloss, Rey is having troubling visions in the Force but is not telling Leia about them. One of Rey’s fundamental lessons in The Last Jedi, however,was that her keeping secrets from Luke had resulted in the downward spiral of circumstances on the Supremacy and at Crait – yet neither the movie nor the novels are able to provide a characterization reason why Rey would ignore this lesson and keep more secrets from her next teacher, Leia. Similarly, both novels incorporate the notion that Rey is afraid of darkness inside herself, or a dark future for herself, even before she learns she is related to Palpatine – yet this has very little grounding in the first two films, and it is hard to see why even a disturbing Force vision would so thoroughly rattle Rey’s self-confidence given what we have seen from her previously. Likewise, both novels attribute Rey’s growth as a Jedi to her training with Luke and Leia, paying off in her connection with the Jedi spirits at Exegol – but when it comes to taking the name Rey Skywalker in the final scene, Carson simply repeats the scene from the film while Kogge adds only a brief amount of point-of-view narration to explain Rey’s surname decision. The film itself is the constraining factor in Rey’s portrayal, and there is no rewriting around that.

Ironically, despite years of often condescending opining by some fans and commentators toward the years of speculation regarding whether Rey was or was not a blood relative of the Skywalker family – with such scorn typically grounded in self-confident assertions of the speculation’s supposed pointlessness or its purported textual misunderstanding of the films – the recently revealed information confirms that the narrative tension from which that speculation arose has in fact been part of the story process itself all along. The Art of The Rise of Skywalker includes two telling quotes from the May 2014 IPDG meeting. Pablo Hidalgo says (p.37): “I like the idea that she’s going to be our Skywalker, but she’s not a Skywalker. Then, for our purposes, ‘the Skywalker’ is really a metaphor. It doesn’t have to be something that’s directly connected to blood.” Similarly, Kiri Hart explains (p.36): “It is cool to think about how then that character is pulled in and sort of adopted by the Skywalkers. But she doesn’t have to be a Skywalker. People can have resonance and a role to play no matter where they start out.” (It is also worth noting that these quotes, reinforcing content included in all three Art of the Sequel Trilogy tomes, fully debunk the fanon notion that Ben Solo, rather than Rey, was ever intended or understood to be the true heroic protagonist of the Sequel Trilogy by the individuals involved in creating and making the films.) In the December 2016 draft of Colin Trevorrow’s Episode IX, Duel of the Fates, Rey is not related to the Skywalkers or to Palpatine; her surname is revealed to be Solana, and she keeps it when she returns to her friends and takes up the mantle as the new leader of the Jedi. That script also gives this theme emotional resonance when Kylo Ren, doubling down on his cruelty in The Last Jedi, declares “You are nothing! You are no one!” and Rey’s rejoinder is the powerful assertion that “No one is no one.”

While it is easy to see how this idea plays out over the three films ultimately made, it is also easy to see how it generated so much fan speculation. Fans of the previous six-movie Skywalker Saga would have no reason to expect the third trilogy’s protagonist to be (or become) a family member only metaphorically. And however much Lucasfilm might have hoped an online press release could shuttle best-selling novels aside into Star Wars Legends, an expectation of familial connection in the next-generation characters of the Skywalker saga would come naturally to anyone with even a passing knowledge about the flagship storylines unfurled across three decades of officially licensed Star Wars paratext in the Expanded Universe.

Even more, The Skywalker Legacy reveals that none other than J.J. Abrams was among those holding such a contrary view. Discussing Rey’s destiny he says: “The balance of the Force is never a permanent, enduring thing. The idea that this is the story of a character who needs to step up and bring balance in her own way. If you had asked me in the middle of doing VII, where would we go with Rey, the headlines would be exactly the same.” And at another point in the documentary he admits: “The idea that she’s so crazy powerful with the Force, so quickly – for us, we always felt that there was a connection between her and something that would help explain some of these things.” Although the specific decision to implement this idea by juxtaposing the grandson of Vader against the granddaughter of the Emperor seems to have been reached during the development of Episode IX, it only reinforces that interpreting Episode VII as not foreclosing the possibility of Rey having a kinship relation to the Skywalkers (or some other established character) in fact aligns with the perspective held by the co-writer and director of The Force Awakens.

On September 8, 2020, Daisy Ridley appeared on ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel Live for an interview with guest host Josh Gad. Her erstwhile Murder on the Orient Express co-star previously had shared on social media several videos in which he fruitlessly (and hilariously) sought to obtain Sequel Trilogy spoilers from her. Accordingly, it was no surprise that Gad asked Ridley about the family lineage reveal in The Rise of Skywalker. Describing the evolution of the trilogy’s story over time, Ridley answered:

“At the beginning there was toying with an Obi-Wan connection. There were different versions. Then it really went to that she was no one. It came to Episode IX and JJ pitched me the film: it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, Palpatine’s your granddaddy!’ and I was like, ‘Awesome.’ – and then two weeks later he was like, ‘Oh, we’re not sure…’ So it kept changing. Even as we were filming I wasn’t sure what the answer was going to be.”

Of course, as FANgirl Blog has elaborated previously, the fact that the creators of the Sequel Trilogy did not have a consensus on the identity of their central heroic protagonist resulted in numerous other problems for Rey’s story across the three films – but it does demonstrate that fans were not wrong to see ambiguity within films that never had a definitive answer behind the scenes to begin with.

Kylo Ren

The previous post in the Rise of Skywalker Revisited series thoroughly assesses the story process origins, from the early conceptions of the Sequel Trilogy to the final film, of Kylo Ren’s dissonant and unearned redemption that occurs abruptly at Kef Bir before Ben Solo’s final sacrifice at Exegol. Nonetheless, it is worth briefly discussing here how the stories released subsequent to the movie shed further light on Lucasfilm’s approach to the character.

As with Rey, there is no rewriting around the fundamental character arc portrayed onscreen in the film. Both Carson and Kogge maintain Kylo Ren’s characterization as a confident and unhesitating dark side menace – including an intention to kill Palpatine to seize total power for himself, as well as to kill Rey if she will not turn to the dark side – until his mother reaches out to him moments before he will strike Rey down. Both retain the conversation with his memories of his father, rather than adding to the telepathic connection from his mother. Carson’s version of the scene provides some additional point of view as Kylo Ren decides to become Ben Solo once more, but this only reinforces that the abrupt change of heart is not founded upon characterization groundwork built across the three films, instead simply counting on the parallel to his grandfather to try to make the moment work.

On the other hand, it is notable how the subsequent fiction reconceives Kylo Ren’s backstory, seemingly in an attempt to increase the sense of tragedy in his fall to the dark side so that his return to the light is more credible. Much is made of Palpatine’s line of dialogue from the film (and trailer): “I have been every voice you have ever heard inside your head.” Carson, Kogge, and Soule all implement this remark literally, as an indication of long-term telepathic manipulation, rather than as a metaphorical reference equivalent to the Devil on the shoulder within the young man’s own moral descent. More than Carson, Kogge places significant emphasis on the idea that the voices in his head played a substantial role in creating the mistrust and resentment that led Ben Solo to break with his family. The second issue of The Rise of Kylo Ren even includes a telepathic conversation between Ben and Snoke while the teenager is seated in the same starship cockpit as Luke Skywalker and Lor San Tekka.

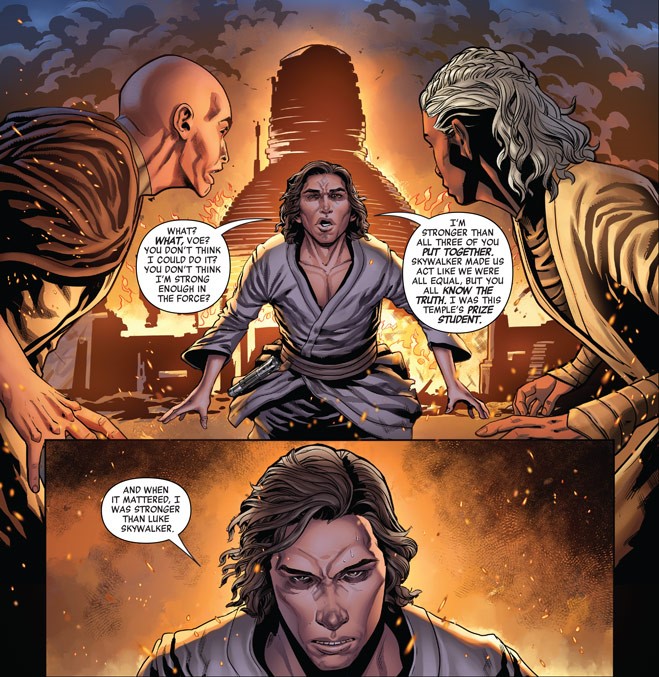

Other aspects of The Rise of Kylo Ren, however, reinforce that Ben Solo bears full personal responsibility for his decision to choose the dark side. The comic portrays Luke as a kind and wise mentor who takes note of Ben’s emotions and personal interests. Fellow Jedi students, especially Tai, consider Ben a colleague and friend (if perhaps also somewhat arrogant) and care about his well-being. But Ben resents the burden of his family legacy and the expectations placed upon him, and feels it gives him no choice in deciding his own destiny. He also resents being named after a great Jedi Master because it implies he must live up to Kenobi’s example, and derides as a lie that his surname is not even his father’s real family name. (Ben references other unspecified lies by his family, as well, without mentioning directly his parents and uncle having concealed the truth about the identity of his grandfather prior to the public revelation of his family heritage in Claudia Gray’s novel Bloodline.) On the fateful night at the Jedi temple, The Rise of Kylo Ren subverts the expectation created by The Last Jedi by showing the fire at the Jedi temple, and the dead students on its grounds, as resulting from a massive explosion rather than the direct actions of Ben Solo personally. As he leaves the place, Ben hesitates at killing three young Jedi who return to the grim scene and briefly considers going to his mother for help. Instead, he seeks out Snoke and then the Knights of Ren – and by the end of the four issues Hennix and Tai are dead, Ben has personally killed the gang’s leader and his fellow pupil Voe, and he has reforged his lightsaber into the red blade of Kylo Ren.

Taken together, these aspects of the subsequent fiction fit the pattern discussed in the previous post: an unwillingness to commit to a different character arc for Kylo Ren, and instead hewing his fate to a copy-paste of his grandfather’s. Rather than a timely villain driven to the dark side by the worst impulses of his own ego and selfishness, Ben Solo is a replay of Anakin Skywalker, manipulated for years by Palpatine to mistrust the Jedi and seek more power. And just as Anakin did not intend that his decision to betray Mace Windu and spare Sidious would lead to the full horror of Order 66, so too Ben did not intend that his clash of lightsabers with Luke Skywalker would lead to the destruction and massacre of the training temple.

But what is missing from Ben Solo’s reconceived backstory is a reason – within the story – why he would have kept secret from his family the voices in his head and the disturbing accusations and temptations they shared with him. With Anakin in the Prequel Trilogy, the sources of his mistrust are clear: he misses his mother; the Jedi teach him only to repress emotions; his Master is holding him back, unwilling to let him reach his full potential; he must conceal the secret marriage to Padmé that would get him expelled from the Order; Yoda shows no compassion for his fear of losing someone he loves; and, ultimately, he knows the Jedi will not be willing to help him save Padmé from dying. Nothing comparable is established in the story for Ben Solo. If dark voices are whispering terrible things in his mind from a young age, why does he not tell anyone? He has no secret marriage to conceal, no repercussions of theological orthodoxy to expect if he tells his parents or his uncle the truth. As with his abrupt redemption, the story simply relies upon the parallels to his grandfather to impute characterization into the stages of Ben’s fall to the dark side. Rather than a rhyme, similar but not identical, his story is merely a reprise.

The Dyad in the Force

Like the antagonist’s backstory, The Rise of Skywalker also reconceived the story dynamic between Rey and Kylo Ren. After the film’s release, fans and movie critics alike expressed confusion about what the “dyad” is, when and how it had come into existence between the two, and how much narrative weight it was meant to carry in the story. The extrinsic sources indicate that this confusion is understandable – because the storytellers themselves did not hold a clear sense of its meaning.

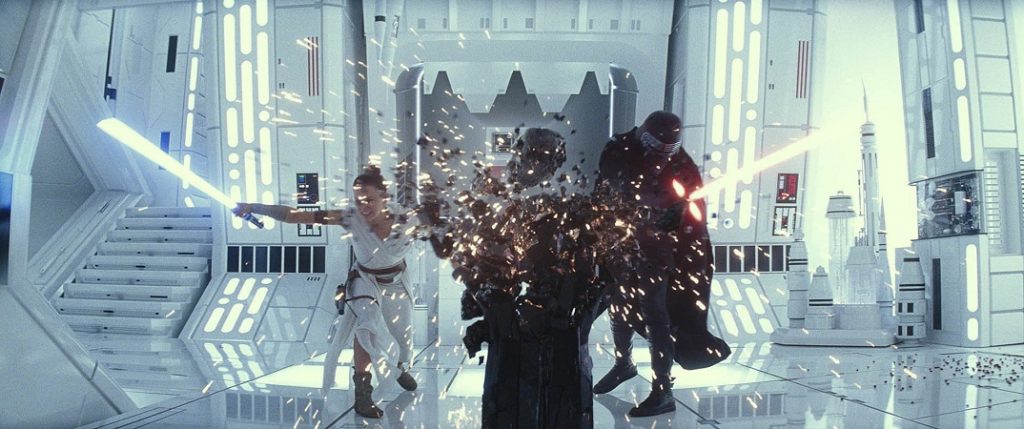

The subsequent fiction provides little clarity. Kogge’s novel is the most overt, describing Rey and Kylo Ren as “twins of the Force” juxtaposed to the Skywalker twins Leia and Luke and carrying a similar mythical (and non-romantic) significance. Carson’s novel takes no overt position on the meaning of the dyad, leaving its meaning for the reader to discern (and certain passages could be read to connote a soulmate interpretation, were the reader so inclined). Both novels portray the brief kiss at Exegol from Ben Solo’s point of view, declining to provide direct insight into Rey’s mindset in that moment (and thereby eliding, as the film does, why Rey would wish to kiss the man who had been her nemesis and tormenter for the previous two and a half movies). The Rise of Kylo Ren takes place long before the events of the third film, though one small panel does include Rey: a scene of the girl with Unkar Plutt, speaking aloud a sensation of cold at the moment Ben Solo kills Ren, the leader of the eponymous Knights, with the intention to take his place. The same two-page spread also shows Leia feeling her son’s dark deed through Force, as well as reactions from Snoke and ghoulish Exegol Palpatine. Perhaps the dyad as such already exists, or perhaps Rey experiences a portent of her future; this brief moment in the comic also is left open to interpretation.

The nonfiction materials reveal a similar variation in understanding. In The Art of The Rise of Skywalker, Rick Carter describes (p.34) Leia’s final act as “the catalyst for the two primary antagonists—the male and the female, being bonded in a life force,” but this idea of attributing the dyad to Leia apparently dropped away as the story process unfolded. In an interview shortly after the movie’s release, Chris Terrio remarked that the dyad was deliberately left open to interpretation, including “whether that was a mistake that Palpatine made by bridging them and therefore creating this thing.” The Rise of Skywalker Visual Dictionary by Pablo Hidalgo appends the adjective “prophesied dyad” to the connection, though the final film (and the novelizations) do not rely on prophesy so much as rarity to make the dyad sound special. The Visual Dictionary also retcons previous understandings so that the two already were mystically linked when Kylo’s interrogation of Rey in The Force Awakens first bridged their minds, and so that Snoke was aware of their status as a dyad during the events in the throne room in The Last Jedi.

In The Art of The Rise of Skywalker (p.62), Chris Terrio discusses the dyad in terms similar to Kogge’s novel: “The two of them are this dyad in the Force. They are twins of fate, twins of destiny.” In The Skywalker Legacy documentary, Terrio elaborates on this idea: “What if your sort of soul mate in the Force was your enemy? Circumstance pits them against each other, but the Force bonds them together. They understand each other almost from a point of view of fate, and yet fate has made them enemies.” Driver gives a similar assessment from the perspective of his character: “He learns over the course of the movie that they’re two halves of the same thing. I think it just, if anything, reaffirms what he knows intuitively and has known for a while but hasn’t been able to articulate, until he can.”

Later in the documentary, Terrio further explains the function of the dyad in the story. “We began talking about them as a mythic concept, which is in Joseph Campbell, which is the mythic dyad. That they’re two parts of the same whole. And then finally we began talking about how if the dyad ever came together, its power would be immeasurable.” But that power is not what it seems. “The hope at the beginning of the film that Sidious articulates is that the dyad will come together on the dark side. But the reversal is that the dyad does come together, and it is as powerful as we expected, but they come together on the side of the light.” The dyad is not the power to conquer and rule the galaxy, but the power of life: Ben achieves the power his grandfather never did, saving Rey from dying by selflessly giving his own living Force to her. Given the preexisting themes of Star Wars, however, it is unclear why the creators of The Rise of Skywalker believed a new concept like the dyad was necessary to justify that story moment. In the end, the nature of the dyad is just as confused behind the scenes as it is within the story.

The End of the Skywalker Saga

The flaws and failure of The Rise of Skywalker on its own terms are challenging enough for the Star Wars franchise, but they become all the more compounded because Episode IX was meant to serve as the epic ending of the nine-movie Skywalker Saga. Yet the tone envisioned by its creators leaves much to be desired.

The Art of The Rise of Skywalker includes an extended quote from Rick Carter (p.133): “Star Wars is a tragedy with a happy ending. How do you earn that? Star Wars is really just Apocalypse Now with a happier ending. Essentially, you go to a temple and you encounter darkness. And you have to determine whether you’re going to become the darkness or not. … Coppola could leave that movie when Willard walks out of the temple. But Star Wars has to go another step, go that far and then redeem it.” Similarly, in The Skywalker Legacy he clarifies: “At the heart of this movie is a darkness. It’s part of Rey’s journey to confront this darkness that’s been there from the very beginning of The Force Awakens.” This is followed immediately by Terrio explaining: “We knew from the beginning that there would be a Heart of Darkness-y structure to this movie, and that this would be about Rey’s journey to the darkest place, both in the galaxy and for her. But we had to work a lot to figure out exactly what that was.” Of course, Joseph Conrad’s novella was an inspiration for Apocalypse Now itself – and also is the subject of sharp criticism in the field of postcolonial studies, from the perspective that Conrad’s critique of European colonialism nevertheless perpetuates racist tropes in doing so. If Lucasfilm had been genuinely interested in delivering a conclusion to the Sequel Trilogy which was thematically timely in the manner of George Lucas’ Original Trilogy and Prequel Trilogy, then taking different and more contemporary source material as inspiration would have been advisable.

And besides, why would it make sense to think that the proper inspiration for the epic finale of the Skywalker Saga should be tragedy? The Last Jedi already had given Luke the same tragic arc as his father: a terrible mistake of judgment followed by years of isolation and a self-sacrificial death. Yet The Rise of Skywalker shapes Leia’s arc in her father’s image, as well: fear of a Force vision coming true ultimately causes that tragic event to occur anyway. In Revenge of the Sith, clearly a Shakespearean tragedy by any measure, Padmé dies as Vader is reborn in the dark side; in The Rise of Skywalker, Leia dies as Kylo Ren is reborn in the light side. And Ben Solo himself has the same tragic tale as his grandfather Anakin, from Jedi youth to selfish fall to the dark side to years of dark deeds to a final fatal self-sacrificial redemptive action. Rey Skywalker’s last scene in the movie includes a new lightsaber, a new name, and a sunrise – but the story of the rest of the family has concluded in tragedy. It is difficult to understand why Lucasfilm believed this was the right thematic tone on which the Skywalker Saga should end.

.

Related Links:

- Rey Deserved Better: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 1 (Jan. 2020)

- Fridging Leia Organa: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 2 (Jan. 2020)

- The Fates of Kylo Ren and Ben Solo: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 3 (Jan. 2020)

- Finn’s Unfulfilled Potential: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 4 (Jan. 2020)

- The End of the Skywalker Saga: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 5 (Jan. 2020)

- The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 6 (Jan. 2020)

- The Story Process Origins of a Dissonant Redemption: The Rise of Skywalker Revisited (Sep. 2020)