Star Wars’ Mother Problem

Solo is a film full of the familiar. From its beginning to its end, it chronicles the adventures of characters long established in the Galaxy Far, Far Away, but it also introduces something rare in the cinematic offerings of the Star Wars universe: a mother who raised her child and, presumably, did not meet some horrible end. The mother in question is one of the unnamed parents of Lando Calrissian, whom Donald Glover references with overflowing adoration and love in a passing moment. It was both a pleasant surprise and an indictment and symptom of the franchise’s dominance by male creators. Under their guidance, mothers in Star Wars mainly exist to suffer and die for the benefit of other characters’ stories.

It began in A New Hope with Beru Lars being reduced to smoking skeletal remains. At the same time, unsaid in the movie, is the murder of Princess Leia’s mother, Breha, with the destruction of Alderaan by the Empire’s super weapon. While the two fathers also bite the dust, specifically for the purpose of the story Luke’s adoptive mother Beru exists entirely to die and provide young Skywalker with the freedom to respond to the call to adventure offered by Obi-Wan Kenobi and Leia’s recorded plea for help. Alone, by itself, it is not entirely problematic and leans into archetypical constructs in storytelling to push the hero along his journey. After all, one only needs to watch about 90% of the Disney animated film collection to note the death of a mother figure (or both parents) for the film’s hero.

It began in A New Hope with Beru Lars being reduced to smoking skeletal remains. At the same time, unsaid in the movie, is the murder of Princess Leia’s mother, Breha, with the destruction of Alderaan by the Empire’s super weapon. While the two fathers also bite the dust, specifically for the purpose of the story Luke’s adoptive mother Beru exists entirely to die and provide young Skywalker with the freedom to respond to the call to adventure offered by Obi-Wan Kenobi and Leia’s recorded plea for help. Alone, by itself, it is not entirely problematic and leans into archetypical constructs in storytelling to push the hero along his journey. After all, one only needs to watch about 90% of the Disney animated film collection to note the death of a mother figure (or both parents) for the film’s hero.

In Return of the Jedi, after the siblinghood between Leia and Luke is revealed, we learn that their non-adoptive mother likewise had died, off-screen. The manner in which the fate of the woman we now know as Padmé Amidala was referenced in the original trilogy had damning reverberations in the next trilogy. To put it frankly, the prequel trilogy is terrible for mothers.

Shmi Skywalker is introduced as the GFFA’s Mary, as in Mary mother of Jesus, and exists as the vehicle of the Force’s immaculate conception of Anakin Skywalker. While Pernilla August is stupendous in the role, her character’s purpose in The Phantom Menace is relegated to being the bearer of the news of his birth and the connection he must break to join the Jedi. Shmi’s character’s reappearance in Attack of the Clones is even more egregious: Anakin’s mother dies purely to advance the downward trajectory of his character arc toward becoming Darth Vader. Incredibly, the exact same thing happens with Padmé Amidala’s character in the next installment, Revenge of the Sith.

Shmi Skywalker is introduced as the GFFA’s Mary, as in Mary mother of Jesus, and exists as the vehicle of the Force’s immaculate conception of Anakin Skywalker. While Pernilla August is stupendous in the role, her character’s purpose in The Phantom Menace is relegated to being the bearer of the news of his birth and the connection he must break to join the Jedi. Shmi’s character’s reappearance in Attack of the Clones is even more egregious: Anakin’s mother dies purely to advance the downward trajectory of his character arc toward becoming Darth Vader. Incredibly, the exact same thing happens with Padmé Amidala’s character in the next installment, Revenge of the Sith.

Amidala appears in all three films of the prequel trilogy and in the first two had purpose, first it in the role of Queen of Naboo protecting her people from invasion and then as a member of the Galactic Senate. She’s dynamic in both films and avoids being a passive character drifting along the plot to serve other characters. However, by the end of the first act of the final prequel film, we learn that she has become an expectant mother to her and Anakin’s children. This announcement signals the end of Amidala being anything but a device to see Skywalker become the villain of the original trilogy. While Shmi Skywalker’s death pushed Anakin further down the path of the Dark Side, Padmé’s death completes it, and that is the extent of her presence in Revenge of the Sith. Motherhood, at least in the cinematic Star Wars universe, stripped one of its best female characters of her agency at the service of the male protagonist.

Despite the passage of time and acquisition of Lucasfilm by Disney, the trend of reducing mothers to plot devices and their absence as character attributes continued into the sequel trilogy era. While Rey waits on Jakku for her family to return, it’s her mother whom we presumably see the young Rey crying out to in her Force vision in The Force Awakens. In the same film, the absence of parents is a key feature to Finn’s character as a child reared in the ways of the First Order. Likewise, the Tico sisters in The Last Jedi are orphans.

Despite the passage of time and acquisition of Lucasfilm by Disney, the trend of reducing mothers to plot devices and their absence as character attributes continued into the sequel trilogy era. While Rey waits on Jakku for her family to return, it’s her mother whom we presumably see the young Rey crying out to in her Force vision in The Force Awakens. In the same film, the absence of parents is a key feature to Finn’s character as a child reared in the ways of the First Order. Likewise, the Tico sisters in The Last Jedi are orphans.

The early death of a mother even became a striking part of Poe Dameron’s biography when it was completely unnecessary to do so. Poe’s parents are not referenced The Force Awakens, but were introduced in a comic miniseries produced by Marvel in the lead up to the film. Shara Bey, a rebel pilot at the Battle of Endor, who enlists as a companion in secret missions by Luke and Leia, was a fantastic addition to the canon. The series concludes with Bey and her husband, Kes Dameron, retiring to Yavin IV to raise young Poe. Then, in a book released in the same time frame, Before the Awakening, one sentence off-handedly noted that Bey died a few years later from disease. The only reason to kill Shara off in such a manner was because someone determined Poe Dameron’s background necessitated the loss of his mother at an early age.

The standalone films have their own problems. Rogue One was not immune to the same dysfunction of reducing mothers to biographical necessities to determine the nature of our protagonists. Lyra Erso, scientist and mother to Jyn Erso, does not even make it through the first five minutes of the film – killed dramatically when Orson Krennic arrives to take her and her family into custody to force Galen Erso to rejoin the Death Star project. Whereas there was no canonical reason why Lyra’s character could not have been swapped with Galen, the decision was made that it should be the mother who dies to further the protagonist’s character. While Lando compliments his mother, two of the other featured characters in Solo are orphaned.

The standalone films have their own problems. Rogue One was not immune to the same dysfunction of reducing mothers to biographical necessities to determine the nature of our protagonists. Lyra Erso, scientist and mother to Jyn Erso, does not even make it through the first five minutes of the film – killed dramatically when Orson Krennic arrives to take her and her family into custody to force Galen Erso to rejoin the Death Star project. Whereas there was no canonical reason why Lyra’s character could not have been swapped with Galen, the decision was made that it should be the mother who dies to further the protagonist’s character. While Lando compliments his mother, two of the other featured characters in Solo are orphaned.

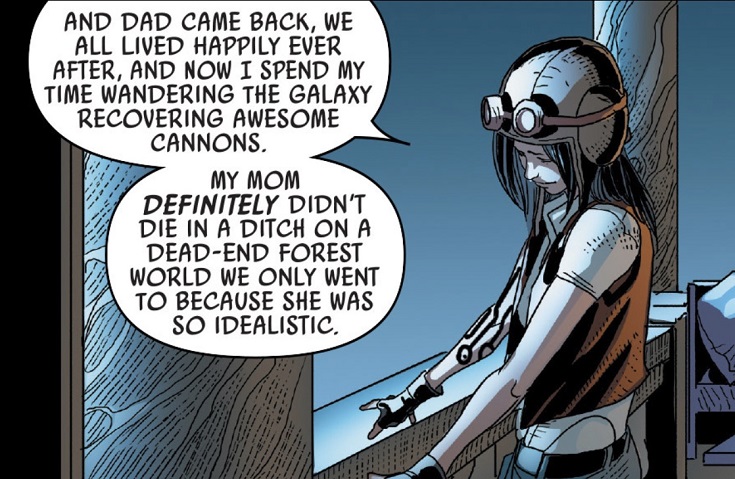

The absence or death of mothers carries along elsewhere in the franchise. One of the best new characters added to Star Wars, Dr. Chelli Aphra, was introduced in Marvel’s Darth Vader series. Immediately Aphra was recognized as a unique and wonderful character, and by the conclusion of the Darth Vader series run was granted her own titular series that remains ongoing at this time. Aphra, at least initially, was a supporter of the Galactic Empire’s goal of instituting order out of the chaos of the Clone Wars. While on a mission for Darth Vader to discover whether Anakin Skywalker and Padmé Amidala had children, Aphra relates a story from her youth to explain why order is preferable over the alternative. It’s the story of her mother’s death. Aphra’s father, meanwhile, is allowed to feature as a major character in a story arc later.

On the television screen, another standout female character, Hera Syndulla of Star Wars Rebels, suffers as well from a deceased mother in the character biography syndrome. Sabine Wren’s mother, Ursa Wren, is notable as one of the rare mothers who survives.

On the television screen, another standout female character, Hera Syndulla of Star Wars Rebels, suffers as well from a deceased mother in the character biography syndrome. Sabine Wren’s mother, Ursa Wren, is notable as one of the rare mothers who survives.

In the novels, one woman stands out as the exception, too. Chuck Wendig’s Norra Wexley is a mother who not only survives, but thrives in the Aftermath Trilogy. Like Shara Bey, Wexley is another rebel pilot and veteran of the Battle of Endor, but so far, she has not been written into a death to benefit her son, Temmin “Snap” Wexley, a character who still exists in the sequel trilogy.

For the most part, however, Wexley and Wren are the exceptions that drive home the ongoing problem within the Star Wars franchise: mothers generally exist to drive the stories of their children with little to no regard for their own characterization.

For the most part, however, Wexley and Wren are the exceptions that drive home the ongoing problem within the Star Wars franchise: mothers generally exist to drive the stories of their children with little to no regard for their own characterization.

There could be several reasons for why this problem plagues the franchise. As mentioned before, the absence of mothers and their deaths have long been a part of the Western story telling tradition. (It’s a reason why stepmothers also tend to be the villain a lot.) Beyond this, however, is the uniformity of the storytellers – mostly men who bring their own preconceptions and biases to the characters they create and write. It’s entirely possible that one reason mothers are absent or killed off because those writing the story simply do not think or realize that they can fill the same character role the fathers fill – think of Lyra Erso and Galen Erso, for example, or even more recently, the characters Val and Beckett in Solo. It’s why representation matters on all levels of the creative process. Until this changes, mothers will continue to suffer as plot devices that exist to serve other characters, and more often than not, their sons.

- Star Wars The Mandalorian – The Reckoning and Redemption Review - January 15, 2020

- Star Wars: The Mandalorian –The Prisoner Review - January 11, 2020

- Star Wars Resistance – Station to Station Review - January 7, 2020