Wonder Woman Unshackled

There is a moment of epiphany in a book when all the singular elements of the plot come together. It is as if a veil has lifted and all the puzzle pieces finally snap into place. This is a familiar feeling for historians. At times we are equal parts Leslie Knope, analytical and methodical, or Nancy Drew hunting for evidence in the historical record. It is in that hunt that we realize we are working on a completely different puzzle than the one we originally started on.

Such is the case with Jill Lepore’s The Secret History of Wonder Woman. Lepore, a Harvard historian and contributor to the New Yorker, was researching two completely different articles on Planned Parenthood and the lie detector when she stepped back and realized both had a common denominator: the creator of Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston.

Using a trove of never-before-seen documents from archives and the Marston family, The Secret History digs deep into the evolution of Wonder Woman — not just from the moment of her debut in 1942 after Marston was hired by DC Comics as a psychologist, but starting over forty years earlier with the beginning of Marston’s life. But it’s not just Marston’s story that we inhabit – rather Lepore reveals how Wonder Woman was born not just from his experience, but also from the experiences of his wife Elizabeth Holloway Marston, his mistress Olive Byrne, Olive’s aunt Margaret Sanger, and Olive’s mother Ethel amongst others.

The lives of Marston, Elizabeth, and Olive were anything but normal. All three lived under one roof with their respective children: Marston fathered two with both women. The arrangement was a closely guarded secret – to the point where Marston’s children with Olive didn’t know he was their father until adulthood. As we learn about the Marston family Lepore highlights how this non-traditional household reflected some of the tensions for women’s rights in the early 20th century.

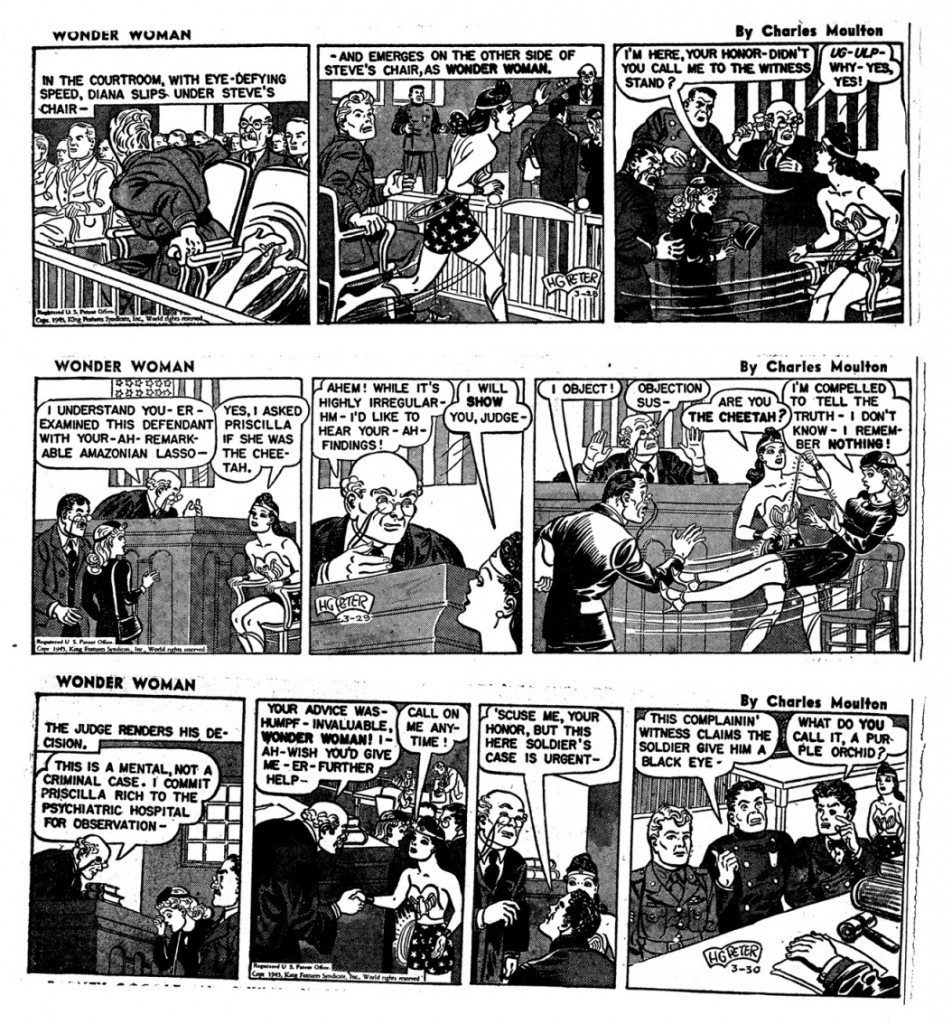

The relationship between Wonder Woman’s character and Marston’s life are undeniable, from Holloway making a conscious (following an ultimatum from Marston) decision to allow Byrne to live with her so she could continue to work, or Marston engaging with research on emotion and psychology via his development of the lie detector. Lepore meticulously links panels from the Wonder Woman comics with narratives from the Marston household. For example, in 1928 Olive Byrne, to maintain secrecy and hide her children’s parentage, changed her name to Olive Richard after “marrying” a man named William K. Richard who later passed away. Richard was a fabrication, but after this event images show her wearing two thick bracelets, one on each hand. While she stayed at home with the kids Richard also wrote for the Family Circle. In the August 14, 1942 issue, Olive writes how she went to find out more about this new comic book character Wonder Woman—as merely a reporter without any intimate connection to Marston. From The Secret History:

“The Doctor hadn’t changed a bit,” she reports. “He was reading a comics magazine, which sport he relinquished with a chuckle and rose gallantly to his feet, a maneuver of major magnitude for this psychologic Nero Wolfe.”

“Hello, hello, my Wonder Woman!” he calls out to her.

“What’s the idea for calling me Wonder Woman?” she wants to know. (It gave them a great deal of pleasure, their game of hide-and-seek.)

He explains to her that her bracelets were the inspiration for Wonder Woman’s bracelets. He hands her a copy of Wonder Woman. She is dazzled.

“I opened the book to read, ‘This amazing girl, stronger than Hercules, more beautiful than Aphrodite,’ and so on, and I remembered that my sons had argued as to whether she could lick the whole Japanese army all at once or whether she’d have to take them a few thousand at a time. The Doctor beamed when I told him this and said, ‘That’s right, the kids love her’” (Lepore, 231-232).

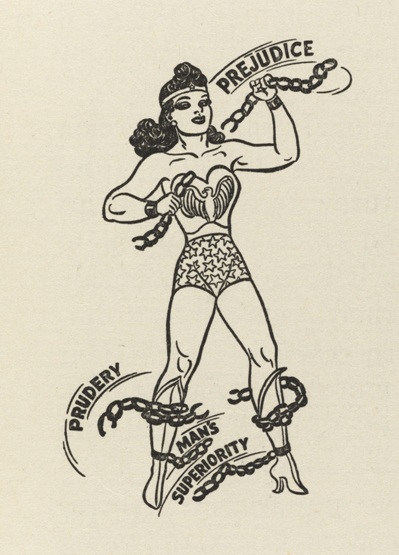

Marston saw women as being constantly shackled by society debuted Wonder Women with the words “The only hope for civilization is the greater freedom, development and equality of women in all fields of human activity” (Lepore, 219).

The strength of The Secret History of Wonder Woman is that Wonder Woman is embedded in a broader historical context—not just in terms of feminism and equal rights, but also the history of sexuality, psychology, police work, and comic book history–providing readers with a history that is layered and complex. Lepore doesn’t just stop with Marston’s death in 1947, instead tracing the evolution of Wonder Woman and her alter ego Diana Prince into the ‘60s and ‘70s. In doing so she emphasizes how as views of feminism changed Wonder Woman’s story lines became less about breaking free, and more about conformity. Perhaps the most telling example is how the inserts in the comics, which in Marston’s time were called Wonder Women in History and included stories about individuals such as Susan B. Anthony, shifted to inserts about weddings called Marriage a la Mode (Lepore 272). All this being said, the icing on the cake for The Secret History of Wonder Woman are the sketches of the costume in development. Panels from various issues illustrating Wonder Woman’s evolution all add to this engaging and thoughtful book.

One final note on cultural history, The Secret History of Wonder Woman emphasizes the importance of looking at characters in time as well as space. Each of our beloved characters, whether they be male or female, are to some extent a product of their time – either as a reflection of society’s expectations or a glimpse into what could be and where we could be. As we look to the future of female characters we should look for one’s that are more than just what we expect but also what we want and need.

In an interview Jill Lepore states that Wonder Woman is an amalgamation of the different ideals of Margaret Sanger, Olive Byrne, Elizabeth Holloway and William Moulton Marston.

“Wonder Woman isn’t only an Amazonian princess with badass boots. She’s the missing link in a chain of events that begins with the woman suffrage campaigns of the 1910s and ends with the troubled place of feminism fully a century later. Feminism made Wonder Woman. And then Wonder Woman remade feminism, which hasn’t been altogether good for feminism. Superheroes, who are supposed to be better than everyone else, are excellent at clobbering people; but at fighting for equality they’re hobbled by the fact that they’re supposed to be better than everyone else, and equality isn’t about being better than everyone else. Most people still carry around the idea that feminism has come in waves, the first wave ending in 1920, with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, and the second wave starting in the 1960’s with the Feminine Mystique. But restoring the Wonder Woman of the 1940s to the history of that struggle makes clear that feminism hasn’t come in waves; it’s been a river, wending.” (From Knopf Q&A)

You can read a portion of Lepore’s research in this New Yorker article or in this Smithsonian magazine article.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a copy of this book.

Priya Chhaya is a historian who loves the written word. When she’s not reading anything she can get her hands on she is writing about the past and its intersection in our daily lives on her personal blog …this is what comes next.

- Hyperspace Theories: Lucasfilm’s New Era Officially Begins - January 31, 2026

- Hyperspace Theories: Two 2025 Superhero Movies Show Star Wars’ Missed Path - January 19, 2026

- Hyperspace Theories: WICKED FOR GOOD Changes for the Better - November 28, 2025

Pingback:2015. Another Year. Another Resolution. | ...this is what comes next