The Book, the Movie, and the Story of The Hunger Games

When a story told in a favorite book is retold as a movie, many fans tend to view the book as the perfect version of the tale and the movie as an inherently imperfect – if not inferior – alteration of the original. This is an understandable perspective. For one thing, first impressions matter a great deal in all aspects of life, so reading the book first unconsciously sets the parameters against which later iterations of the story are judged.  For another, reading a book is an extended and deeply immersive experience; extended because it takes hours if not days to read a novel, and deeply immersive because reading requires a constant exercise of the imagination to envision what is described in mere words on the page. When watching the movie version of the story later, it is only natural that the relative brevity and passivity of that experience pales in comparison to what we saw and felt in our personal mind’s eye.

For another, reading a book is an extended and deeply immersive experience; extended because it takes hours if not days to read a novel, and deeply immersive because reading requires a constant exercise of the imagination to envision what is described in mere words on the page. When watching the movie version of the story later, it is only natural that the relative brevity and passivity of that experience pales in comparison to what we saw and felt in our personal mind’s eye.

But movies also can entertain in certain ways that are superior to books. By combining visuals, sound effects, and music, a movie can interact with multiple parts of our brains simultaneously, triggering emotional or physical reactions that prose never could. How many times, for example, have you seen someone leap out of their chair from fright reading a book, compared to flinching or gasping or shrieking at a scary moment in a movie theater? Similarly, action sequences or fight scenes that look great on film might be difficult, if not impossible, to write in prose with anywhere near the same level of speed, intensity, and pulse-pounding thrill.

Ultimately, books and movies are two very different mediums for telling stories, and there will always be ways in which each one could never match the other. For that reason, asking how the movie version of a story compares to the book version of a story really is, as the old cliché goes, like comparing apples to oranges. Instead, at the core of both the book and the movie is the story being told, whether that story is Harry Potter or Twilight or The Hunger Games. The author can make the book version as good a book as it can be, and the director can make the movie version as good a movie as it can be – turning the story into the best possible apple and the best possible orange – but each version will still have its own inherent strengths and weakness as a medium for telling the underlying story they share. By reference to that underlying story they have in common they are both adaptations, and neither one will be perfect.

Last weekend’s release of The Hunger Games movie has generated a lot of fan discussion about the differences between the book and the film. Some fans have expressed disappointment, even outrage, at various aspects of the book that were “left out” or “changed” in the movie. Other fans have praised the new material in the movie for expanding the story or increasing its impact compared to the book. And some, like a parent with two children, love them both just as much, but in different ways.

For that reason, The Hunger Games is a great illustration of how the book version and the movie version can exploit the advantages and downplay the disadvantages of the respective mediums to tell the same underlying story to great effect, but differently. Of course, some fans inevitably will prefer one version to the other – but neither version can succeed without a captivating story to tell in the first place.

Katniss Everdeen is the heroine of The Hunger Games, far and away its central and most important character in both the book and the movie. Yet because the two versions tell her story in different mediums, a series of other differences in the storytelling cascade from there. In the book, the story unfolds exclusively from Katniss’ first-person narrative point of view. In some ways, this draws the reader deeply into caring about Katniss and her fate; in other ways, it limits the amount of information the reader can learn about Panem, its politics, and the Games because we only see and know what Katniss sees and knows.  The movie mirrors this close focus on Katniss, keeping Jennifer Lawrence onscreen nearly the entire film. But the ability to cut away from her limited perspective – to the Gamemakers and the control room, to President Snow and Seneca Crane, and to the television coverage – actually increases the dramatic tension for the movie audience compared to the book, because the additional information shows us that Katniss is in far greater danger than she realizes.

The movie mirrors this close focus on Katniss, keeping Jennifer Lawrence onscreen nearly the entire film. But the ability to cut away from her limited perspective – to the Gamemakers and the control room, to President Snow and Seneca Crane, and to the television coverage – actually increases the dramatic tension for the movie audience compared to the book, because the additional information shows us that Katniss is in far greater danger than she realizes.

While much of the book takes place within Katniss’ internal monologue, the movie forgoes the technique of voiceover narration, and these storytelling choices work well for their respective mediums. By drawing in the reader to use his or her own imagination, the book emphasizes Katniss’ intensely personal experience of living the events; by showing the events unfold before our eyes, the movie emphasizes the story’s political allegory about the toxic possibility of reality television as a tool for tyrannical oppression. Exposition about the purpose and operation of the Games that comes in Katniss’ internal monologue in the book is conveyed through external sources in the movie – the Capitol’s propaganda film before the Reaping, Haymitch’s dialogue with his mentees, or the cutaways to Flickerman and Templesmith reminding their viewers about the trackerjackers – that are equally effective, and sometimes even more chillingly disturbing. Similarly, in the book Katniss deduces the clues Haymitch is sending her indirectly with the parachutes, and this works for the reader because we can follow her thought process as she figures it out. But without her narrative in the movie, the story works better by cutting to the quick with Haymitch’s pointed note: “You call that a kiss?”

This shift in storytelling perspective even has implications for the portrayal of Katniss’ motivations and the scope of the ending, without changing the core story. In the book, Katniss’ internal monologue is focused on her primary goal of getting back home because she needs to be there for her mother and Prim; her goal of winning the Games is secondary, because that is the only way to make her main goal possible. Consequently, after Katniss does win the Games the reader needs the catharsis of the full aftermath of the Games, seeing the benefits and dangers from her victory and her realization that her defiance of the Capitol has actually threatened her ability to achieve the goal of keeping her loved ones safe after all. On the other hand, when Katniss’ objective is set out in the movie’s dialogue, her goal becomes to win – as she promises Prim and Gale, tells Caesar in her interview, and discusses with Peeta and Haymitch. It’s not that Katniss doesn’t want to get home to those she loves, but rather that for the movie audience her primary objective is winning the Games.  Accordingly, the film is able to significantly trim down the number of post-Games scenes to just the key points that are needed to bring catharsis to the movie audience. The core story in the two version is ultimately the same, but the book plays up Katniss’ internal motivations while the movie focuses on her words and deeds.

Accordingly, the film is able to significantly trim down the number of post-Games scenes to just the key points that are needed to bring catharsis to the movie audience. The core story in the two version is ultimately the same, but the book plays up Katniss’ internal motivations while the movie focuses on her words and deeds.

The portrayals of other characters also gain the benefit of different viewpoints for the audience in the movie. Over the course of the story, Haymitch transforms from fatalistic drunkard to cautiously interested mentor to deeply invested champion pulling out all the stops to save the lives of his charges. In the book, Katniss is constantly doubting how much she can count on Haymitch to help her, wondering when his next drunken binge will sabotage her chances of survival. During the Games, she even fears she has been abandoned until the parachutes begin to arrive. In the movie, on the other hand, the audience gains the benefit of information Katniss herself lacks – we can see that his pride in her apple shot and his dismissiveness toward Effie are genuine, and we know from the start that he is paying close attention to the Games and working the sponsors to get what he needs for his tributes. In that way, his character arc is actually clearer and more resonant for the movie audience, because we can see it for ourselves instead of hearing it filtered through Katniss’ anxiety and mistrustfulness.

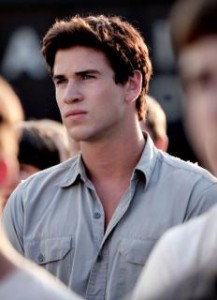

Similarly, the Reaping occurs very early on in both the book and the movie, and Gale remains behind in District 12. Yet he is an important character in Katniss’ life and the trilogy’s story, so it is important to keep him present throughout. In the book, past-tense flashbacks during the Games revisit Katniss’ memories of moments with Gale, establishing his character and his actions toward her. The internal monologue also gives insight into how Katniss misjudged some of Gale’s actions and feelings in the past, just as she also misreads Peeta in the present. In the movie, though, flashbacks likely would be distracting and confusing, but the visuals provide other ways to establish the same elements. For example, the opening interaction between the characters shows their comfortable familiarity in the woods, and Gale’s protectiveness when he keeps an arm around her as the hovercraft flies over them; later, he doesn’t hesitate to scoop up Prim when Katniss volunteers, and he somehow finds a way to be the only other person than her mother and sister to get to say goodbye.  During the Games, real-time cutaways back to District 12 show that Gale initially doesn’t watch it on television like he suggested in the meadow, but then he needs to watch to his best friend’s fight to win. Yet the movie does not reveal everything: are his scowls from disgust at what the Capitol expects Katniss to do to win, or from concern that she might genuinely be developing feelings for Peeta? At the end, though, Gale stands proudly cheering for the victors, Prim atop his shoulders, and a brief exchanged glance speaks volumes about the bond he and Katniss still share.

During the Games, real-time cutaways back to District 12 show that Gale initially doesn’t watch it on television like he suggested in the meadow, but then he needs to watch to his best friend’s fight to win. Yet the movie does not reveal everything: are his scowls from disgust at what the Capitol expects Katniss to do to win, or from concern that she might genuinely be developing feelings for Peeta? At the end, though, Gale stands proudly cheering for the victors, Prim atop his shoulders, and a brief exchanged glance speaks volumes about the bond he and Katniss still share.

The movie version of The Hunger Games also takes advantage of the strengths of the cinematic medium to bolster some of the thematic elements of the story. Katniss herself is unaware of the political impact of her actions until Haymitch explains them to her after the Games are over – but from the movie’s cutaways the audience knows all along how high the stakes have risen, including in the scenes with Snow and Seneca, the riot in District 11, and Haymitch himself suggesting the star-crossed lovers ratings bonanza to Seneca as a ploy to spare Katniss’ life after her defiant memorial for Rue. This foreshadows the rebellion in Catching Fire and Mockingjay much more overtly than the book’s limited narrative perspective. Similarly, in the book, Katniss simply experiences the Games occurring around her; in the movie, the cutaways make clear that Seneca and the Gamemakers are deliberately manufacturing events in the Games solely for the entertainment of the viewing audience in the Capitol, reinforced by the commentary of Caesar and Claudius. This make the reality television allegory far more powerful. So does the manner in which the movie deliberately avoids any voyeuristic appeal to gratuitous violence, the very thing The Hunger Games is allegorically condemning. In the book, for example, Thresh bashes in Clove’s head with a rock, a frighteningly quick death that is easy to envision from a prose description. To avoid the gore of such a killing onscreen, the movie deftly uses the strengths of the medium to portray an equally frightening and vicious death: a loud, sickening thump against the metal Cornucopia and a lifeless but bloodless corpse flopping to the ground.

Even though a movie is often necessarily much smaller in breadth and duration compared to a book, the core nature of the underlying story can be maintained even in the pared down version. For example, The Hunger Games movie reduces the number of parachutes that Katniss receives from her sponsors.  One of the eliminated parachutes is the sleep drug. In the book, Katniss sneaks it into Peeta’s food to ensure he will be unconscious when she breaks her word to him and heads to the “feast” at the Cornucopia to retrieve the medicine needed to save his life. In the movie without that parachute, Katniss never drugs Peeta – but she still breaks her word to him all the same, simply counting on his infection-induced feverish stupor to keep him incapacitated while she is away. Perhaps not affirmatively drugging him makes Katniss seem a little bit less ruthless, but her core breaking of her word to Peeta remains, and that is the fundamental characterization element of her decision in that scene. Similarly, as the Games are winding to a close Cato is trapped amid the fury of the muttations. In the book, from Katniss’ perspective it seems to take hours of waiting for him to die before she realizes the Gamemakers are forcing her to untie the tourniquet from Peeta’s leg to use her arrow to finish off Cato. In the movie, with the need to avoid voyeuristic graphic violence thematically more prominent, Peeta does not suffer a second gruesome leg injury – and Katniss draws an arrow and puts Cato out of his misery almost immediately. Perhaps this makes Katniss seems a little bit more compassionate, but it certainly works better in advancing the movie’s plot swiftly forward to the imminent catharsis of their victory in the Games.

One of the eliminated parachutes is the sleep drug. In the book, Katniss sneaks it into Peeta’s food to ensure he will be unconscious when she breaks her word to him and heads to the “feast” at the Cornucopia to retrieve the medicine needed to save his life. In the movie without that parachute, Katniss never drugs Peeta – but she still breaks her word to him all the same, simply counting on his infection-induced feverish stupor to keep him incapacitated while she is away. Perhaps not affirmatively drugging him makes Katniss seem a little bit less ruthless, but her core breaking of her word to Peeta remains, and that is the fundamental characterization element of her decision in that scene. Similarly, as the Games are winding to a close Cato is trapped amid the fury of the muttations. In the book, from Katniss’ perspective it seems to take hours of waiting for him to die before she realizes the Gamemakers are forcing her to untie the tourniquet from Peeta’s leg to use her arrow to finish off Cato. In the movie, with the need to avoid voyeuristic graphic violence thematically more prominent, Peeta does not suffer a second gruesome leg injury – and Katniss draws an arrow and puts Cato out of his misery almost immediately. Perhaps this makes Katniss seems a little bit more compassionate, but it certainly works better in advancing the movie’s plot swiftly forward to the imminent catharsis of their victory in the Games.

The Hunger Games is one of the rare stories that achieves success in captivating and emotional portrayals in two different mediums, in this case Suzanne Collins’ book and Gary Ross’ movie. Perhaps no movie version could ever have matched the intensely personal connection provided by the novel’s first-person narrative, but for the same reasons the book lacks much of the allegorical power from the movie’s visual impact. In the end, there’s no need to choose whether one version or the other is “better” – because fans of The Hunger Games are incredibly lucky to have two highly effective versions of the story to enjoy.

B.J. Priester is editor of FANgirl Blog and contributes reviews and posts on a range of topics. A longtime Star Wars fandom collaborator with Tricia, he is also editing her upcoming novel Wynde. He is a law professor in Florida and a proud geek dad.

I was really disappointed in the film. I thought that it had not of the resonance of the book. The violence was so sanitized that it left no impact on the horrific things happening to children. Also the editing of the film was so chaotic I was not able to focus long enough on a scene and this really hurt the death scenes in the arena. Lastly, everything happens so quickly there is not character development so I don’t really care about the death of anyone. The development that I have i had to bring in from the book and that just does not make this movie work.

In response to Mr. Rushing:

With respect, I don’t share your perspective on the movie’s “sanitized violence.” It seemed apparent that the filmmakers were sensitive to the fact that The Hunger Games’ broad audience base is, at its low end, quite young. It is unfortunately true that young teens, and even pre-teens, are now accustomed to seeing graphic violence in many forms of media but I do not believe that early initiation into open brutality is necessary. I appreciated the way that Director Gary Ross pulled back from explicit images of the horror in killing children, not for myself but for those kids sitting with their parents two rows in front of me. The movie made it clear that children died – and died horribly – plus I found that the auditory cue of the cannons, the visual round-up of death photos every evening, and the ways in which the living kept track of the dead had enough psychological impact to make the loss of lives extremely real. Not to mention, of course, that the fight-to-the-death nature of the Games was spelled out in a number of different ways. This was not just another TV episode of “Survivor.”

I have watched many graphically violent movies. Occasionally, I felt that the gore had its place within the context of those storytelling experiences. However, in The Hunger Games it seemed to me that there was plenty of emotional resonance in the characters, the situations, the cold political maneuvering. Rue’s death is the perfect example: a two-second view of a child pulling a weapon from her abdomen with blood spreading into the fabric of her shirt told the story. Beyond that, the shifting of her facial expressions, the movement of a hand-held camera showing the forest canopy from her point of view put me in Rue’s place, and her conversation with Katniss was evocative and poignant. Even the cut-away shots to her dead assassin spoke unequivocally of Katniss’ remorse over killing him, despite the fact that she did so defending herself and Rue.

The argument to show more violence for the sake of “impact” speaks precisely to society’s taste for voyeurism that is one of the problematic themes The Hunger Games wants us to question. As acknowledged cautionary tales, both the movie and the book beg us to rethink issues like showing children graphic violence, especially against characters who would be their peers. Why do we need to see the tearing of flesh, spurting of blood, or agony of twelve-year-olds? Have we so lost touch with our emotions that we cannot feel these things – cannot believe these things – unless bodies sprawl on the ground before our eyes? If that is true, then humanity has already set a few toes onto the dirt road toward a barbarous future that The Hunger Games plainly hopes we can avoid.

I admit that I have a bias on this subject. As a career Emergency Room nurse, I have seen graphic violence – with real blood and death – up close, too many times to count. To anyone who has only experienced gore on movie screens: consider yourself fortunate. Reality is not so beautifully choreographed.

For these and other reasons, I believe that the sanitized Hunger Games movie you saw is a kindness to young people in theater audiences around the world. Children are extremely perceptive. You may have wanted to see the violence; they didn’t need to watch it. They got the point.

As far as the “chaotic” editing (and perhaps the hand-held camera work) is concerned, I felt these movie-making choices caused the film to be more like the book, not vice versa. How else could Ross have so vividly portrayed Katniss’ point of view? Not everyone’s thought processes are orderly, precise, and logical. Katniss is an impoverished teen, forced into adult responsibilities and illegal activities simply to stay alive, when her life is made a living hell at the Reaping. Her thoughts – the story’s narrative – are necessarily chaotic.

Mr. Rushing, you also point out that you didn’t “care about the death of anyone” due to lack of the movie’s character development compared to the book. I would argue that the major deaths in the film – as in the book – are those of the Tributes from Districts 1 through 11. Aside from Rue, and perhaps on a lesser scale, Cato, are those characters really developed more in the book? They are perhaps described a little more fully, but I did not see much difference between written and visual character development for Foxface, Thresh, or Glimmer, unless you are making comparisons from the book, “The Hunger Games Tribute Guide”, which is a movie tie-in and therefore unrelated to Suzanne Collins’ original work.

In response to Lex and this blog:

So many people struggle with the translation of books to movies when they are completely different methods of conveying a story. You make excellent points for readers to consider when their expectations for seeing a favorite book appear unchanged on-screen. The two are different entities. If The Hunger Games was filmed verbatim, the movie would be four or five hours long!

Books have the luxury of pages filled with rich description and detail. Readers can pour over their words time and again, catching new details with every read.

On film, the audience needs to pay attention. Subtle looks, brief exchanges, even set pieces have larger meanings. Who caught the exact moment when Haymitch changed from reluctant member of the District 12 team to true mentor for Katniss? It was there. And what else was locked in that room with Seneca Crane and the bowl of berries? Something was, and it was meaningful.

I agree that books and movies have their own merits. It’s obvious to me now that the first time I watched the movie I was hoping to “see” the book. That is why I returned to the theater a week later for a second viewing, and in doing so, gained an entirely different perspective – and tremendous appreciation – for this entertaining and valuable film.

I understand what you are saying about the violence and I am not clambering for more gore for the sake of gore. What I am saying is what Collins said about why she wrote the book. She says in her interview with Scholastic that she got the idea from flipping channels and seeing youth compete for something on some show. “Then there’s the voyeuristic thrill—watching people being humiliated, or brought to tears, or suffering physically—which I find very disturbing. There’s also the potential for desensitizing the audience, so that when they see real tragedy playing out on, say, the news, it doesn’t have the impact it should.” So the desensitizing and sanitized violence of the movie I think actually worked against this film and the message that she was trying to achieve in the book (I personally always want the violence in a film to serve the story and not just be gore for the sake of blood; that holds little interest for me). The book is about the horrors of war, written to teens, so coming out of the movie (as I did reading the book) I should feel something. We should come out disturbed about what we have seen and be left with the question of whether we are anywhere close to this kind of behavior? And the sad part is we do children and teens are killed everyday for war and so much more.

What I was also disturbed at lack of development for the men in Katniss’ life, especially Peeta. The poor guy has nothing to do and because we don’t have her internal thoughts we don’t even get to speculate well as to what they could be. He is one of the most important characters in the story and we get nothing for him to do but try and look good and get hurt. In the book he is one of the most upstanding and righteous characters; we see him risking it all to give away bread to Katniss and his famous speech to her about wanting to stay true to himself still gives me chills. Now these are in the movie, but understated too much; I also think he is just miscast. Being the strong and silent type, you have to have onscreen presence and it just was not there for me.

On the other side, Jennifer nails Katniss and that is what leaves me hopeful for the next two movies. Perfect casting and acting in this film on her part!

Pingback:The Hunger Games: Catching Fire – Storytelling as Adaptation and Sequel « fangirlblog.com