From its inception in 2010, FANgirl Blog has analyzed and critiqued storytelling decisions in Star Wars and other major franchises, as well as reviewing and discussing books, comics, and other tales without such wide visibility. Global pop culture stories are particularly important, however, because they serve as our modern myths: they provide entertainment that not only reflects society by portraying values and moral dilemmas, but that also can shape how individuals and society understand themselves in the real world. Whether intentional or subconscious, the mythic Hero’s Journey remains a common storytelling pattern in many prominent stories released today. That is also why, from the beginning, FANgirl Blog has advocated for considering how, why, and to what extent a Heroine’s Journey would be different.

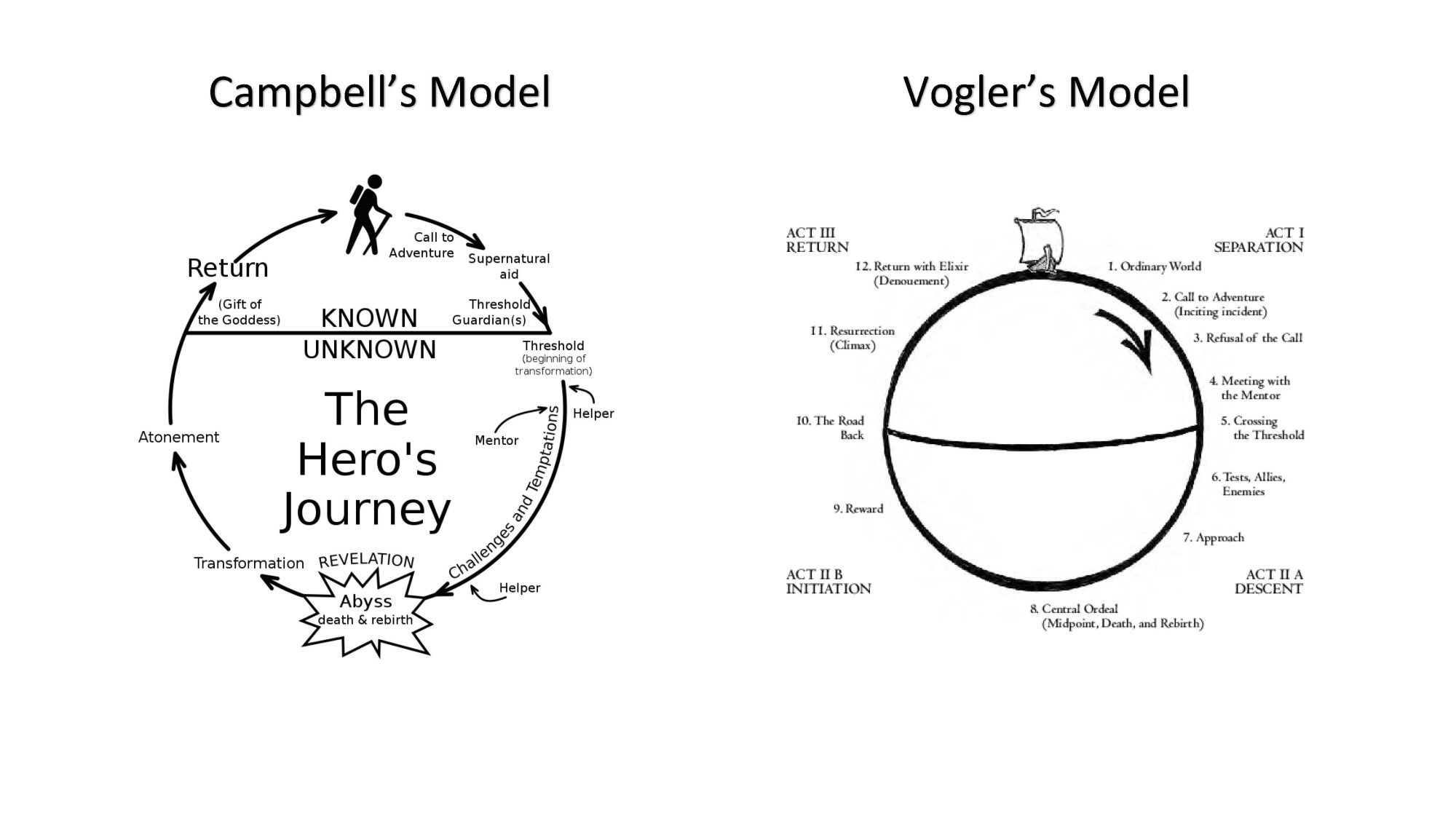

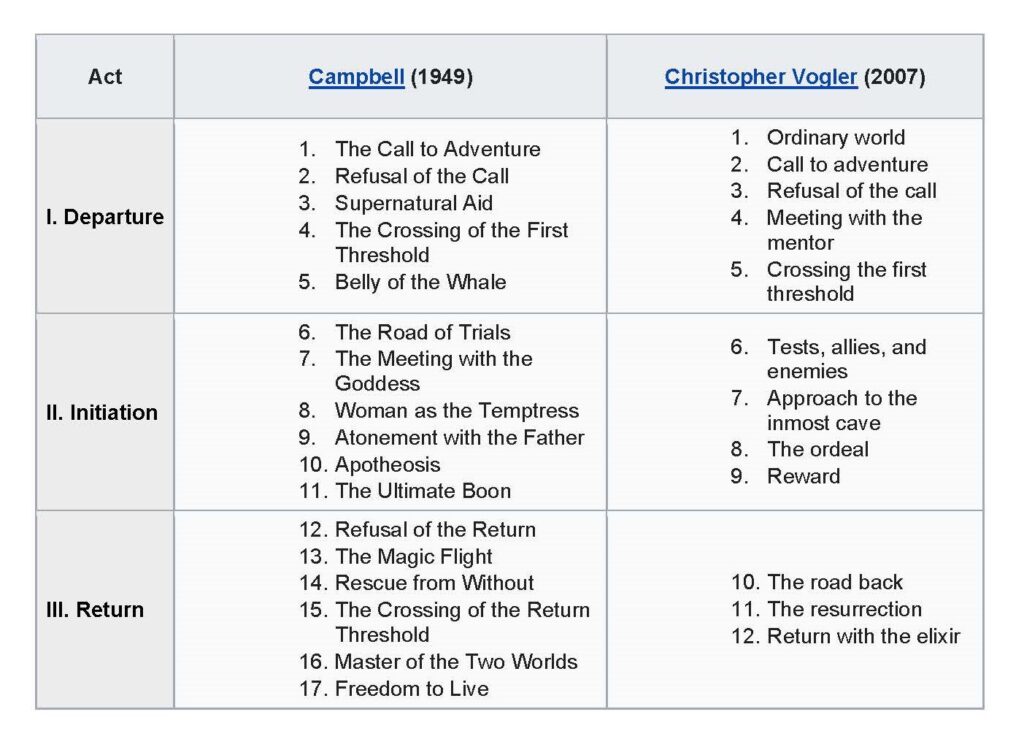

The Hero’s Journey has been a subject of study and discussion for many years. Two prominent formulations of the Hero’s Journey illustrate its influence on storytelling. One is the monomyth model set out in Joseph Campbell’s famous 1949 academic book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Campbell focused on synthesizing commonalities across the myths of numerous centuries and cultures; he sought to explain and understand stories told long ago, not to offer guidance for use by future storytellers. The other is the mythic structure model described by screenwriting and story consultant Christopher Vogler. Initially developed in a 1985 memo written for Disney studio executives, Vogler later expanded and elaborated his ideas into his book The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, recently republished in a 25th Anniversary Edition (fourth edition, 2020). George Lucas drew substantially on Campbell’s ideas, especially in crafting the story and screenplay for the first Star Wars film. Like Lucas, Vogler graduated from USC’s film school and began studying and analyzing stories in the late 1970s, and he praises A New Hope as a perfect encapsulation of Campbell’s model.

Both frameworks continue to heavily influence many contemporary storytellers. Campbell’s model has particular appeal to storytellers, like Lucas, who overtly wish to create stories with mythic themes and resonance with legends of the past. Vogler, on the other hand, sought to identify the underlying story structure which propels successful modern stories, particularly movies, and he illustrates the applicability of his model not only with mythical tales like The Wizard of Oz or The Lion King but also films as wide-ranging as Titanic, Pulp Fiction, The Full Monty, Beverly Hills Cop, and An Officer and a Gentleman. Campbell’s model divides the hero’s path into three phases based upon the patterns synthesized from historical myths; Vogler’s model is based on the three-act structure which dominates modern movie-making. While the two Hero’s Journey models have many similarities, they also have some significant differences.

Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth

The story begins in the hero’s mundane world. Often they are bored, yearning for something more exciting in their life. At the beginning of A New Hope Luke Skywalker is a moisture farmer on Tatooine, for example, while in The Force Awakens Rey’s daily routine consists of scavenging parts from starship wreckage and trading them for food.

Soon, though, that mundane existence is disrupted by the Call to Adventure. Luke unlocks Leia’s hologram plea while cleaning R2-D2. In The Mandalorian Din Djarin, who thinks he is undertaking yet another ordinary bounty, discovers The Child in a pram.

But the hero usually is not committed to the heroic path immediately, instead manifesting a Refusal of the Call as a desire to remain in the mundane world. Luke tells Old Ben that he can’t leave to go to Alderaan and learn the ways of the Jedi, but must instead stay and help with the farm. Rey needs to stay on Jakku to wait for her family. Din hands off The Child to the Imperials and takes his payment.

Frequently, but not always, the hero receives Supernatural Aid before the point that they truly commit to undertaking their journey. For Luke in A New Hope, it is the classic mentor figure of a wizard with magical powers: Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi providing the first brief lessons about Luke’s father, the Jedi, and the Force. The script is flipped in The Mandalorian, with the otherwise helpless Child saving Din from the mudhorn with the Force. Often this stage involves the hero receiving a talisman that will aid their quest, such as Obi-Wan giving Luke his father’s lightsaber or Han Solo giving Rey a silver blaster upon their arrival at Takodana.

The moment when the hero leaves the mundane world behind and enters the field of adventure marks The Crossing of the First Threshold. Obi-Wan takes Luke to the hive of scum and villainy, Mos Eisley, where they secure passage off planet from Han Solo and Chewbacca. Din forcibly extracts The Child from the Imperial facility, breaking his code with the Bounty Hunter Guild and accepting the consequences the act will bring.

Part of the separation from the mundane world involves a process of metamorphosis into a hero, which Campbell calls The Belly of the Whale. In The Force Awakens, the imagery is quite literal: Han’s gargantuan freighter swallows up the Falcon much like familiar imagery of Jonah and the whale. In A New Hope the near-death experience in the trash compactor aboard the Death Star serves this role in Luke’s story.

At this point the first phase of Campbell’s model, the Departure, has come to an end. The next phase, the Initiation, has begun.

Developing into a hero does not come easily. The Road of Trials repeatedly tests the hero, and the hero typically fails one or more of them. In most stories, this stage is the longest part of the tale, covering most of the time from the entry into the world of adventure until the climactic events of heroism at the quest’s culmination. In A New Hope, for example, it spans from Mos Eisley to the trench runs on the Death Star. Based on the male-protagonist focus of the historical myths he studied and the commonalities they frequently involved, Campbell’s model uses gendered labels to identify several common stages within the hero’s trials. One is The Meeting With the Goddess, when the hero encounters a source of unconditional love and inspiration that motivates the hero to continue the quest with a promise of a desired reward at its end. In The Force Awakens, Rey does not initially accept the unconditional love from the Force that Maz Kanata opens to her in the catacombs on Takodana, but the memory of Maz’s words later guides Rey to find serenity and strength in the Force during her forest duel with Kylo Ren. By contrast, Woman as Temptress offers the hero a temptation to abandon the quest; in modern stories, fortunately, that temptation can take many forms. In The Mandalorian, Omera presents Din Djarin with the alluring idea of settling down to a domestic life in a small village on Sorgan rather than continuing his dangerous quest to return The Child to his people; in Obi-Wan Kenobi, the revelation that Darth Vader is still alive diverts Obi-Wan from his primary mission to safely return Leia to Alderaan. Finally, The Atonement With the Father denotes a confrontation with a figure of ultimate power whom the hero must overcome. Viewing The Empire Strikes Back as the middle segment of a three-movie Hero’s Journey, this stage is famously literal for Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader. In The Hunger Games, Katniss encounters President Snow before she enters the Games; in the Captain Marvel film, Carol must break free of the manipulations of the Supreme Intelligence before she can unleash her true self, both emotionally and with her superpowers.

The culmination of Campbell’s second phase occurs when the hero accomplishes the goal of the quest. The hero’s Apotheosis reflects a literal or metaphorical death or attainment of a state of divine knowledge or bliss. Luke in A New Hope turns off his targeting computer and trusts in the Force for the fateful torpedo shot.

The hero’s triumph is The Ultimate Boon, when the purpose of the adventure is fulfilled. Luke destroys the Death Star, saving Leia, the Rebellion, and the galaxy from the Empire’s terrible planet-killing weapon.

The successful accomplishment of the quest is not the end of the story in Campbell’s model, however. In the third phase, the Return, the hero must internalize the lessons learned on the adventure and reintegrate back into the mundane world. This phase could be extensive in historical myths; many modern tales, particularly movies, keep it very short or omit it entirely. (As seen below, Vogler’s model acknowledges this contemporary phenomenon by reducing this notion to a single step, rather than an entire phase of the journey.)

The Refusal of the Return is parallel to the Refusal of the Call at the story’s start: just as the hero was reluctant to leave the mundane world to undertake the adventure, now the hero is reluctant to leave the adventure behind and return to a regular life. As with the start of the quest, the hero frequently is assisted by means of The Magic Flight and a Rescue From Without that facilitate or enable the return. In The Force Awakens, for example, Rey does not make every effort to escape the planet’s death-throes after overpowering Kylo Ren in their duel at Starkiller Base. Rather, she runs to Finn’s side and cries over his unconscious form, apparently willing to accept her own death along with his – until Chewbacca arrives in the Millennium Falcon, beams shining down into the darkened forest like the light of a guardian angel, and the three of them escape for their return to the Resistance base.

Reaching the mundane world again often is not easy for the hero. Again paralleling the start of the quest, The Crossing of the Return Threshold signifies the hero’s acceptance of the necessity to reintegrate into everyday life after epic quests. The hero becomes the Master of Two Worlds by synthesizing both the heroic and the mundane in their existence. Finally, the hero achieves the Freedom to Live by rejecting the fear of death or regrets about the past. By Return of the Jedi, Luke has synthesized Jedi training and his love for his friends and his family into a singular, rather than dual, sense of self. In the final showdown on the second Death Star, Luke is unafraid of his own death and accepting of his father’s past when, as “a Jedi, like my father before me,” he tosses aside his lightsaber and rejects the dark side.

Christopher Vogler’s Mythic Structure

Although Vogler’s model, like Campbell’s, has three major segments, the two frameworks break out those divisions within the story quite differently. Accordingly, while the initial stages appear very similar, the later elements vary significantly. In addition, Vogler incorporates common character archetypes that play iconic roles in the Hero’s Journey.

Act One unfolds in Vogler’s model very similarly to Campbell’s. The story of the Hero begins in The Ordinary World. The Call to Adventure (Inciting Incident) typically occurs through an encounter with a Herald who literally or metaphorically sounds the call. The motivation for the Refusal of the Call (The Reluctant Hero) can be personified in the Threshold Guardian, usually a person or entity seeking to keep the hero in the ordinary world. (A classic example is Uncle Owen in A New Hope, who insists Luke must stay and help with the farm instead of enrolling in the Academy, and to whom Luke’s sense of obligation not to run off to Alderaan is owed.) But the hero also will be Meeting the Mentor, who not only provides impetus to begin the quest but also guides the hero along the way. Crossing the First Threshold marks the point when the hero leaves the ordinary world behind and enters the extraordinary world of the adventure or quest.

Although these story beats and archetypes are familiar, they can be used by creative storytellers in new and unexpected ways. In the Obi-Wan Kenobi series, for example, the titular character is the Hero and his Ordinary World is his period of exile on Tatooine. The Herald is Bail Organa, who delivers the Call to Adventure first by holocomm and then in person. The Threshold Guardian is Luke, because even though Obi-Wan at this point has never spoken to the boy, his sense of duty to safeguard his ward is so great that he does not believe he can leave Tatooine even for the urgent need to rescue Luke’s kidnapped twin sister. “She is as important as he is,” Bail admonishes Obi-Wan, and Kenobi leaves Tatooine to head to Daiyu to rescue her. Though Obi-Wan is the mentor to Luke in A New Hope, in Obi-Wan Kenobi he is the Hero and Leia is his Mentor. Through their time together it is Leia who, albeit unknowingly, leads Obi-Wan through his spiritual journey to recover the long-buried Jedi Master within. The Obi-Wan Kenobi series makes the Skywalker twins equally important to Obi-Wan’s journey in their own ways.

Act Two in Vogler’s model also incorporates an extended stage of Tests, Enemies, and Allies that mirrors Campbell’s Road of Trials. This stage involves a set of experiences through which the hero learns the rules of the Special World and faces challenges that must be overcome. Some of the Tests will be failed, especially early on. The other characters the Hero encounters often fit into Vogler’s archetypes. An Ally is typically the most straightforward, providing assistance to the Hero on their adventure. Enemies can include dangerous villains, underlings or minions to defeat or bypass, or monsters that block the Hero’s path. The Shadow, though, is more than an obstacle or adversary, but rather the antagonist who poses the greatest emotional or spiritual challenge to the Hero because they are inversions of the Hero and can exploit their biggest psychological weaknesses. (A classic example is Darth Vader as Luke’s Shadow in the Original Trilogy. Similarly, Kylo Ren functions as Rey’s Shadow for most of the Sequel Trilogy.) The archetype of the Shapeshifter fits characters whom the Hero struggles to understand, often because their loyalties or allegiances are unclear to the Hero. The Trickster, by contrast, may actually have changing loyalties, or simply be an opportunist out for themselves. (In both Norse mythology and the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Loki is the classic Trickster. When he serves as the protagonist of the Disney+ Loki series, the Variant named Sylvie takes on the Trickster role in the story.) Multiple instances of archetypes may appear in the story, although usually we find only one Shadow for each Hero.

In the Obi-Wan Kenobi series, the stage of Tests, Enemies, and Allies spans the adventure from Daiyu and Mapuzo to the Fortress Inquisitorius and Jabiim. During these episodes, Haja is a Trickster, Tala is a Shapeshifter (then an Ally), and Roken is an Ally. Though they interact only briefly until the finale, Vader is Obi-Wan’s Shadow throughout. Reva is the principal antagonist and an Enemy for much of Act Two. Her role alters to a Shapeshifter, however, once Obi-Wan discovers her true motivations toward Vader in their conversation during the siege of the Path base on Jabiim, setting up her change of heart on Tatooine in the finale.

The remaining stages of Vogler’s Act Two mark the start of his major divergence from Campbell. The Approach to the Inmost Cave brings the hero to the second threshold in the story, often the enemy headquarters or the most dangerous place in the Special World. In A New Hope, the Falcon is drawn into the Death Star. In The Force Awakens, Rey is held prisoner at Starkiller Base.

Soon the hero must endure an Ordeal, a point where the hero’s fortunes are at their worst and the audience fears the hero may die, or even believes they do die, only to experience exhilaration when the hero somehow survives. In A New Hope, this is marked by the famous trash compactor sequence, when Luke is nearly drowned by the dianoga before being suddenly freed as the walls begin to close. In The Force Awakens, Rey is brutally interrogated by Kylo Ren. In Obi-Wan Kenobi, the refugees on the Path will be captured or massacred by the Empire on Jabiim unless Obi-Wan can find a way to outsmart and outmaneuver first Reva and then Vader.

After surviving the Ordeal, the hero can claim the Reward (Seizing the Sword) of the quest. This can mean obtaining a physical treasure, or a more metaphorical prize such as knowledge or experience the hero needs. In A New Hope, Luke rescues Leia from the Empire’s prison and the Rebels escape the Death Star with the plans that are key to its destruction.

Act Three of Vogler’s model is not about winding down the adventure, as in Campbell’s monomyth, but rather about driving the story onward to its climactic conclusion. By surviving the Ordeal and obtaining the Reward, the hero has only made the adversaries more insistent upon defeating them.

The hero is often pursued ruthlessly on The Road Back, and Vogler notes that some of the best chase sequences in movies occur at this point the story as the villain’s forces try to stop the hero from getting away with the Reward or otherwise escaping their clutches. While the destruction of the TIE fighters to escape the Death Star and reach the Rebel base at Yavin is a fairly short sequence in A New Hope, Rey’s road back is more extensive in The Force Awakens, spanning from her escape from the prison cell until Kylo Ren blocks her way in the forest.

The journey reaches its apex in the Resurrection (Climax) of the story. Vogler describes this as the villain’s last shot before being defeated, often a second life-or-death moment for the hero in addition to the Ordeal. It is the third threshold on the journey, the hero’s final test in which the lessons learned must be brought to bear to succeed. In A New Hope, the trench run is going very poorly for the Rebels, and it appears Luke is about to be killed by Darth Vader when Han’s unexpected return saves him at the last moment; Luke then listens to the ghostly wisdom of his mentor, closes his eyes, and fires the torpedoes that destroy the Death Star. In The Force Awakens, Rey duels Kylo Ren in the forest. In Obi-Wan Kenobi, dueling Vader on a desolate moon, Obi-Wan strikes the pose he used against General Grievous on Utapau in Revenge of the Sith, signifying that Jedi Master Kenobi has found himself once more.

The final stage of Vogler’s model is the Return With the Elixir (Denouement), in which the hero’s triumph is shown. In A New Hope, Luke has destroyed the Death Star, Darth Vader is defeated, and Luke receives a medal of heroism from the Rebellion. In Obi-Wan Kenobi, Leia is returned to her parents on Alderaan and Obi-Wan has made peace with his emotions toward both Anakin and Luke so that going forward he is neither dwelling on the tragedies of the past nor consumed by fear of what could go wrong in the present.

Vogler notes that an Epilogue can be an effective technique to look ahead from the main ending of the story. Often, the purpose of the epilogue is showing how events turned out for the characters in the future, as in American Graffiti, Terms of Endearment, or A League of Their Own. In The Force Awakens, by contrast, the epilogue is not an additional cathartic element of the ending, but rather a cliffhanger that promises the audience that the film’s MacGuffin, the absent Luke Skywalker, will play a major role in the next film.

What About a Heroine’s Journey?

Compared to a decade ago, when FANgirl Blog began writing about the Heroine’s Journey, movies and television are offering considerably more stories with female protagonists. Some of them, of course, are not the kinds of tales suited for the monomyth or “origin story” structure. Among those with more traditional story formats, particularly when written by men, the protagonist’s arc tends to bear a strong resemblance to Campbell or Vogler and the (male protagonist) Hero’s Journey.

While alternatives exist, contemporary storytelling has attained no consensus on a distinct Heroine’s Journey. Maureen Murdock’s 1990 book The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness is, like Campbell, a work intended for a professional field (in Murdock’s case, psychotherapy) rather than a guide for storytellers. Victoria Lynn Schmidt’s 2001 book 45 Master Characters is a writer’s guide, but contains only a short chapter on the Feminine Journey (and, separately, on the Masculine Journey), unlike Vogler’s lengthy volume. Additional scholars and commentators have suggested different variations. Others reject the notion of a Heroine’s Journey as conceding to gender essentialism, instead favoring storytelling principles that directly facilitate the inclusion of non-binary and LGBTQ+ identities. Harvard professor Maria Tatar’s 2021 book The Heroine With 1001 Faces is an incisive response to Campbell and a masterful exploration of the many strong and meaningful female characters found in fairy tales rather than in myths, but she aspires to inspire creators to revisit different source material rather than to propose a broadly applicable character model or story structure.

Although a Heroine’s Journey model has not solidified, it is still possible to identify some notable commonalities among prominent stories with female leads. In many of them, for example, the heroine is a nurturing hero as distinct from a conquering hero, prevailing through love or compassion rather than combat. (For that reason, some scholars contend that Luke Skywalker and Harry Potter are better understood as demonstrating a heroine’s archetype of heroism, especially at the culmination of their adventures, rather than as examples of traditional masculine heroism.) Similarly, in many of these stories the heroine’s romantic love serves as a source of strength to pursue her quest, rather than as a distraction from it (as in Campbell). Another important feature of many prominent Heroine’s Journey arcs is a loyal team of allies who assist and support the heroine in her success: the Scooby Gang across seven season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Team Katniss in The Hunger Games book and movie trilogies, Team Avatar in the four seasons of The Legend of Korra, Peggy’s group of allies in Agent Carter and Kara’s friends and allies in Supergirl, among others. Over time, perhaps some or all of these will become consistent elements of new Heroine’s Journey stories.

In April 2012, FANgirl Blog published the post The Heroine’s Journey: How Campbell’s Model Doesn’t Fit, which became the most-viewed post on the blog. It later was selected for inclusion in The Bedford Book of Genres, a college composition textbook published by St. Martin’s Press, as a model example of persuasive blog writing. Although Campbell’s model still doesn’t fit, the Heroine’s Journey remains a work in progress.

.

(Some passages and descriptions above are derived from Rey’s Heroic Journey in The Force Awakens, first published at FANgirl Blog on February 8, 2016.)

.

The Hero’s Journey at FANgirl Blog

- Rey’s Heroic Journey in The Force Awakens (Jan. 2016)

- Finn and the Hero’s Journey in The Force Awakens (July 2017)

- The Last Jedi and the Hero’s Journey – Part One: Rey (Jan. 2018)

- The Last Jedi and the Hero’s Journey – Part Two: Finn (Jan. 2018)

- The Last Jedi and the Hero’s Journey – Part Three: Luke Skywalker and the Wizard’s Journey (Jan. 2018)

- The Last Jedi and the Hero’s Journey – Part Four: Kylo Ren and the Villain’s Journey (Feb. 2018)

- The Hero’s Journey for Han in Solo (July 2018)

- Mastering Two Worlds: Concluding Rey’s Hero’s Journey in The Rise of Skywalker (Jan. 2020)

- Rey Deserved Better: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 1 (Jan. 2020)

- Obi-Wan Kenobi: Expanding the Monomyth (May 2022)

- Obi-Wan Kenobi: Jedi Master’s Trials (June 2022)

- Obi-Wan Kenobi: Master of Two Worlds (July 2022)

The Heroine’s Journey at FANgirl Blog

- The Heroine’s Journey: Defining Concepts (Mar. 2012)

- Team Katniss: Collaborative Success in The Hunger Games (Mar. 2012)

- Journey of a Strong Female Heroine: Katniss Everdeen (Mar. 2012)

- The Heroine’s Journey: How Campbell’s Model Doesn’t Fit (Apr. 2012)

- Legend of a Strong Female Heroine: Korra’s Journey (July 2013)

- GeekGirlCon 2014: Heroine’s Journey Panel Recap (Oct. 2014)

- GeekGirlCon 2015: Heroine’s Journey Panel Recap (Nov. 2015)

- GeekGirlCon 2016: Heroine’s Journey Panel Recap (Nov. 2016)

- The Heroine’s Journey in Supergirl (CBS/CW Television) (Nov. 2016)

- The Heroine’s Journey in Wonder Woman (2017 film) (June 2017)

- The Heroine’s Journey in Captain Marvel (2019 film) (June 2019)

- Diana’s Heroine’s Journey Continues in Wonder Woman 1984 (Jan. 2021)

.

last updated Sep. 10, 2022