Adapting a popular book to the big screen is always a challenge, particularly because changes and omissions are a necessity in condensing several hundred pages of prose – an afternoon’s or a day’s read, or longer, depending on the reader – into about two hours. In recent years, though, both the Harry Potter and Twilight series have proven that fans are more than willing to spend big dollars on book adaptations despite those differences, at least so long as the movie successfully captures the spirit of the books and the core elements of the story and its characters.

Adapting a popular book to the big screen is always a challenge, particularly because changes and omissions are a necessity in condensing several hundred pages of prose – an afternoon’s or a day’s read, or longer, depending on the reader – into about two hours. In recent years, though, both the Harry Potter and Twilight series have proven that fans are more than willing to spend big dollars on book adaptations despite those differences, at least so long as the movie successfully captures the spirit of the books and the core elements of the story and its characters.

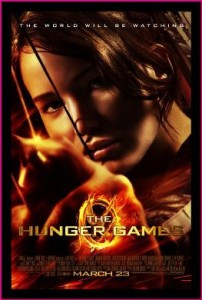

The Hunger Games, the first movie in the saga of Katniss Everdeen, may very well be the best book adaptation in a long time. Visually and tonally, it masters the spirit of the books: the poverty and hopelessness of District 12, the blissfully ignorant luxuriousness of the Capitol, the sickening spectacle of a televised teenaged death match, and the power of one person to stand up and make a difference. The plotline is streamlined, as it has to be, and some of the minor characters and world-building explanations fall by the wayside. The movie declines to rely on voiceover narration to mimic Katniss’ internal monologue from the book, instead using dialogue, visuals, and cutaways to brand-new scenes for the necessary exposition. Similarly, the large number of memory-laden flashbacks in the book are reduced to just two – the moment when Peeta throws Katniss the burned bread, and a hallucination-driven recollection of her father – and real-time cutaways are used to keep Gale in the audience’s mind, as he is in Katniss’ too.

The acting exceeds expectations, bringing the characters to life just as vividly as on the page. Jennifer Lawrence as Katniss is remarkable, and her performance stretches from nurturing to bold, afraid to angry, desperate to confused. Katniss experiences practically every emotional imaginable over the course of the story, and all of it is writ large on Lawrence’s face. Josh Hutcherson as Peeta conveys the earnestness and courage of the character beautifully, and Liam Hemsworth as Gale show tremendous skill at conveying so much meaning with just a small gesture or brief glance. Among the supporting cast, Woody Harrelson as Haymitch stands out, wonderfully walking the character through an arc from drunken fatalism to bemused curiosity to persistent dedication to his mentees. Donald Sutherland plays President Snow as a deliciously understated villain; there is no cackling laugh or twirled moustache, but only the calm incisive patience of a calculating tyrant. Impressively and disturbingly at the same time, Alexander Ludwig and Isabelle Fuhrman are positively chilling as Cato and Clove, the District 2 tributes absolutely committed to the bloodthirsty viciousness of the Games – a stark contrast to Peeta, whose greatest fear is not death, but selling out to become the mindless monster the Capitol wants him to be. And Lenny Kravitz, too, proves why he was an inspired choice for the quiet yet influential Cinna.

Director Gary Ross made a great storytelling choice to allow his actors to show the human side of the characters and the weaknesses even in courageous heroes. At times Katniss is proud, brave, and even brash. But Lawrence does not hesitate to unleash wide-eyed panic, wincing in excruciating pain, or fist-pounding fury. At multiple points in the movie Katniss is literally trembling, and neither Ross or Lawrence flinches at its emotional impact. Similarly, though Gale’s limited role showcases his stoic strength, Peeta’s strength comes from wearing his heart on his sleeve, whether a humble admission of his lifelong crush on Katniss, tears of pain, or his willingness to sacrifice himself to save her. Together, Katniss and Peeta win the Games – and each of them openly cries onscreen. Too often, in movies and real life, the message seems to be that heroes cannot show weakness or admit suffering, and it is refreshing to be reminded that it doesn’t have to be that way.

In part, The Hunger Games is an allegory about the toxic combination of reality television twisted into political propaganda. In the book, these themes are revealed solely through the eyes of a sixteen-year-old girl as she experiences the Reaping, the preparations and training, the Games, and the consequences of her victory. By the very nature of telling the story that way, Katniss is often unaware of the full extent of events around her. In the movie, Ross breaks out of exclusively Katniss’ perspective, and it enables the allegory to take a much larger, more powerful presence in the story. Certain aspects are lost without Katniss’ internal monologue, but the politics of Panem are shown much more clearly – which no doubt will pay big dividends in the subsequent films as open rebellion against the Capitol unfolds.

Ross uses a particularly interesting mix of camera styles to subtly weave Katniss’ point of view with the external allegory. The movie begins with shaky, handheld cameras as we experience the initial reality of Katniss’ life in District 12, and then the Reaping. The moment she steps aboard the train to the Capitol, though, the camera quickly stabilizes and comes into sharp focus – the moment we begin watching her life unfold on television, instead of through her own eyes. Ross then returns to the close, shaky perspective for parts of the Games when the audience needs to be right there with Katniss, such as the opening bloodbath at the Cornucopia, her flight from the forest fire, and the trackerjacker hallucinations. For much of the Games, though, we are watching Katniss from afar with stable cameras – just like the audience in the Capitol.

The Hunger Games has too many great little moments to list them all, but these are a few of my favorites:

- The thirty-second countdown prior to the start of the Games, when Katniss has to walk away from Cinna and get into the tube to the arena, was brilliantly acted and filmed.

- The series of quick cutaways to Gale back in District 12 were very effective not only at keeping him present in the story, but also in revealing his character. At first, he cannot bring himself to watch the opening bloodbath, and perhaps too he is recalling some of his last words to Katniss, wondering what would happen if no one watched. Later, though, he does watch her in the Games, his expressions a mix of confidence, worry, and maybe a twinge of jealousy.

- The brand-new scenes with Snow and Seneca discussing the political function of the Games in Panem, and with Caesar and Claudius blathering on about the competition as though it is just some ordinary athletic tournament, make powerful additions to the story. They really drive home just how corrupt and twisted the Capitol has become.

- At several points Katniss looks directly into camera, and Ross uses the moment as a transition to another place, such as the Gamesmakers’ control room or the riot in District 11. The riots, and also the reactions of the controllers to Katniss, most powerfully reveal her impact on others while the heroine simply is invested in fighting to stay alive.

- In the train car, Haymitch pins Peeta to his chair with a bare foot. He may be a drunk with little hope for his new mentees at that point – but it shows the spark within him that allowed him to win the Games years earlier, and inspires him to become their assist from the outside on the path to victory.

Like any movie, of course, The Hunger Games is not perfect. For example, several relatively substantial components of the world-building of Panem – including the tesserae, the distribution of resource production among the Districts, and the legend of the supposedly destroyed District 13 – are referenced so obliquely that they will probably be missed by most viewers who haven’t read the books. Perhaps the most noticeable weakness in the film, though, especially coming from a Star Wars background, is that the special effects are disappointingly underwhelming. The expansive establishing shots of the Capitol do not have obvious flaws, but it’s clear they were kept brief in favor of physical sets and costumes. The flames on the two Girl on Fire outfits were meant to be visibly fake to the audiences in the Capitol, and yet they seemed incongruously unimpressive compared to all the high technology on display in and around the Games. The muttations at the end, though, were by far the weak point in the special effects – they were clearly computer-generated, and stuck out as such even amid the dark night of their scenes. If the Gamesmakers’ control room had seemed less advanced, then perhaps the insufficiently realistic-looking muttations would have fit in better. Instead, it breaks the immersion for the audience when it should be reinforcing it. In a movie sparse on special effects overall, these few weak points are not a significant defect. Still, Lionsgate might have been better served spending a few million dollars more for top-notch special effects in what was already a big-budget film.

The Hunger Games more than does justice to the book – it creates a visual, aural, and musical representation of the story that is emotionally powerful in its own right. It is a movie worth seeing again and again.

9/10