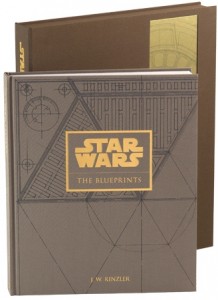

Weighing over twenty-five pounds, Star Wars: The Blueprints is literally a hefty new addition to the line of nonfiction coffee-table books that give fans behind-the-scenes glimpses at the creative process of the Star Wars films. Lucasfilm’s master of its real-world Jedi Archives, author J.W. Rinzler previously wrote the highly regarded The Making of Star Wars and The Making of The Empire Strikes Back, and is currently researching the companion volume for Return of the Jedi; those books chronicle the travails and triumphs of the films from script and preproduction through casting, filming, post-production, and theatrical release. The concept art for everything from characters, creatures, and costumes to locations and vehicles for each of the six Star Wars films also have been featured in their respective Art of… books.

Weighing over twenty-five pounds, Star Wars: The Blueprints is literally a hefty new addition to the line of nonfiction coffee-table books that give fans behind-the-scenes glimpses at the creative process of the Star Wars films. Lucasfilm’s master of its real-world Jedi Archives, author J.W. Rinzler previously wrote the highly regarded The Making of Star Wars and The Making of The Empire Strikes Back, and is currently researching the companion volume for Return of the Jedi; those books chronicle the travails and triumphs of the films from script and preproduction through casting, filming, post-production, and theatrical release. The concept art for everything from characters, creatures, and costumes to locations and vehicles for each of the six Star Wars films also have been featured in their respective Art of… books.

As Rinzler explains in his Introduction (p10), The Blueprints provides an in-depth look at a stage of the creative process rarely seen previously by the public: the technical drawings from the production design department. The work of this team was critical to the filmmakers’ success, giving them detailed schematics for indoor and outdoor sets, the interior and exterior of starships and landside vehicles, and smaller but no less carefully sketched items like set dressing and droid bodies. So much of what fans can immediately identify visually – the Millennium Falcon and an X-wing, the Death Star and Jabba’s palace and sail barge, R2-D2 and an AT-AT, a Star Destroyer bridge and the corridors of Cloud City – could only be brought into existence because the production design department drafted the drawings necessary to construct them. Why, then, has this important contribution received such little attention for so long? Rinzler surmises that the rapid pace at which the movies were filmed in the studios played a major role (p10): one set would be built, its scenes shot, and then that set immediately torn down and the next set for different scenes built anew in the same space; unlike the concept art and many of the costumes and props, the sets did not survive their days of filming, much less the end of photography. With those iconic locations of the Star Wars films gone forever, The Blueprints gives fans an invaluable peek at how the galaxy far, far away was built.

The technical drawings are fascinating to study, but what makes The Blueprints truly great is that Rinzler has taken care to ensure the book is as much the story of the men and women of the production design department as it is a presentation of their craft. From start to finish, the prose accompanying the drawings relates the words of mentors and mentees, the bonds among the draftspersons, and the relationships with other aspects of the production. We’ve often heard that the production teams on the Star Wars films became like a big family, and that dynamic leaps off the page in The Blueprints, too. Young draftsmen rise through the ranks as the movies progress, and some even end up working on the prequels, including Gavin Bocquet, the lead production designer. The team also clearly has the deepest respect for one another, such as Peter Russell’s praise of the late Fred Hole (p310): “He could make a toilet seat look good.” Perhaps most impressive, though, is Rinzler’s remark that the production designers on Star Wars went on to dominate the industry for thirty years (p11), working successively on Star Wars, Alien, Superman, The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Return of the Jedi.

Other topics also weave throughout the books’ prose. One recurring theme is the constant pressure to keep the movies within budget, and the creative ways the production designers used their technical diagrams to reuse sets, take advantage of camera angles and other visual tricks, and save money by designing partial sets instead of full ones. Another constant, naturally, is the presence of George Lucas and his interaction with the production designers. Their mutual respect is apparent, perhaps nowhere more clearly than in George Lucas’ declaration, after the many frustrations of principal photography and a film coming in over budget (p91), that: “I would rate the production design department the highest of the whole film.” Last but certainly not least, in the technical drawings and the prose, is the amazing attention to detail of the designers. Notations are abundant, from cross-references to other drawings or art department materials to specifying which drawings are not-to-scale. With hundreds of drawings for each of the original trilogy movies, the effort is remarkable.

Other topics also weave throughout the books’ prose. One recurring theme is the constant pressure to keep the movies within budget, and the creative ways the production designers used their technical diagrams to reuse sets, take advantage of camera angles and other visual tricks, and save money by designing partial sets instead of full ones. Another constant, naturally, is the presence of George Lucas and his interaction with the production designers. Their mutual respect is apparent, perhaps nowhere more clearly than in George Lucas’ declaration, after the many frustrations of principal photography and a film coming in over budget (p91), that: “I would rate the production design department the highest of the whole film.” Last but certainly not least, in the technical drawings and the prose, is the amazing attention to detail of the designers. Notations are abundant, from cross-references to other drawings or art department materials to specifying which drawings are not-to-scale. With hundreds of drawings for each of the original trilogy movies, the effort is remarkable.

There are so many great technical drawings in The Blueprints, it’s impossible to pick favorites. Some of the highlights, though, include: the famous starships, including the Falcon, X-wings, and TIE Fighters; the droids, especially R2-D2 and C-3PO; the interior floorplans of locations like the Tatooine moisture farm and cantina and the Death Stars; and maps of exterior locations such as Yoda’s enclave on Dagobah and the shield generator bunker on the Endor moon. A real treat is the very first technical drawing for Star Wars, a moisture vaporator drawn on November 26, 1975, by Peter Childs (p36). Other fun elements include discussions of how technical drawings enabled the crew to film some of the dusty Mos Eisley alleys in England instead of Tunisia (p50), and the designers discussing the different drawing styles between American and British draftsmen (p63).

About eighty percent of The Blueprints is dedicated to the original trilogy, but the section on the prequel trilogy certainly has its share of insights. Rinzler starts off by rebutting the conventional wisdom that the prequels were all CGI, noting that, among other things, the production team included a carpentry shop the size of a football field (p272). Even Episode III, with the most CGI of the prequels and filmed digitally, still had an entire room of the production devoted to blueprints, many of which were drawn using CAD (computer-aided drafting) rather than by hand (p319). We learn that the technical drawings of Theed in The Phantom Menace were drawn in June 1997, and the sets were built to twenty or twenty-five feet in height, with the rest above that filled in with CGI. Nine of the Podracers were also built full-scale from the technical drawings. Similarly, the technical drawings enabled the Episode I crew to film the exterior of the Tatooine buildings on location in Tunisia, while the building interiors were filmed on sets in England. Rinzler also reveals that the production designers for Revenge of the Sith were forced to recreate new blueprints for the floorplan of the Organa family diplomatic vessel because the originals from the first movie could not be found – until Rinzler managed to locate them deep in the Lucasfilm Archives while researching The Blueprints, which reveals both sets of drawings for the first time (p330).

About eighty percent of The Blueprints is dedicated to the original trilogy, but the section on the prequel trilogy certainly has its share of insights. Rinzler starts off by rebutting the conventional wisdom that the prequels were all CGI, noting that, among other things, the production team included a carpentry shop the size of a football field (p272). Even Episode III, with the most CGI of the prequels and filmed digitally, still had an entire room of the production devoted to blueprints, many of which were drawn using CAD (computer-aided drafting) rather than by hand (p319). We learn that the technical drawings of Theed in The Phantom Menace were drawn in June 1997, and the sets were built to twenty or twenty-five feet in height, with the rest above that filled in with CGI. Nine of the Podracers were also built full-scale from the technical drawings. Similarly, the technical drawings enabled the Episode I crew to film the exterior of the Tatooine buildings on location in Tunisia, while the building interiors were filmed on sets in England. Rinzler also reveals that the production designers for Revenge of the Sith were forced to recreate new blueprints for the floorplan of the Organa family diplomatic vessel because the originals from the first movie could not be found – until Rinzler managed to locate them deep in the Lucasfilm Archives while researching The Blueprints, which reveals both sets of drawings for the first time (p330).

Printed by Epic Ink in an exclusive, limited-edition run of 5000 copies, The Blueprints features high production values well worth the price. The paper is thick and heavy, and the binding is carefully woven to hold the weight of the pages. The images are crisp and clear, even the oldest of the drawings. The Blueprints is an astounding book, and will be a pleasure to read and study for years to come.