Interview by Priya Chayya

Interview with Jill Lepore, author of The Secret History of Wonder Woman. For a more detailed look at the book, check out my review.

Note: Some responses are taken from the publisher’s Q&A provided by Knopf; used with permission.

Can you talk about the Wonder Woman of this book? I think many people who discovered her later or through the 1970s TV show will be surprised by the Wonder Woman depicted here.

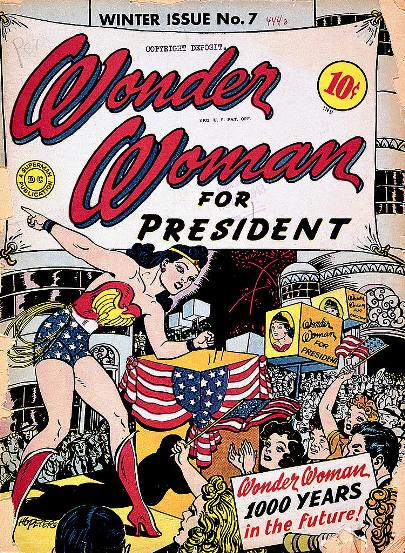

Wonder Woman is the most popular female comic-book superhero of all time. Aside from Superman and Batman, no other comic-book character has lasted as long. Superman started in 1938, Batman in 1939, Wonder Woman in 1941. She was created by Marston after he was hired by DC Comics, as a consulting psychologist, to help quiet critics of comic books; critics thought Superman looked like a fascist, and it was a real problem that, for a few months, Batman used a gun. Marston introduced a whole set of reforms at DC but he also thought the best way to address the comic-book controversy was to create a female superhero, to counter the comics hyper-masculine violence. Marston and the women he loved had been deeply influenced both by the suffrage movement and by the early feminist movement. The original Wonder Woman is in many ways truly radical. Superman owes a debt to science fiction, Batman to the hard-boiled detective. But Wonder Woman’s debt is to the feminist utopia and to the struggle for women’s rights. Her origins story is about leaving her home, among Amazons on Paradise Island–a story taken straight out of the writings of feminists like Charlotte Perkins Gilman–and coming to the United States to fight for equality to fight for women. It turns out that nearly everything interesting about Wonder Woman has been missed or overlooked or misunderstood, partly because a lot of what’s interesting has been kept secret, but partly because the people who write about the history of comic books don’t tend to be interested in the history of feminism.

Can you talk a bit about your research and what sources you discovered and accessed to that allowed you to tell this new story?

Most of my research was done in university archives, at the colleges where Marston, Olive Byrne and Marston’s wife Elizabeth Holloway, either studied or taught. They left behind an incredible paper trail. I also relied on the vast collections of Margaret Sanger’s Papers. I used a set of manuscripts that Marston’s widow left to the Smithsonian, in Washington, and another set of Wonder Woman materials housed in the archives of DC Comics, in New York. Essential to this project, though, was reading the private, unpublished papers of all these people, which remain in family hands. The Martsons were incredibly generous in letting me read diaries and letters and pore over photo albums. There were all kinds of unexpected treasures, too. I found the papers of two members of DC Comics’ Editorial Advisory Board, and was able to get to the bottom of the controversy over Wonder Woman in the 1940s. Marston created Wonder Woman to silence the critics of comic books; Wonder Woman proved, in the end, to be the most controversial comic-book character of all. IT was unbelievably fun to chase that story from archive to archive–opening boxes and boxes that, really, no one had ever opened before.

You write, “The Experimental Life of William Moulton Marston involved a great many things. He was willing to try anything.” Talk about a larger than life figure. It would be almost impossible to make him up. Did you know when you began this book what an intriguing person he would turn out to be?

Marston was endlessly fascinating. He was a scientist, a lawyer, an inventor, a filmmaker, a novelist, a therapist, and, last but not least, a comic-book writer. You can’t make this guy up. He had a hand in everything. People found him mesmerizing. Women, especially, found him mesmerizing. But I found the women the women in his life even more interesting, if more mysterious.

There is some pretty kinky stuff in Wonder Woman, the bondage, the boots, the gags. As you say, “Not an issue, and hardly a page, lacks a scene of bondage…and while it’s true that this same iconography holds a prominent place in feminist and suffrage cartoons…there’s more to it than that.” So what’s with the bondage?

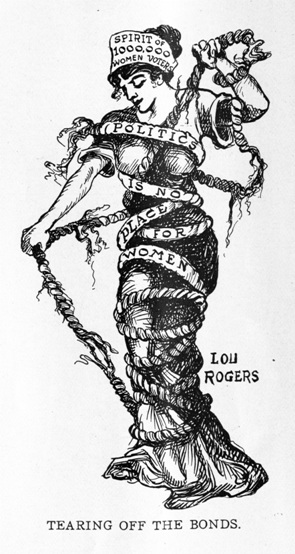

Chains, as symbols, were crucial to the suffrage, feminist, and birth-control movements. British suffragists chained themselves to the gates outside Downing Street. American suffragists chained themselves to the gates outside the White House. A woman dragging a ball and chain reading “unwanted babies” appeared on the cover of Sanger’s Birth Control Review, Sanger wrote a book called Motherhood in Bondage. Suffragists, feminists, and birth control activists wrote, all the time, about the ways in which women lived in a state of slavery and that political and legal reforms were necessary to secure their emancipation. When Marston created Wonder Woman, he had her tied up all the time, so that she could break free from her chains. This looked a lot kinkier to younger people than it did to people from Marston’s generation, who were used to this iconography. So that’s most of the story. But it’s also true that Marston was fascinated by chains and ropes and writes about them in lots of different places. And readers-grown men–wrote to him, about how much they liked all the bondage in Wonder Woman. Which is among the reasons that Wonder Woman is the most controversial comic-book character ever created.

What was the favorite thing you learned about Wonder Woman when writing this book?

My favorite thing was learning about the great feminist cartoonist Annie Lucasta Rogers, who published as Lou Rogers. She was amazingly prolific and influential in the 1910s and 1920s and had a big influence on Harry G. Peter, the artist who drew Wonder Woman. I loved looking at her work, and thinking about her life. She made me look at Wonder Woman completely differently.

What do you consider Wonder Woman’s greatest strength?

The strength I admire most is courage. When you’ve got superpowers, though, how much courage does it take to stand up for what’s right? Isn’t it harder to do that when you’ve got nothing more than ordinary, everyday powers? That said: the invisible plane. Because, of course: leg room.

With the recent announcement of a Wonder Woman movie being in the works, what is the one thing movie makers need to make sure shines through to keep her relevant?

I wonder if Wonder Woman being cast in a movie called Batman v. Superman, in 2014, isn’t maybe already too little too late …. But as for the stand-alone Wonder Woman movie, I think it’s got to be utterly different from other superhero movies, actually, since Wonder Woman’s origins have less to do with, say, the Justice Society than with the National Woman’s Party. It’ll sure be interesting to see.

Priya Chhaya is a historian who loves the written word. When she’s not reading anything she can get her hands on she is writing about the past and its intersection in our daily lives on her personal blog …this is what comes next.