WandaVision: Witch Way Is The Story Going?

WandaVision’s “All New Halloween Spooktacular” might have provided insight into the machinations outside of the Hex, but left fans feeling a little spooked about where things are going inside its titular characters. From a storytelling perspective, the sixth episode closes out the second act, bringing the protagonist to a defining point of conflict that upends the character’s world and leaves consequences that play out in the third act. In Captain America: Civil War, the second act concludes with the superhero clash at the Berlin airport, splitting the Avengers alliance and isolating Steve and Bucky in search of Zemo. Comparatively in this episode, Wanda locks the door on Goody Two Shoes Vision and blasts her trouble-making brother away as the episode winds down. She stops the world inside the Hex and then expands it, decimating the SWORD base and returning dying Vision to the protection of her magic-fueled reality. What will be the consequences of that action? The next episode, “Breaking the Fourth Wall,” reveals Wanda wallowing in depression, the fourth stage of grief.

One of the most perplexing pieces of Episode 6 was the Claymation commercial. Where other commercials appeared much more direct in their allusion to traumatic events in Wanda’s life, the shark and the boy on the island seemed obtuse. The fifth episode’s commercial referenced tragedy at Lagos, and on a superficial level the Yo-Magic ad stays with the events of Civil War. In its third act, Wanda and the other superheroes aligned with Captain America are incarcerated in the Raft, a prison at sea. She is bound and unable to reach her magic, striking direct parallels to the boy’s predicament as he tries to reach the magic yogurt and can’t. Notably, superhero movies are known for using trauma as a means to define villains – Zemo seeks revenge for his dead family, Thanos believes he can spare others from watching their worlds collapse. Trauma induces new trauma and becomes a cycle. The boy repeating the effort of opening the yogurt container but never accomplishing it parallels the residents of Westview on the periphery of the Hex, who are stuck in loops or even frozen in place. Many have noted how grim the commercial plays, but it comes on the heels of Vision walking down a cul-de-sac where the trick-or-treaters in the shot are skeletons, ghosts, and dead people and the house at the end of the street is adorned with a fanciful graveyard as decoration. The Claymation commercial may have a few other levels of symbolism, as well, but the important point is that it speaks to how much this episode leaned on the storytelling concept of meta: from dialogue to Halloween costumes, and even the holiday itself.

Have you ever been to a meeting about how to have better meetings? That’s meta. It’s often found in genre storytelling because the story itself can reference a vast history of canon. This is where Easter Eggs come from, sort of meta appetizers – and WandaVision uses them in a mixture of fan service, storytelling truths, and red herrings. But meta can be grander and provide deeper meaning, which is where the use of the Halloween holiday as a setting really takes it up a notch. The costumes worn by Wanda, Vision, and Agnes tell us truths about who the characters are – in addition to giving nods to the Marvel comics. Wanda’s Sokovian fortune teller harkens back to her roots, who she was before she became a superhero, and foreshadows who she will become: The Scarlet Witch. Vision wears the costume Wanda has allowed to exist, suggesting she is in control of his reality. Whereas Billy appears to be in touch with who he is, it’s not until after Pietro does a quick change with Tommy into the Quicksilver attire that the other twin discovers his speedy powers. Agnes, she has been a witch all along.

Beyond the basic meta of dressing the characters in costumes that reveal a character’s true identity, the holiday itself bears some exploration in a discussion about meta storytelling. Halloween in its present expression is a commercial holiday, where children put on costumes and venture out into the neighborhood asking for treats. “Halloween” is derivative of its connection to All Hallow’s Eve, a night in Christian observance that recognized the hallowed souls. As such holidays often are evolutions of older pagan celebrations, historians have found relation to the Roman and Celtic festivals that centered on the end of the harvesting season and the beginning of winter. For Wanda, Halloween marks the beginning of her emotional winter, which is denoted by Episode 7’s Nexus anti-depressant advertisement that indicates the fictional realm of Westview is finally catching up to Wanda’s trauma in real time. Interestingly too, the Celtic festival Samhain marked a time when the boundary between the ordinary world and the supernatural world was thinnest. In WandaVision “All New Halloween Spooktacular,” Vision escapes the Hex and Wanda is forced to fortify it. And one has to wonder if a witch might have known that Halloween was the best time to make a break for it?

This opposing blending of Christian and pagan themes starts to come into sharp focus in “Breaking the Fourth Wall,” and was inevitable for a story intent on being an allegory about Marvel’s strongest superhero taking the mantle of Scarlet Witch. Witch trials have resulted in the murder by execution of thousands of people, primarily women, over the centuries. The deadliest occurred in Salem, Massachusetts, between 1692 and 1693; at that point, witch trials had been ongoing for almost a half-century in colonial America. The trials were a result of mass hysteria fueled by religious extremism, family rivalry, and political squabbling. It was abject abuse of laws to maintain a patriarchal power structure. In fact, in our current culture it is understood to be such a foul moral act that politicians, often aligned with the extreme Christian right, use the term “witch hunt” when their own actions are called into question. Witch trials in essence are a generational trauma inflicted for the most part on women, making Wanda’s story of grief the perfect metatextual place to explore this concept.

Although witch hunts are deemed evil within our own laws and social contracts, the notion of witches as the embodiment of evil is sewn into the fabric of modern storytelling – from the Wizard of Oz’s Wicked Witch of the West and Star Wars: The Clone Wars’ Mother Talzin to Little Mermaid’s Ursula and Sleeping Beauty’s Maleficent. A notable swath of pop culture media has been willing to take WandaVision’s Agatha Harkness as the villain at face value without considering the more recent trend in storytelling to explore the subtext of witches as an expression of female trauma – from Wicked’s Elphaba and The Vampire Diaries’ Bonnie Bennett to the titular Disney live action Maleficent and Descendants series’ Mal and Uma. While Wanda’s trauma is front and center in WandaVision after taking a backseat in the overarching narrative of the male-centric Avengers Marvel Cinematic Universe run, the signs of Agnes’ trauma – absentee husband, fondness for liquor, and shunning by her neighbors – have been peppered throughout the series similarly to the clues that she is a witch.

It’s been interesting to watch how WandaVision “Breaking the Fourth Wall” operates on the conceit that Wanda is letting us into her life like a documentary film. The show even breaks the illusion of the documentary when a voice off-screen asks Wanda if she believes she deserves her life circumstances. This is where an understanding of the history of witch trials becomes as critical to examining WandaVision as comic book lore and supernatural fiction. The Salem Witch Trials were initiated when three girls were afflicted with mysterious symptoms, speaking in gibberish and bizarre fits. The father of two of the girls, a reverend, consulted with a doctor, who determined they were afflicted with witchcraft. The witch hunt led to accusations against three women: an enslaved woman, a poor woman, and an older woman scorned for defying social norms. The enslaved woman, who was owned by the reverend, confessed and later accused other women of witchcraft. She remained in jail until she was sold. The poor woman professed her innocence, but was convicted and executed. What followed was a cycle of accusation and confession. The accused either admitted to witchcraft and repented or they faced execution. In the end, fourteen women and five men were executed by hanging for witchcraft, one man died being pressed for a confession, and at least five others died in jail, one of those being the older scorned woman initially accused. She refused to confess to witchcraft herself or to accuse others.

Why was this older women scorned? What made her a target from others in her community? Besides refusing to obey the patriarchal rules to hand her dead husband’s fortune to his sons, she was considered by her Puritan neighbors to be promiscuous for having sexual relations out of wedlock. Agnes, Wanda’s nosy neighbor, isn’t a direct parallel, but her portrayal in the isolated town of Westview has many similarities to scorned women accused in the witch trials, where women resistant to patriarchal and Puritanical rules were singled out and murdered. Agnes is never seen with her husband. She flaunts her sexuality openly. She drinks in public. Within group settings, such as the Westview children’s benefit, she sits apart from the others in her community.

On a metatextual level, “Breaking the Fourth Wall” is a witch trial. Wanda, deep in depression, is pressed by her sons first to fix things, but she can’t. The twins ask about their uncle; Wanda insists that he is not their uncle, but is left with her own puzzlement about who he actually is. Monica Rambeau pushes her way back into Westview, confronts Wanda about her grief, and provides crucial information that SWORD is not responsible for Pietro. “Don’t let [Hayward] make you the villain,” Monica warns her; in reply, Wanda posits that maybe she already is. Yet this isn’t the truth Wanda wants to accept. She wants to have a villain in her story, someone to blame for the depressed, hopeless state she finds herself in, someone who brought the troublesome alternate Pietro to her life. Immediately preceding the confrontation with Monica, Agnes offers to take the twins and tries to show her mole. This moment is ripped straight from witch trials history, where women’s bodies were searched for signs of the devil, anything from a mole and skin tags to a birthmark or skin disease could be used as evidence. So it’s critical to ask: is Agnes the villain of Wanda’s story, or is that the answer Wanda needed? Did Wanda play right into the witch trial trope of accusing another women to avoid convicting herself of villainy? Admittedly, the intriguing thing about WandaVision is that at this point the answer could go either way for whether Agnes is Wanda’s evil nemesis or guiding mentor.

But let’s look at a few specific clues that suggest the audience is participating in metatextual mass hysteria regarding Agatha Harkness. In the Halloween episode opening credits, Agnes is seen with the boys with a quick shot of the word “Naughty” splashed across her sweatpants. Naughty typically refers to disobedient, and the definition in dictionaries attributes it generally to children. Informally it can mean mildly rude or indecent when it conveys an insinuation of sex. It doesn’t mean evil, but closer to the way one might suggest she is a scorned woman. The Halloween Spooktacular introductory credits sets up that Agnes has a relationship with the twins, yet she doesn’t interact with them in the context of the episode itself.

The burning question is, what happened to the twins once they went to Agatha’s house? The answer more likely lies in Wanda. She opens the episode “Breaking the Fourth Wall” by declaring her staycation. The broadcast signal is off-line. The twins ask for help with their glitching game and then Billy says he isn’t feeling well. Both times she brushes them off. Downstairs, Wanda is more concerned about her breakfast than her children. The milk that transitions from almond milk to whole milk is a reflection of Wanda’s id giving her what she wants. In some versions of the comics lore, Wanda’s children disappear when she isn’t focusing on them. We never see Agnes neglect the twins, but we do see Wanda turn her backs on them repeatedly. It could be Agatha ate them, as also happens in one comics tale, or it could be Wanda is a depressed person scapegoating her troubles on Agatha.

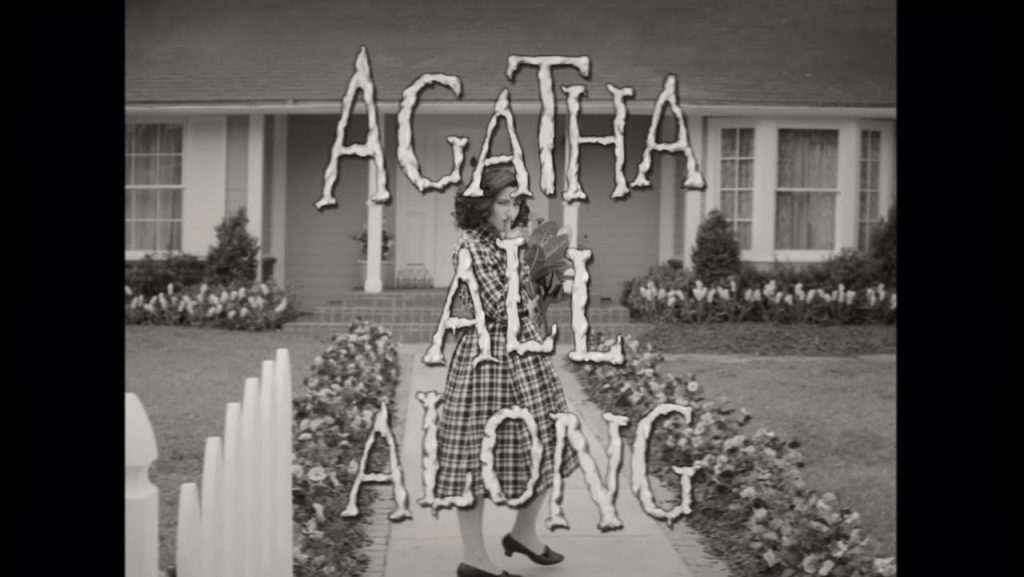

The boppy anthem “Agatha All Along” that closes out WandaVision’s seventh episode seems to punctuate the answer to Wanda’s question (and potentially hype the mass hysteria) about who is responsible for her current sad predicament as it rewinds through the events of the previous episodes. Kristen Anderson-Lopez, the lyricist behind the catchy theme songs accompanying each episode, shared on Twitter a Youtube video by Artsy Omni that breaks down the leitmotif of the WandaVision episodic themes. Anderson-Lopez says, “If you are wondering why you were so ready for the last song, it’s because, you were hearing the same song week after week.” So if we’re hearing the same song every week, have they all been Agatha’s songs or is this one still Wanda’s fiction?

In context, though, most of those previous events are not anything more than “naughty” as they run chronologically. Even the music is playfully spooky in the vein of The Munsters, a satire of monster movies and the wholesome sitcoms. In the fifties, Agatha comes on scene in her witch’s attire and changes to more era-appropriate garb, house plant in hand, and winks saucily. In the sixties, we see her rabbit Mister Scratchy loose and Agatha sitting alone at a table like a scorned woman casting some purple magic. For the seventies, she taps her purple magic on Herb’s shoulder after he’s cut through the brick wall. She is exercising some magic as Pietro arrives in the eighties, checking her lipstick in the rearview mirror when Vision catches up to her in the aughts episode, and sitting in the production chair during Wanda’s mockumentary interview in the current episode. In all of those instances, she plays naughty to the camera, not evil.

But Agatha admits she killed Sparky! In a Twitter conversion where I pondered how to interpret “Agatha All Along,” @joseyfish made a great point about the Sparky admission: “It’s tacked-on at the end of the segment, as if Wanda realizes that the montage doesn’t really paint Agatha as evil and tries to remedy that.” She also points out that the “I killed Sparky” declaration could be reframing the truth that Sparky ate Agnes’s plant, something that might have been allowed to happen within the Hex because Wanda didn’t want the dog.” The first quote wasn’t something I had thought about at that point, but the latter, regarding Wanda’s subliminal wants was definitely on my mind. If we’re looking at a character dealing with the trauma of loss, eliminating a potential bond early by getting rid of Sparky quickly, might actually be an emotional defense mechanism manifesting.

For now, I’m inclined to trust showrunner Jac Schaeffer when she notes that Wanda’s agency is critical to telling her story, which means agency in making good and bad decisions, like framing fellow witches as the big bad with only circumstantial evidence. I also believe we can look to recent Disney movies and television series that resonate with audiences to support the notion that Wanda and Agatha aren’t meant to work in opposition. Although Frozen series witch Elsa doesn’t have a rival, she is accused of witchcraft and hunted. She finds her powers in the first movie and faces no true foe in the second movie, in which she realizes her fullest potential in a quest for the truth of who she is. In Maleficent: Mistress of Evil, Maleficent assumes her role as leader of the Dark Fey to save her kind and find peace with the humans. In the Descendants series, witches Mal and Uma ultimately learn to work together to unite their kingdom. All of these journeys are internal stories of self-discovery and finding a path in times of societal upheaval. On a meta-textual level, in a tale about witches, falling into the traps of the witch trial, particularly ascribing the circumstances to other women or “the devil that made me do it,” doesn’t seem nearly as fresh of a take as what WandaVision has given us thus far.

- Hyperspace Theories: Bad Luck Ghorman - June 2, 2025

- Hyperspace Theories: One Year Later as ANDOR Kicks Off Season Two - May 15, 2025

- REVIEW: Tales of the Underworld - May 4, 2025