Steampunk and the Heroine’s Journey: Part Two

The surprising impact of Steampunk novels on The Heroine’s Journey

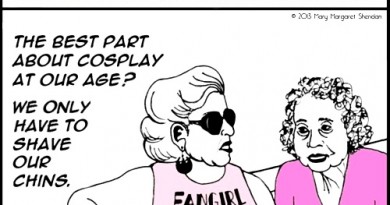

A series by Mary Sheridan

PART 2 – STEAMPUNK INFLUENCES: You may not realize that you have been Punk’d

.

“There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Author, Sherlock Holmes

.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a prolific writer. He wrote sixty Sherlock Holmes stories alone, the first in 1887 and the last in 1927. Since Sir Arthur’s lifetime, his Holmes’ character has been copied, borrowed, rewritten, revisited, and retold in print and on film by countless writers, and each time, the brilliant investigator was reinvented. Today, so many variations exist that it would be necessary to revisit the first Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, in order to know the character as Conan Doyle intended him.

During the past decade, Mr. Holmes has frequently been written into Steampunk novels and films. Anyone who only knows the character from these recent versions could mistakenly believe that the original Victorian novels were Steampunk.

The greatest Victorian Science Fiction minds – including Jules Verne, Mary Shelley, H. G. Wells, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – are often cited as “Steampunk authors.” Certainly, each penned outstanding stories, but in fact, their Victorian novels seeded the development of contemporary Steampunk. There are those who will argue this distinction, maintaining that Victorian Science Fiction and Steampunk are synonymous, yet history clearly shows that Victorian novels were instead the inspiration behind Steampunk fiction – not the first books of this Science Fiction and Fantasy subgenre.

Part I of this series investigated the complexities of defining Steampunk. Rather than restricting the these books to a dictionary entry, Steampunk was differentiated from its closest relatives, Science Fiction and Fantasy, by outlining its most unique qualities: Victorian era esthetics, altered history and/or time, steam-powered mechanization, and some degree of romance. The term speculative seems too obvious to be necessary.

Armed with that understanding, a closer look at the origin of the name “Steampunk”, as well as the first novel that was published in the newly-named subgenre, will illustrate that there is an important distinction between Victorian fiction and Steampunk novels.

HOW STEAMPUNK GOT ITS NAME

Documentation from 1979 shows that author K. W. Jeter wanted his newly-completed novel to stand apart from other submissions in the competitive Science Fiction market. He knew that there was a growing subgenre with common elements that deserved to carve its own niche. Jeter borrowed the word “steam” from the main power source in the Victorian era books. He then combined that term with “punk” from Cyberpunk – a similar subgenre of science-and-fantasy novels filled with youthful rebellion, which was an attitude that also seemed to fit the atmosphere of steam-and-clockwork novels. Critic Jeff Nevins feels that Jeter’s use of “punk” was accurate: “Steampunk, like all good punk, rebels against the system it portrays.” Brian J. Robb further suggests that some consider Steampunk to be “a collision between the science fiction genres of alternative history and Cyberpunk.”

Jeter suggested to his book’s publisher that it was time for this growing catalogue of extraordinary Victorian fiction to be recognized as unique, similar to the status that Cyberpunk was achieving. It seems that the publisher agreed, because the name stuck.

The book that Jeter submitted was Morlock Night. It became the first novel to be named in the new subgenre and remains a very good example of Steampunk.

For anyone who would like to understand just how the improbable aspects of Steampunk can work together, Morlock Night is an interesting, informative read. Picking up where H. G. Wells’ famous novel The Time Machine ended, the story mixes Victorian characters with other improbable historical figures and speculative situations such as King Arthur, Merlin, and the lost city of Atlantis. Jeter gave the spirit of Wells’ original story a more modern feel, altered its natural timeline, added characters, and balanced frightening battles with broad adventure and quiet moments of revelation. Morlock Night easily matches our established description of Steampunk. If you have read The Time Machine or seen its movie adaptation (1960 version recommended), or even if you follow The Big Bang Theory on television, you will recognize and be intrigued by this book’s title alone.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN VICTORIAN FICTION AND STEAMPUNK

Wells’ 1895 book is generally considered Science Fiction, and it is widely credited for the popularization of time travel throughout 20th century novels, comics, and films. However, Wells’ story includes only some of the basic elements of Steampunk. First, The Time Machine is consistently anchored in the Victorian era. It begins and returns to the same year – a point in time during which Wells lived and wrote. Despite its title, time travel remains shrouded in mystery, without answers. The second difference is that Wells does not try to change history; he embellishes it, using his knowledge of Victorian ingenuity, and he imagines where the industrialization might lead.

Perhaps the most telling enigma is the time machine itself, neither understood nor legitimized by the peers of Wells’ protagonist. If this was Steampunk, the machine would unquestionably exist as an accepted and natural part of an environment filled with fantastical inventions. Therefore The Time Machine novel is not Steampunk, but it was the prequel book to the first official “Steampunk” novel, Morlock Night (and a few earlier, independent Science Fiction “sequels”). Ultimately, Wells’ novel was a leading inspiration for a new class of fiction that the great author himself could not have imagined would emerge throughout the 20th century.

Many other works, such as War of the Worlds; 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea; Frankenstein; and From the Earth to the Moon, are also cited as seminal Steampunk novels, yet like The Time Machine, they are more accurately described as Victorian Science Fiction, Horror, Mystery, or Adventure. If we consider that the existence of all the core elements establishes a book as Steampunk, then again we note that these contain at least one but not all. They are incredibly influential, but they are Victorian foundation novels, the primary inspirations for decades of books that would eventually become a Science Fiction subgenre named Steampunk.

Contemporary writers often add to the Steampunk core framework by retelling all types of classic stories. One excellent example is the first book in author Marissa Meyers’ Lunar Chronicles series: Cinder, an outstanding, imaginative take on Cinderella. Meyers’ writes a futuristic dystopian Steampunk story that addresses current issues like cultural diversity, the reach of technology, medical ethics, social rejection, and generational division. It is significant to note that a reader’s knowledge of the original Cinderella is unlikely to interfere with their enjoyment of this new vision. While the key plot points remain intact, Cinder transports you to a different place and time in the fantastical manner that earned Steampunk its wings.

STEAMING THROUGH THE 20th CENTURY

We have established that Victorian Science Fiction heavily influenced the development of Steampunk, and the difference is often expressed by labelling recent novels “modern” or “contemporary” as opposed to the century-old “Victorian.” During the sixty-to-seventy years between most of the Victorian foundation novels and the 1979 naming of the Steampunk subgenre, storytelling changed under a variety of pressures.

As contentious as the subgenre’s identity is, it was not the only conflict that factored into the development of Steampunk fiction. Stories tend to reflect the times in which they are written, and so it is that the development of 20th century Science Fiction and its modern branches reflects the transformational rollercoaster that the world was riding.

At the end of Queen Victoria’s reign in 1901, the Industrial Revolution was well underway, and obviously, in real life it did not stop with the steam engine. Civilization was moving quickly into a new age of mechanization yet no one realized that in less than fifteen years, World War I would change everything.

The pendulum of war-driven economies swung back and forth for the next three decades. Men fought in two World Wars and many other conflicts as well. Women filled gaps in the workforce left by newly-minted soldiers according to shifting pre-war, wartime, and post-war needs. People sought harmless escape through decades of real life horror, and for those who retreated into books, imagining life in the Victorian era represented stability that was often lacking in their everyday lives.

Many decades also witnessed tremendous struggle for social change; repeated social, geographical, political, and economic crises led to the widespread paranoia and fear of the 1950’s Cold War era. That was followed by the peace-loving hippie revolution of the 60’s, and other unique rebellious movements in the last decades of a century that redefined civilization more drastically and much faster than ever before.

Examples of the “real life-to-fiction connection” are plentiful. Early character types were often based on real people. In his informative book, Steampunk: An Illustrated History, Brian J. Robb notes that there was a real man behind the stereotypical “mad” scientist that appeared in a multitude of books, comics, and films. His name is quite familiar: Thomas Alva Edison.

In terms of societal impact, the “Space Race” in the 1940’s and 50’s created a fascination with life beyond Earth. Humanity’s reactions to rapidly-advancing science and the need for respite from deteriorating world politics changed both storytellers and their audience.

Near the end of the 40’s, the then-Soviet Union and the United States joined in a volatile “competition” when both wanted to be first to send the a human into space, and to the moon. Long before meaningful rockets were launched, the public’s imagination soared, and authors were not immune. Venus became a favorite Science Fiction location, often imagined as a lush, habitable planet perhaps symbolic of its mythical name, and as well, the proximity of Mars made that world seem to be a reachable goal. Eventually, scientists brought that speculation to an abrupt halt.

Leigh Brackett is a name familiar to Star Wars fans for her work on a very famous script. The Empire Strikes Back was her first job as a screenwriter, but Ms. Brackett’s long career writing Science Fiction spanned thirty years, from the 1940’s through the 70’s. Her work included many books and short stories detailing life on planets in our solar system – all based on the slim knowledge of the day. Some of them were 50’s Golden Age Science Fiction novels of the sort also written by Brackett’s contemporaries, Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke. However, the Golden Age ended when real science discovered that the “lush” planet of Venus and our “friendly neighbor” Mars were not as hospitable as everyone imagined.

Through the last half of the 20th century, authors feasted on each other’s work, their own imaginations, and their speculations were always in jeopardy, something that the massive expansion in scientific knowledge frequently debunked after stories were published.

Perhaps most remarkable effect happened when science progressed to a reversal point, when a “fiction-to-real life” trend began, and technology began to erase the line between fiction and reality. What was imagined throughout the first seventy years of 20th century genre fiction became part of everyday life. Among the better known examples are the many fictional Star Trek devices that led to real life technology. Recently, news sources including the Washington Times reported that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was actually possible with the medical community’s announcement that they could, in fact, perform human head transplantation. A somewhat more palatable idea was noted by The Huffington Post: physicists believe that time travel is not only possible, but already happening.

Authors inserted the most fantastical plot devices they could imagine into hundreds of thousands of 20th century Science Fiction stories. Victorian novels inspired many of them. History gave them a wild ride filled with expansion and change. Technological progress brought fiction to life, and everything seemed to happen at the speed of light. Perhaps the popularity of Steampunk became its own rebellion, an expression of people’s desire to slow down in the attractive environment of a Victorian era lifestyle, in order to avoid some of the chaos of modern socio-techno-overload. The circle of the last century seems to be complete, and may assure Steampunk’s continued existence, giving new meaning to “back to the future.”

PICKING UP STEAM

Steampunk fiction has itself become an inspiration for many different aspects of modern society. The novels and the culture have never been more popular worldwide. In January of 2013, Tor.com noticed that Steampunk was increasing in popularity and that it was capturing a lot of media attention for its wide-ranging appeal.

Literary agent Joanna Stampfel-Volpe was interviewed about her interest in acquiring Steampunk projects: “It’s not just magic with things appearing out of thin air, but it’s people inventing things – even if these steam-powered/clockwork run machines are ultimately too fantastical to ever actually exist in real life, it feels like…well, maybe they really can. That’s probably the kid in me wishing for that, but who cares, right? Stories are supposed to make you feel like anything’s possible!” Stampfel-Volpe also lamented that “not a lot of the subgenre comes [her] way.”

Handsome and functional Victorian costumes; steam-powered rockets to the moon; clockwork robots; adventuring with your friends into a hollow earth; outrunning airship pirates; or lifting off to the outer limits of the universe: nothing is impossible in Steampunk. It seems that readers and members of the worldwide Steampunk community want to believe in the impossible: that perhaps, one day, they might build a real spaceship in their yard from spare clock parts and a steam engine. It was no different for Victorian novelists except that they did not have the chance to watch their dreams come to fruition. Walt Disney tapped into this same psychology when he opened the original Disneyland in 1955, based in part on his philosophy of making dreams come true.

“…Imagination has no age.

And dreams are forever.”

~ Walt Disney

WE HAVE ALL BEEN STEAMPUNKED: CONNECTING HISTORICAL DOTS

The following is a far-from-comprehensive list of 20th century novels, comics, films, and television shows that are linked to the development of Steampunk. Among them you will probably find familiar authors and influences, perhaps some that you were not aware had connections with this subgenre – until today. Hopefully, there are a few titles or names that will increase your awareness of the relationships among real history, the “foundation” Victorian novels, Science Fiction, and the advent and importance of the speculative stories that are embraced as Steampunk.

1880-2000

Oliver Twist — novel, Charles Dickens

Bleak House — novel, Charles Dickens

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz — novels, Frank Baum

The Invisible Man — novel, H. G. Wells

Dracula — novel, Bram Stoker

The Island of Dr. Moreau — novel, Mary Shelley

A Yankee in King Arthur’s Court — novel, Mark Twain

Edison’s Conquest of Mars — novel, G. P. Serviss

Pellucidar — novel, Edgar Rice Burroughs

Perelandra — novel, C. S. Lewis

The Difference Engine — novel, Gibson/Sterling

The Anubis Gates — novel, Tim Powers

Space 1999 — novel/television series, Stephen Baxter

The Ragged Astronauts — novel, Bob Shaw

Girl Genius — web/print comic, Phil and Kaja Foglio

Buck Rogers — film serials, Philip Francis Nowlan

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang — children’s book/film, Ian Fleming

The Wild Wild West — television series, Michael Garrison

Voyagers! — television series, James D. Parriot

The Adventures of Young Indiana Jones — television series, Jeffrey Boam / Carlton Cuse

The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. — television series, Jeffrey Boam / Carlton Cuse

Hellboy and Hellboy II — comics/films, Mike Mignola

City of the Lost Children — film, Marc Caro and Jean — Pierre Jeunet, directors

Watchmen — comic/film, Alan Moore

The Three Musketeers — film (2011), Guy Ritchie, director

Warehouse 13 — television series, Jack Kenny

Gotham by Gaslight — comic, Augustyn / Mignola / Russell / Barreto

Around the World Under the Sea — original story, Hayao Miayzaki

Spirited Away — animation, Hayao Miayzaki

Steamboy — animation, Katsuhiro Otomo

NEXT UP:

PART 3

DIVERSITY IN STEAMPUNK

Exploring issues of diversity and acceptance in Steampunk.

Mary Sheridan is a former ER and Trauma nurse with a life-long passion for real and imagined adventure – usually on horseback. Her right-brain enjoys fangirling over genre books and films; her left brain has finally given up trying to bring order to that chaos. Star Wars has been her favorite alternate reality since 1977 but she also enjoys Star Trek, The Hunger Games – most things creative and adventurous. Recently she has grown suspicious that a subliminal indoctrination process was initiated during her early years by a nefarious group of time-traveling operatives in Queen Victoria’s most Secret Service. While researching this series, Mary felt a sudden compulsion to join her local Steampunk Society and spends large amounts of time seeking period costume pieces – evidence of a latent desire to identify herself as a Steampunk. She is being monitored for disorientation since declaring that once she finds the perfect pair of brass goggles, she hopes to go back to the retro-future in a steam-powered DeLorean.

- Oscars: Free Us Or Die - February 23, 2015

- SAGA Read Along: Inspiring Characters - February 7, 2015

- Is There A Star Wars Gene? - January 13, 2015