Rey Deserved Better: The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 1

From its earliest incarnations, in the ideas generated by George Lucas and the blue sky imaginings of J.J. Abrams and the movie-making team, the Sequel Trilogy had at its core the origin story of a female Jedi. The Force Awakens delivered on this premise by centering Rey as the driving vector of the story, like Luke Skywalker in A New Hope, and delivering a climax in which she took up the Skywalker legacy lightsaber to face down the villainous Kylo Ren. The Last Jedi diminished the focus on Rey somewhat, especially by sidelining her in the final act, but nonetheless maintained her role as the Jedi protagonist in the story. Given the poor track record of Star Wars movies with the core heroines in their third films – objectifying Leia in Return of the Jedi and reducing Padmé to a weeping homebody in Revenge of the Sith – fans rightfully worried from the start whether the Sequel Trilogy would do better for Rey in her trilogy.

In the end, how did The Rise of Skywalker handle its treatment of Rey? Well, it could have been worse. Rey is the hero. She wins the day in the moment – mostly due to her own strength and fortitude. She is the future: a thousand generations of the Jedi live on through her – a destiny and legacy that she, like Luke or Anakin, does not have to share. She defeats evil, conquers her own fears, and gets her happy ending.

And yet… The Rise of Skywalker denies Rey the same caliber of agency in her third film that Luke and Anakin received in theirs. The film struggles to give coherent and consistent motivations to Rey for her actions and choices over the course of the plot, including with the redemption of Ben Solo. And the movie’s surprise twist, her heritage as the granddaughter of the diabolical Emperor Palpatine, carries far less emotional weight than it might have been given.

Ultimately, then, The Rise of Skywalker is neither a complete success nor a complete failure for Rey’s character. Yes, it could have been worse – but it also could have been far better.

Concluding the Hero’s Journey for Rey

Like the two prior trilogies in the Skywalker saga, the Sequel Trilogy builds its Jedi protagonist’s arc upon the Hero’s Journey framework of storytelling. The Force Awakens is Rey’s origin story; The Last Jedi passes the baton from Luke to Rey as the singular heir to the spiritual legacy. In The Rise of Skywalker, Rey finishes her heroic cycle – still the same optimistic scavenger we first met on Jakku, but also forever changed by her journey. In a separate post we analyze in detail this third phase of the Hero’s Journey for Rey, especially how it follows the resolution of Joseph Campbell’s monomyth by showing Rey synthesize her past as a scavenger and her destiny as a Jedi into a new path combining the best of both.

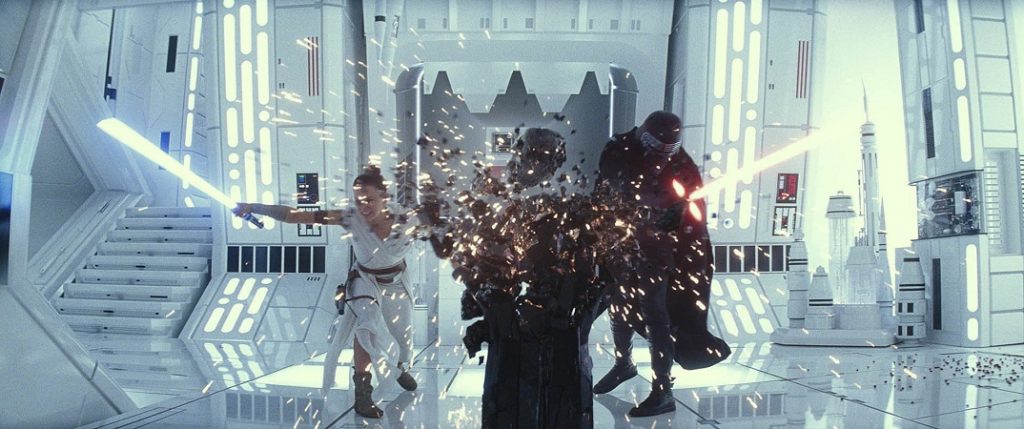

Rey’s arc in The Rise of Skywalker has aspects that are worthy of praise. Though only briefly due to the passing of Carrie Fisher, we do get to see Rey training as a Jedi with Leia as her Master. Rey undertakes a banter-filled quest with her friends in the Resistance – Finn, Poe, Chewie, Threepio, and BB-8 – from Pasaana to Kijimi to Kef Bir. She has her final showdown with her trilogy nemesis, Kylo Ren, on the wreckage of the Death Star, followed by her final showdown with her own worst fear – “myself” – with reassurance in the form of kindly words from ghostly Luke Skywalker on Ahch-To. The young woman who once cried tears for her feelings of abandonment on Jakku now stands tall in front of her grandfather to declare, “My parents were strong. They saved me from you.” Then she brings to culmination the legacy of a thousand generations, the last Jedi defeating the last Sith by standing firm in the light side of the Force. Symbolizing her personal as well as spiritual achievement, Rey renounces her connection to Palpatine, one only of genes, and chooses to be a Skywalker, part of her found family.

At the same time, now that it has come to a close, it is worth noting what Rey’s journey is not. In contrast to the stories of her prominent female lead contemporaries, Star Wars did not provide Rey with a Heroine’s Journey. While Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Gameswas framed by Suzanne Collins as a nurturing hero, Rey is principally a conquering hero, especially with Kylo Ren and Palpatine in The Rise of Skywalker. Unlike Diana in the 2017 Wonder Woman film, little if anything in Rey’s journey hinges on her overcoming barriers or expectations based on her sex or gender. Though she shares the theme of a search for identity with Carol in the 2019 Captain Marvel movie, Rey’s power is unlocked, developed, and explained on screen almost entirely through her interactions with men – Kylo Ren, Luke Skywalker, Supreme Leader Snoke, and Palpatine, with only a few minutes shared with Leia – rather than from the strength of her female friends and mentors, and within herself. Ironically, for one brief moment on Kef Bir she undertakes the task of literally “healing the wounded masculine,” but without any of the meaning or significance attributed to that concept in the writing of Maureen Murdock. In The Rise of Skywalker, Rey is not synthesizing the feminine and masculine sides of herself or the influences of those factors upon her life, as in Murdock, but rather synthesizing the ordinary world of a scavenger and the extraordinary world of a Jedi, as in Campbell. Relying on Campbell’s model remains true to the history of Star Wars, of course – but it does nothing new or different to mark out the path forward into the franchise’s future.

Rey’s Diminished Agency

Another notable contrast exists between Rey in The Rise of Skywalker compared to Luke in Return of the Jedi and Anakin in Revenge of the Sith, the capstone movies to their respective trilogies. Unlike the two men, Rey has considerably diminished agency in shaping her own fate over the course of the film.

Data from the film industry has proven not only that women exist in significantly fewer roles, but also that female characters tend to be written much more passively than men. This reality plays out in The Rise of Skywalker, in which Rey is often passive or reactive as the story unfolds. Poe tells her she needs to join then fight, and she acts on his assessment upon learning the news about Palpatine. She goes to Pasaana following Luke’s notes; she finds Ochi’s ship with directions from Lando; she tags along to Kijimi because Poe knows Babu Frik; the translation from the dagger leads her to Kef Bir. She reaches for the First Order transport to save Chewie from captivity, and loses her temper in reaction to the intervention of Kylo Ren. She draws her lightsaber against Kylo Ren on three occasions, each time because he pursued her to another location – the desert of Pasaana, the streets of Kijimi, and the wreckage of the Death Star – to try to turn her to dark side. She goes to Exegol because she has no choice; Palpatine will not come to her, so she must go to him. And she defeats him because the spirits of Jedi past speak to her and inspire her to rise, not because she has the strength and bravery to rise solely on her own. It is important to note that any particular choice to show a protagonist as reactive rather than proactive in any given story is not necessarily flawed or undermining. In the aggregate, however, the script for The Rise of Skywalker written by two men leans into the trope that women exist and men do.

Even Rey’s moments of agency are inspired by someone else. When she uncovers Luke’s notes about the wayfinder and clues to its location, she insists to Leia that she must undertake the mission; refuting Leia’s simple “No.” – constrained by the previously filmed scenes with Carrie Fisher – Rey responds, “It’s what you would do.” After the revelation of her heritage and the fateful duel on Kef Bir, Rey absconds in Kylo Ren’s TIE fighter and flies to Ahch-To, where she sets the starship ablaze and declares her intention to remain there forever, as Luke did. (Only to be immediately chastised, by Luke, that he had been mistaken in doing so.)

This marks a sharp contrast with Luke in Return of the Jedi. In that movie, his choices drive the story: he plans and executes the mission to rescue Han from Jabba’s palace; he returns to Dagobah to keep his promise to Yoda; he volunteers to join the Endor strike team; he leaves the team and surrenders to Vader to try to reach the good in his father. While the Emperor successfully instigates Luke to draw his weapon, Luke’s triumph comes not from external aid but from his own courage to throw aside his saber and reject the dark side.

Although Anakin’s path in Revenge of the Sith is more reactive – the core conceit of his tragedy is that his emotional weaknesses are being exploited by Palpatine’s manipulations the whole time – he is not a passive participant in an adventure driven by others. He rescues Obi-Wan from the buzz droids, then again on the Invisible Hand after the death of Dooku; he seeks Yoda’s guidance about his nightmare, then chooses to keep his fears a secret from Obi-Wan and the other Jedi; he disobeys orders and intervenes in Mace Windu’s confrontation with the Chancellor. Above all, he chooses to join the dark side and become a Sith because he hopes it will bring him the power to save Padmé. Although Darth Sidious engineers some of these opportunities, at each step Anakin has a choice, and makes it.

The plot of The Rise of Skywalker is frenetic, especially in the first two hours. Surely, however, more room could have been created for Rey’s agency. Like Luke and Anakin before her, Rey should been the driving agent and propulsive vector in the third movie of her story.

Rey’s Inexplicable Motivations

It is bad enough that too much of Rey’s story in The Rise of Skywalker deprives her of agency, but those flaws are compounded by the movie’s failure to provide her with sensible and comprehensible motivations for the actions she takes. This results in the impression that Rey does things because the writers decided she needed to do them to fit their intended outcome – not because they actually make sense for what Rey as a character would do.

On Ajan Kloss, for example, Rey is portrayed as proudly training as a Jedi with Leia as her Master – but also keeping secrets from her. As she prepares to depart for Pasaana, Rey says, “There’s so much I want to tell you,” to which Leia replies, “Tell me when you get back.” Out of universe, we know that this dialogue was concocted as a way to use a previously filmed line delivery by Carrie Fisher in this movie. In universe, though, it makes no sense. One of Rey’s important lessons in The Last Jedi was that lack of open and candid communication, in both the past and the present, is a mistake that can have tragic, or nearly tragic, consequences – especially between Jedi pupils and masters. Elsewhere in The Rise of Skywalker, both Rey and Luke are shown having learned from the mistakes explored in the previous film. In that context, Rey’s secret-keeping from Leia is inconsistent and unexplained. In the earnest objective of repurposing Carrie Fisher’s unused scenes, the writersundercut Rey’s characterization.

Similarly, it is nostalgia and intertextual connectivity, rather than Rey’s own motivations, that explain why Rey travels to Ahch-To after Kef Bir. Just as Luke returns to Yoda briefly in Return of the Jedi and receives confirmation of Vader’s revelation that he is Luke’s father, so too Rey must briefly revisit Luke in The Rise of Skywalker to receive confirmation of Kylo Ren’s revelation that Palpatine is her grandfather. It also allows Luke to reaffirm that his fatalistic exile was a mistake, one that Rey should not repeat – except that nothing in her motivations explains why she would have chosen to do so in the first place. Unlike Luke, she did not think the Jedi should end: she read the ancient texts and trained with Leia. Why would she suddenly abandon that path? Unlike Luke, who left behind a New Republic and relative peace and stability in the galaxy when he went into exile, Rey knows without a doubt that the First Order and Sith fleets are poised for imminent conquest if Palpatine is not defeated. She would not only be letting the Jedi die out, but also dooming all her friends to annihilation and the entire galaxy to another reign of tyranny. Why would she simply give up and accept that outcome? It makes no sense with anything we have seen from her character previously, and this pretext is so flimsy that Luke barely has to cajole Rey into reversing her decision and heading for Exegol. But apparently the writers wanted Rey to mirror Luke in a literal and overt manner before their conversation about her impending confrontation with Palpatine – and to be flying Red Five for nostalgia value, too.

Perhaps we are meant to think that Rey’s motivations come from her fear that she will fall to the dark side. Fear that her vision of the Sith throne will come true, just like her youthful visions of the Ahch-To island came true; fear of the Force lightning she unleashed on Pasaana; fear that her grandfather’s bloodline will dominate her destiny. Except that, by the time Rey has reached Ahch-To, The Rise of Skywalker has gone out of its way to reaffirm that Rey is a good person – and that she knows it. She heals the vexis, which gives her a multi-eyed blink of serpent gratitude before slithering away. Zorii Bliss deems her heroic and worth helping. Rey oils up D-O’s squeaky wheel, and he calls her “very kind.” Rey is the first character in Star Wars to request Threepio’s assessment of the odds, and treat it with respect. Even before Luke Skywalker explicitly reaffirms the goodness in her heart, the movie has repeatedly shown the audience – and Rey – that she is compassionate and kind. And all of this, of course, builds on Rey’s characterization in The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi, which also repeatedly showed her good heart, sense of justice, and compassion. If fear of falling to the dark side was supposed to be her motivation for portions of The Rise of Skywalker, it is dissonant with her established characterization and accordingly unearned.

For the same reason, Rey’s established characterization does not explain what her motivation would have been for healing the mortal wound to Kylo Ren at Kef Bir. Though she shows kindness and compassion to those who deserve it, on the other hand she is never shown having qualms about fighting or defeating malicious and villainous adversaries. In The Force Awakens she beats up Unkar’s thugs, steals the Falcon from him, releases the rathtars upon two criminal gangs, blasts stormtroopers at Starkiller Base, and duels Kylo Ren in the forest. In The Last Jedi she chops down Praetorian Guards without hesitation and cheers her successful shots at the First Order TIEs from the Falcon’s cannons. In The Rise of Skywalker she again blasts stormtroopers on Pasaana and the Steadfast, draws her saber against Kylo Ren three times, and disintegrates Palpatine with his own power at Exegol. Moments before their duel begins at Kef Bir, Kylo Ren has destroyed the wayfinder, taunted Rey about her bloodline, and again tried to convince her that her only future lies with the dark side. His lightsaber attacks on her are unrelenting, pounding her to her knees. When an opening emerges, she does not hesitate for a second to take it, stabbing him through the abdomen with his own blade.

And then, inexplicably, she kneels down and heals the wound, saving the life of her nemesis for the past two-and-a-half movies. Is it because she regrets her own action, feeling it was motivated by revenge or anger rather than justice or righteousness? Is it because she mourns for Leia, and believes Leia would have wanted to spare her son? Is it because she believes Kylo Ren has already returned to the light to become Ben Solo, even though his memories of his father and decision to honor what his mother fought for has not yet occurred? Or is it because she senses that Kylo Ren might still choose the light, though he not yet actually done so, and believes that healing him in an act of compassion might accelerate him making the right choice? It is possible to conceive of a variety of explanations – but none of them are actually given in the movie. Rey has only one line of dialogue afterward at Kef Bir, and it implies that she still views the man she healed as Kylo Ren: she would have taken Ben’s hand, she says, but she does not take his hand now, instead leaving him alone on the wreckage while she steals his TIE fighter to leave him behind. And then she says nothing at all on the matter to Luke when they speak at Ahch-To.

Again Rey’s actions have been compelled to fit the plot, rather than motivations that make sense for her character. The writers wanted Ben to join her at Exegol, so he needed to survive Kef Bir. Existing lore certainly provided a means to do so: Maul, Vader, and Palpatine all used their dark side rage to stave off death and endure. The problem with that power, though, is that it would be Kylo Ren, not Ben Solo, arriving at Exegol to stand beside Rey. That would have provided its own fascinating dynamic to the showdown, but it is not the one the writers were interested in telling. In addition, The Rise of Skywalker on its own terms provided another means to save Ben: if Leia can project her consciousness across the galaxy to speak to her son, surely she could also use the Force to repair his wound at the same time, too. That way Ben’s redemption and survival would come from the unconditional love of his mother, an entirely understandable motivation. Instead, Rey is tasked with sparing the life of her nemesis – before he has shown he is redeemed – because the plot requires it.

Another interpretation, favored by some fans, is also possible: that Rey is motivated to heal him not by guilt or compassion, but love. In this interpretation, Rey said she wanted to take Ben’s hand, and then kissed him at Exegol, because she has fallen in love with him over the course of the three films.

But this interpretation of Rey’s motivation, like the corresponding interpretations of The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi made in the years preceding The Rise of Skywalker, is profoundly troubling and problematic for the message it sends about romance and romantic story arcs. In The Force Awakens Kylo Ren chases Rey through the Force, immobilizes her and penetrates her mind before knocking her unconscious, abducts her limp body, imprisons her in an interrogation chair in a detention block cell, again forcibly intrudes into her mind without her consent (“You know I can take anything I want.”), murders his father in front of her, propels Rey into a tree, attempts to murder her best friend, and tries for the first time to ally her with the dark side. In The Last Jedi Kylo Ren tries to mind-trick her into revealing the location of Luke Skywalker, deceives her about the night he destroyed Luke’s training temple, agrees with her accusation that he is a monster, disrespects her autonomy by refusing to cover himself when she expresses discomfort at his shirtless appearance, deliberately exploits her youth as impoverished orphan to attack her self-confidence and position himself as the only person who cares about her, and again seeks to lure her to the dark side. Rey believes that when they touched hands she saw him reject the dark side, but he makes absolutely clear in the Supremacy throne room and at Crait that he has no such intention. In The Rise of Skywalker, he repeatedly intrudes into her mind without her consent, expresses his intention to not give up stalking her, continues taunting her about his additional knowledge of her family heritage even after her tearful objection (“I don’t want this!”), and relentlessly pursues her from Pasaana to Kijimi to Kef Bir, where he again insists that she has no future except to join him on the dark side. These interactions display all the hallmarks of intimate partner abuse: gaslighting, negging, emotional manipulation, ignoring personal privacy, rejecting pleas to be left alone, unwanted surveillance, stalking, non-consensual intimacy, and even physical violence. If this is the kind of romantic story that Lucasfilm and Disney intended to portray, they will rightly bear a substantial negative reaction from many critics, commentators, and fans.

The movie would be best served with those two moments omitted: no remark about taking Ben’s hand and no kiss. But even with them included, that they are motivated by love is not the only required interpretation. In The Force Awakens, Rey and Finn share a series of dialogue about taking each other’s hands, and it did not culminate in a romance; earlier in The Rise of Skywalker, Rey took hands with Finn, Poe, and Threepio in solidarity of cause before heading to Kijimi. Rey similarly could take Ben Solo’s hand as an ally and fellow Jedi, without necessitating a romantic connotation. And even their kiss is unaccompanied by any dialogue expressly establishing its significance; it possible to view it as a gesture of gratitude, relief, and celebration rather than romantic affection. Perhaps the novelization of The Rise of Skywalker by Rae Carson or the junior novelization by Michael Kogge will shed light on what Lucasfilm intends as the official emotional state of these moments. Until then, Rey’s motivations toward Kylo Ren and Ben Solo remain inexplicable, too.

The Problems with Rey Palpatine

Shortly after the release of The Last Jedi, we published The Problems With Rey Random: A Storytelling Analysis to explain our evaluation of the decision seemingly made by the second film in the Sequel Trilogy. We considered the ramifications for the Rey’s character, the first two films in the trilogy, and the themes of the Skywalker saga as a whole – and, in combination with Rey At Risk Revisited: The Danger Signs from The Last Jedi, we emphasized our serious concerns about the potential implications of the choice for the concluding movie. Fortunately, the worst possibilities did not occur in The Rise of Skywalker: Rey is not sidelined for any major segment of the plot; Rey is not superseded by Ben Solo as the Jedi hero; Rey is not discarded as an interloper into the Skywalker story but rather adopted into it, becoming part of the family by name and by destiny.

On the other hand, the manner in which The Rise of Skywalker reversed the decision for Rey Random – by making her Rey Palpatine – only introduces a new and different set of problems. Most of all, they show that the narrative choice was unnecessary to make the conclusion of Rey’s story powerful and effective.

First, in a franchise that has long struggled with the ways its stories perpetuate patriarchy, this decision only adds fuel to the fire. Rey’s father is the Emperor’s son, we are told in the movie – apparently so that her name is Palpatine, too. Except that later, when Palpatine flings the weakened Ben Solo into the chasm, he specifically declares in his monologue that he is taking revenge against a “Skywalker,” which is not the name used by Leia or her son. By the movie’s own logic, then, Rey would have been a “Palpatine” through her mother’s line regardless. Or perhaps the writers simply were fond of the dichotomy of Vader’s daughter and the Emperor’s son to invert the dichotomy of Kylo Ren and Rey, and failed to recognize the connotation.

Second, no bloodline connection to Palpatine is needed for Rey’s greatest fear – “myself” – to ground her characterization. In The Force Awakens, Rey is shown with a willingness to fight, to stand up to bullies, to act aggressively. Though she is written as more subdued for much of The Last Jedi, she still engages in saber training, attacks Luke in the rain, fights the Praetorian Guards on the Supremacy, and cheers while blasting TIEs from the Falcon on Crait. In the first half of The Rise of Skywalker she releases a burst of Force lightning on Pasaana and engages in two vigorously and emotionally fraught lightsaber duels with Kylo Ren. As noted above, all three films establish that Rey is a good person, and it is not especially credible that the young woman who has repeatedly rejected Kylo Ren’s attempts across the trilogy to turn her to the dark side would have any real susceptibility to the manipulative words of the Emperor, either. On the other hand, the Skywalker saga, like all epic storytelling, has precedent for the idea that the higher the stakes, the easier it is to accept the ends justifying the means. Even good-hearted Rey might worry about the solidity of her own moral fortitude in the face of their desperation to stop Palpatine’s reconquest of the galaxy. Kylo Ren is correct to say that darkness is “in our nature” – but not because of his or her bloodline, but because it is part of human nature, in all of us.

Third, nothing in the found family dynamic of the story requires a Palpatine heritage for Rey, either. Certainly it has nothing to do with her bonds formed with Poe or Finn, Chewie or BB-8, Threepio or D-O. Likewise, the bonds she makes with Han, Luke, and Leia over three films also work fine on their own – as the fan reactions to them after The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi demonstrated. Perhaps the twist in The Rise of Skywalker creates a little extra zing to the ending: not only does Palpatine’s own kin defeat him, but she also repudiates him and takes the name of his despised nemeses. But the emotion of Rey finding her place with the family she chooses, and who chooses her in return, stands well enough on its own.

Fourth, by introducing the twist halfway through the third film in the trilogy, Rey’s Palpatine heritage is able to deploy only a fraction of the thematic resonance it might have carried. Dark can come from light (Kylo Ren from Ben Solo) and light can come from dark (Rey Skywalker from Rey Palpatine). Can we escape our heritage, our pasts, to chart our own course? When should we honor our family legacy, and when should we reject it? How much of our fate is set by history, or by destiny, and how much is determined by free will and the power to choose? These themes could have been powerful ones. With Rey ending up related to a legacy character anyway, these themes should have been the story of the third trilogy of the Skywalker family saga. (This would be equally true, it is worth noting, if the third movie had revealed Rey to be Luke’s daughter or Kylo Ren’s sister.) Instead, they are thrown in at the last minute, not earned beforehand and not rewardingly paid off afterward.

In the aggregate, the Rey Palpatine reveal adds little benefit to the story or her characterization, while bringing considerable downside. Some view it as a part of a broader rejection of The Last Jedi. Others prefer the thematic and emotional power of Rey “no one” rather than reinforcing patriarchal lineage. Another view is that it reinvents the entire saga and diminishes the Skywalkers (to be discussed further in an upcoming post). Regardless of one’s perspective, including those who find enjoyment or satisfaction in it, the Rey Palpatine reveal ultimately is most damaging because it distracts the focus from Rey herself, and the triumphant end of her story, and instead draws attention to her connections to other characters.

And it is this reality, in the end, which creates the lingering disappointment: Rey is a great character because she is Rey. That should have been enough.

Pingback:The Failures of The Rise of Skywalker, Part 6 – FANgirl Blog