A Few Thoughts on Last Week’s Star Wars Rebels: “The Forgotten Droid”

Last week I had the honor of joining RebelForce Radio Declassified, a roundtable devoted to Star Wars Rebels; we had a great discussion about the latest episode, “The Forgotten Droid.” Prior to that discussion I had live-tweeted the show during the East Coast viewing. Here are some of my thoughts, in no particular order.

Last week I had the honor of joining RebelForce Radio Declassified, a roundtable devoted to Star Wars Rebels; we had a great discussion about the latest episode, “The Forgotten Droid.” Prior to that discussion I had live-tweeted the show during the East Coast viewing. Here are some of my thoughts, in no particular order.

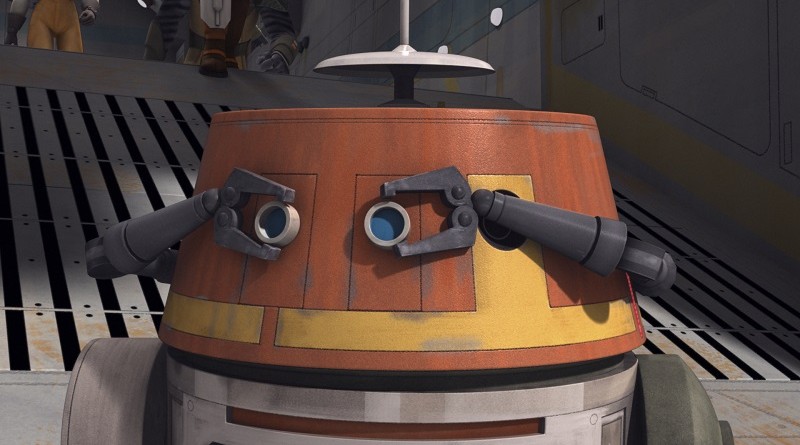

1) While it may be called “The Forgotten Droid,” the Chopper-centric episode doesn’t involve the Ghost crew’s plucky astromech being forgotten. Hera reveals she chose the needs of the fleet over Chopper, who had gone missing-in-action. Imperial inventory droid AP-5 is the droid befriended by Chopper and perhaps the one “found,” as in discovering a new purpose.

2) During and after the airing of the episode, fans on Twitter engaged in quite a bit of discussion about Chopper’s character development. The term is brought up again in the roundtable. Both times I disagreed with this assessment. The term “character development” can mean the act of creating – developing – the character before the storytelling begins or, once the story is underway, changing a character through unfolding events in the plot. For instance, in the previous week’s episode, “Shroud of Darkness,” Kanan undergoes his Jedi trial, a test that involves how he would react to the potential of Ezra’s fall, and is knighted. This is clearly a development in Kanan’s character arc.

In his episode, Chopper does his own thing, mucks up a mission, and makes a friend. None of these things are new to the character. While we hadn’t seen him bond with another droid, he had with Ezra during the first season, as well as the rest of the crew previously. Pandu E Poluan on Twitter got it right in labeling last week’s show as a “character exposition” episode, more like the Hera B-wing episode “Wings of the Master.” We learn a few new things about the droid, most importantly that he was rescued by Hera during the Clone Wars.

In his episode, Chopper does his own thing, mucks up a mission, and makes a friend. None of these things are new to the character. While we hadn’t seen him bond with another droid, he had with Ezra during the first season, as well as the rest of the crew previously. Pandu E Poluan on Twitter got it right in labeling last week’s show as a “character exposition” episode, more like the Hera B-wing episode “Wings of the Master.” We learn a few new things about the droid, most importantly that he was rescued by Hera during the Clone Wars.

3) The reaction to my thoughts on the 1’s and 0’s of droid logic was a bit frosty during the roundtable, but that won’t stop me from talking about it more. First, some background on my knowledge of robots, artificial intelligence, and programming. I have a Bachelor of Science in Engineering, and engineers learn programming as part of our undergraduate work. My area of expertise is traffic systems, which includes smart cars and adaptive signal systems that hopefully won’t become SKYNET. My novel Wynde incorporates several forms of artificial intelligence, in part inspired by the droids of Star Wars. As part of my worldbuilding process I have done quite a bit of research on artificial intelligence.

Back in 1977, the film Star Wars helped computer scientists both understand and see a way past the troublesome phenomenon called the “uncanny valley.” From the Smithsonian magazine:

The concept was first posed in 1970 by the Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori. He’d noticed that as robots grow more realistic, people’s attitudes toward them change. When a robot is toylike and capable of only simple, humanlike gestures, we find it cute. If it starts looking and acting a bit more human, we find it even more endearing. But if it gets too human—as with, say, a rubbery prosthetic hand—we suddenly shift allegiance. We find it creepy. Our emotional response plunges into what Mori called the uncanny valley.

Why would overly realistic robots so unsettle us? When they become nearly human, we start focusing on the things that are missing. We notice that the arms don’t quite move as smoothly as a real human’s, or the skin tone isn’t quite right. It stops looking like a person and starts looking like a zombie. Angela Tinwell, a professor specializing in video game design at the University of Bolton in Britain, suspects we unconsciously detect sociopathy or disease.

Mori saw a way out of this conundrum. The most engaging robot would be one that suggested human behavior, but didn’t try to perfectly emulate it. Our imaginations would do the rest, endowing it with a personality that we could relate to.

In essence, Mori perfectly predicted the appeal of R2-D2.

Chopper easily fits into this mold of a robot that engages, first encapsulated in Star Wars by R2-D2. In fact, anthropomorphizing non-human entities is a literary device as old as storytelling. The galaxy far far away, however, hasn’t created a storytelling universe where robots are sentient creatures, but rather situations that would make it credible for artificial intelligence to learn different behavior. I believe it’s important that we understand that a droid isn’t thinking in human terms because if we can’t understand a robot’s thoughts process, it’s impossible to make the leap to understanding any alien thought process. Then all the characters are anthropomorphized, even the alien ones. And to me, that creates a really boring galaxy.

In the episode we learn that Chopper originally served as an astromech on a Y-wing. His AI – for a quick primer on the topic and its definition check out Computer World – would be designed to work efficiently and intelligently to better serve his pilot; this adaptive programming is in essence his survival instinct and his purpose for existing. Once no longer serving in a Y-wing, Chopper must learn to adapt. As a robot he still requires repairs, power, and occasionally new legs. His base programming, though, tells Chopper that he must serve his pilot’s needs, and Hera fits that bill. Chopper learns to serve his pilot in many ways that are intelligent. He can navigate, shoot, and pilot if called upon. He can even communicate and learn new terms that aren’t in his vocabulary, like “friend.”

Think of Chopper as a child. When a child asks “What does it mean that grandma is dead?” most people offer a bunch of rather vague, non-tangible answers. If a child were to ask what a “friend” is, adults might offer up various thoughts on the concept that would be highly abstract to a droid, such as someone we love or feel affection for. But as a logical computer, Chopper could infer its meaning from how he sees friends act – that friendship implies making alliances or bonds for mutual benefit. Again, acquiring friends is something Chopper has been shown doing, and as pointed out in Rebels Recon, Chopper doesn’t have an arc through which he needs to develop.

4) While Chopper does give up his recently stolen replacement leg to repair his newfound friend AP-5, I don’t view this as a huge sacrifice. Chopper’s current leg works just fine. If he is adaptive and sees the survival of the Rebel cell as his best means to continue operating, giving up the aesthetically superior leg for parts to enable another droid to assist the cell is quite within the realm of reasonable droid logic, without the need to resort to an emotion-based decision. What all this demonstrates, though, is that even droids can move our emotions, as the audience of the story, when used correctly. In this episode, Chopper appeals to the sense of not fitting in or not being complete, and AP-5 is bullied and lost his usefulness. These are entirely relatable situations that the storytellers used to their advantage. Part of analyzing television shows is to understand when the story or characters manipulate our emotions to the show’s advantage and then being able to separate the two.

4) While Chopper does give up his recently stolen replacement leg to repair his newfound friend AP-5, I don’t view this as a huge sacrifice. Chopper’s current leg works just fine. If he is adaptive and sees the survival of the Rebel cell as his best means to continue operating, giving up the aesthetically superior leg for parts to enable another droid to assist the cell is quite within the realm of reasonable droid logic, without the need to resort to an emotion-based decision. What all this demonstrates, though, is that even droids can move our emotions, as the audience of the story, when used correctly. In this episode, Chopper appeals to the sense of not fitting in or not being complete, and AP-5 is bullied and lost his usefulness. These are entirely relatable situations that the storytellers used to their advantage. Part of analyzing television shows is to understand when the story or characters manipulate our emotions to the show’s advantage and then being able to separate the two.

5) Last week Johnamarie Macias noted she’d like to see more female stormtroopers in Star Wars Rebels. The same could be said for droids rounding out the equation. Of five new speaking characters – two stormtroopers, the Ugnaught, AP-5, and captain – they were all male. Star Wars is capable of doing better, and things like this could easily be caught while breaking episodes using the Geena Davis Two-Step guideline to making Hollywood less sexist.

6) Exposition or character-driven episodes are necessary beasts of serial storytelling – not every episode can have major moments of character development – and they tend to be the episodes that get the most varied reaction from the audience. Some really liked the B-wing episode for the use of the favorite starfighter; others felt it really didn’t deliver enough on Hera’s progression. I was ambivalent on the droid episode; others really like it. Earlier this year, we’ve seen character driven stories around Zeb and Agent Kallus expose more about the characters and develop them.

7) Why does it matter that we call it character exposition and not character development? For one, if simply learning something new is character development, then that’s all any episode is. But back to my point earlier, we only learn new factoids about Chopper. His ability to create friendships or alliances isn’t new to our understanding of his character. The term character development is used by storytellers to define specific moments, moments of change. At one time, the term Mary Sue had a very particular meaning. Then Rey came along in The Force Awakens and people, including a notable screenwriter, decided to hurl the word about in connection with a character in a way that used the term incorrectly. Sure, Mary Sues exist, but let’s call them for what they are and character development for what it is.

For more of my thoughts on “The Forgotten Droid,” check out this week’s episode of RebelForce Radio’s Declassified.

“The Forgotten Droid” features Chopper on his own as he gets separated from the crew of The Ghost and finds himself on an adventure. We break the whole episode down from start-to-finish with a great roundtable discussion featuring expert analysis from our esteemed panelists. Joining Jimmy Mac and STAR WARS artist Spencer Brinkerhoff III are Tricia Barr (Fangirls Going Rogue) and Geek Out Loud’s Steve Glosson.

- Ten Years of Hyperspace Theories - October 28, 2024

- Hyperspace Theories: The Heroine’s Journeys of the MCU’s Echo and What If? Series - August 29, 2024

- Hyperspace Theories: THE ACOLYTE and Star Wars Brand Management - August 7, 2024

I love this post! While I completely appreciate your take on droids and their programming (and there is no doubt that you know WAAAAY more about the subject of robotics than I do), I tend to think of droids in Star Wars as sentient beings.

Witness C-3PO talking to himself in A New Hope after he and R2 part ways in the desert. If 3PO relied solely on his programming, there would be no reason to talk to himself. This suggests that 3PO has self-awareness and theory of mind. He plans for the future and has wants and desires. I would argue that he has intrinsic value as well, beyond the value placed on him by organic sentient beings.

Even the battle droids in the Clone Wars seem to have feelings. One of my favorite B1 moments is in season 1, episode 1 when Yoda is destroying a battle droid and the droid laments, “But I just … got … promoted!” There would be no programming reason for that sort of vocalization, which makes me think that Star Wars droids (maybe not all, but a good portion) have sentience and a sense of self beyond what specific duties they’re programmed for.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. I know that the idea of sentient robots doesn’t really make sense in our world, but I always assumed that droids in the GFFA were technologically far beyond anything we could imagine.

Thanks for your thoughts. The uncanny valley phenomenon actually creates reasons for droids to be built with quirks and human-like vocalizations. If droids are sentient then even the Rebel Alliance engages in slavery. Sentience is a function of subjectivity and pretty much everything we see from the droids can be tied back to objective functions. It’s a fun topic to explore, especially what age we first meet the droids and how the storytellers in each moment did or didn’t think about the characterization/use of the droids.